By Michael Laramie

Friedrich Bangerter. The centrifugal gun was but one of 50 inventions the Swiss born engineer had to his credit. These ranged from automaton figures that could write the alphabet to early fire detection and alarm systems, to a futile act of defiance against the laws of thermodynamics with the Perpetual Motion Clock.

The Sound of Silence

Friedrich Bangerter peeked out from behind a curtain at the crowd gathering in his spacious Brooklyn loft. The Swiss native and mechanical engineer quickly categorized the observers who had begun chatting among themselves. There were mechanical experts, reporters, a number of foreign representatives, and more importantly, what appeared to be a few members of the U.S. government. It was the exciting culmination of years of work, but even so Bangerter found himself reflecting on his recently departed friend, Dr. William Marsh, the president of Standard Meter Company, who had died a few weeks before in early 1908. Marsh had encouraged Friedrich when his efforts seemed to stall and financially backed him when they bore fruit.

Bangerter’s thoughts returned to the moment with a burst of laughter coming from a cluster of spectators. He checked his creation one last time and then exited the small wooden room appearing before the crowd of 20 or so. The conversations faded away as Bangerter stood before them. The Swiss inventor wanted to make a few remarks before starting the demonstration. First, no one would be allowed to inspect the weapon, and as such, it had been placed inside a small wooden enclosure built into the corner of the loft. A firing hole had been cut so even the barrel could not be seen. Second, his invention did not require conventional explosives nor did it use compressed air as some might think after witnessing the demonstration. In fact, it was far simpler, employing a principle that almost any technically inclined person would understand; hence the need for secrecy.

For safety reasons he had constructed a wooden partition from which his guests would be protected from any ricochets or flying debris. There were a few murmurs as the inventor asked everyone to position themselves behind the barrier and then excused himself and disappeared into the wooden enclosure. A whirling noise became apparent as Bangerter reappeared a few seconds later, and with a large scoop he began depositing several dozen ball bearings into a hopper that passed through a hole in the wooden casemate.

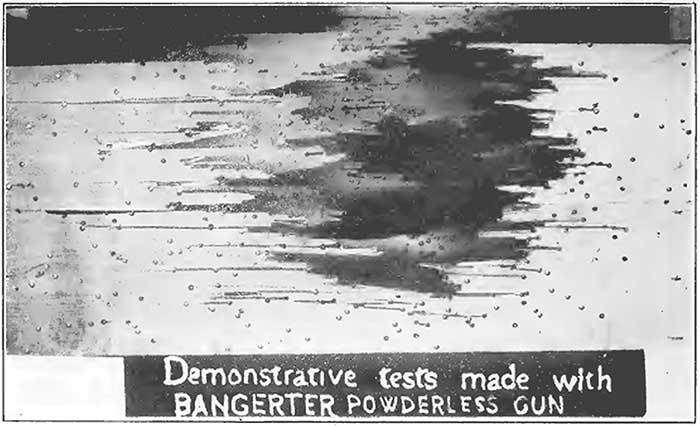

Sixty-five feet away lay a 10-foot square board of half inch pine. The center of this board immediately erupted into a shower of splinters and wooden debris as the steel balls made quick work of the obstacle. “The target seemed to melt before the eyes as the missiles struck it,” one witness recalled. Within a few seconds a hole had been punched through the wooden barrier, and the steel rounds began raining on a second target staged five-feet behind the first. Bangerter kept feeding the hopper as the ball bearings cut through the second target in a cloud of splinters and began raining upon a third barrier. “There was no explosion, no smoke, and no click of shells being forced empty from the magazine,” one observer noted. “The only sound that came from the gun was the dropping of the bullets into the funnel.”

The Swiss engineer terminated the demonstration when it was clear that the third target was on the verge of being penetrated. There was silence broken only by the occasional whisper as the whirling noise faded away. Bangerter returned to his former position before the crowd. He cut the first question off with a raised hand, knowing what was going to be asked. The whirling noise was a 7 H.P. motor which, through a flywheel, supplied the propelling force which discharged the bullets he explained. “How large were the ball bearings,” someone quickly followed? “3/8 inch,” Bangerter responded, but other sizes could easily be employed. “What was the rate of fire?” a tall gentleman asked. “Approximately 100 rounds per second,” the engineer proudly answered. There was an audible gasp from the group, while others responded by quickly jotting down notes or with a quick comment to their neighbor. It was not lost on anyone present that 6,000 rounds per minute was an unheard-of number. Nor was it lost on them that logistically, not only would ball bearings be vastly cheaper to produce than smokeless ammunition, but that given the size and nature of the projectile enough could be carried to sustain such a high rate of fire. The inventor answered a few more questions and then made a general statement to his audience.

“I have no intent of taking out patents on the gun or placing it on the market,” he started. “I realize that it would be too deadly a weapon to place within the reach of everyone. After the gun for the sixth tenth-inch (round) is completed I shall open negotiations for its sale. Of course, the United States shall have the first chance. I have already received an offer from an English syndicate. They want me to construct a gun that will come up to the British government requirements that the bullets penetrate a pine board one inch in thickness at a distance of 300 yards.”

Bangerter nodded to himself at the statement. “The gun which I shall build next will do all this and be capable of discharging 500 shots a second or 30,000 a minute. To drive this gun, a 120 H.P. motor will be necessary, but by the time the new gun is completed I will have ready a specially constructed auto truck on which the weapon will be mounted.” The engineer shrugged. “Unless the power broke down it would be impossible for the enemy to capture one of these guns, which are so simple that they can be mounted on a swivel and swung to any point of the compass. Two men, one operating the engine supplying the power and the other directing the gun, could stand off 100,000 men.”

Harnessing Centrifugal Force

Bangerter’s noiseless and smokeless machine gun impressed many in the room, but a better name for the Swiss engineer’s invention was the centrifugal machine gun. Bangerter had harnessed the circular motion generated by a motor to create what was essentially a mechanical sling shot, or as one observer commented, he had taken the sling and reduced it “to cylinder form which operated like a hydraulic turbine with a motor attached.” The ball bearing rounds were fed via a hopper into an opening in a spinning compartmented platen, which then accelerated the round until it reached the barrel or firing port. At this point the ball bearing departed the platen. As with much of the Swiss engineer’s design, it is not clear if Bangerter utilized a short barrel, a deflector plate or relied upon timing to guide the projectile forward in a linear manner as generated by conventional firearms. In fact, one sketch of the test setup made by a witness showed not one, but four barrels.

It was a simple and elegant solution that generated great interest for a number of reasons. The weapon utilized very few parts, and theoretically, the rate of fire and the exit velocity of the ball bearing projectile were a direct and easily understood function of the R.P.M. of the platen and the power needed to generate these circular speeds. More importantly, the centrifugal gun presented not only the opportunity for incredible rates of fire but logistically bypassed the standard munitions industry implying huge cost savings for the military. One writer of the time was quick to point out that the gun could be fired for an hour at the mere cost of $200 as compared to a cost of 10 to 20 times that for a conventional machine gun. “Goodbye gunpowder!” was the chant, and for a moment it appeared that the Maxim, Browning and Hotchkiss offerings of the day had found a serious competitor.

Failed Negotiations

What started with great aspirations, however, was soon mired in problems. Bangerter was looking to sell the invention to a government for 5 million dollars, or at the very least secure the investment capital needed to allow him to build the full-scale version of the weapon. The first of these options the inventor effectively nullified by refusing to let experts from the U.S. Army Ordnance Department examine the weapon. French military representatives also expressed interest, but they too quickly walked away after Bangerter refused them access to his centrifugal gun. As for securing capital, the Swiss engineer thought he had found this in a Wall Street broker, but the partnership quickly dissolved after Bangerter concluded that it had been an attempt to steal his design. Bangerter demonstrated the machine several more times, but given the success of his other inventions, the engineer’s interests waned, and he abandoned the project when neither a buyer nor an investor could be found.

To make matters worse, whether by independent work, through Bangerter’s Wall Street misdealings or by his own words describing the device, a number of centrifugal designs began to appear. These designs, however, fared no better than Bangerter’s. The demonstrations and 100 or so patents filed on the method were sufficient to attract some attention, but no serious offers were forthcoming.

Moore and Singer

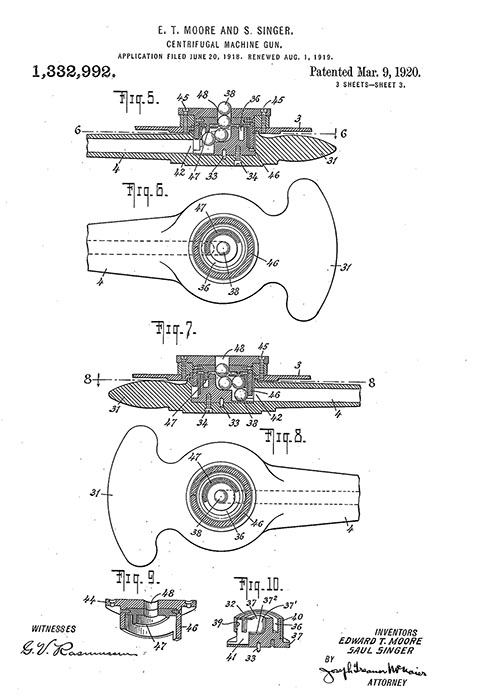

The matter seemed settled until New York Lawyer and inventor E.T. Moore and his partner Saul Singer developed a gun based on the same principles. The device consisted of a primary shaft driven by a powerful electric motor. Attached to the shaft at a right angle was a hollow 8-inch tube that acted as the ball carrier and barrel. A metal casing, or housing, covered the spinning gun barrel. An exit opening on the front of the housing was the only thing that resembled a muzzle. Moore claimed that the key to the device was in the timing. The mechanism had been adjusted so that a ball was dropped at such an interval that it emerged from the spinning barrel just as the barrel’s muzzle aligned with the housing opening. Moore, like his predecessor expounded the merits of the design, claiming that his design could fire 2,000 rounds per minute and could kill a man at a range of a mile and a half.

Moore and Singer filed for a U.S. patent in 1918 and shortly before the end of the war offered the invention to the U.S. Army. While other designs had failed to secure the interest of the Army Ordnance Department this new design was the exception, no doubt aided in part by Moore’s connections as a New York lawyer and his former position as Judge Advocate and Inspector for the New Jersey National Guard during the First World War.

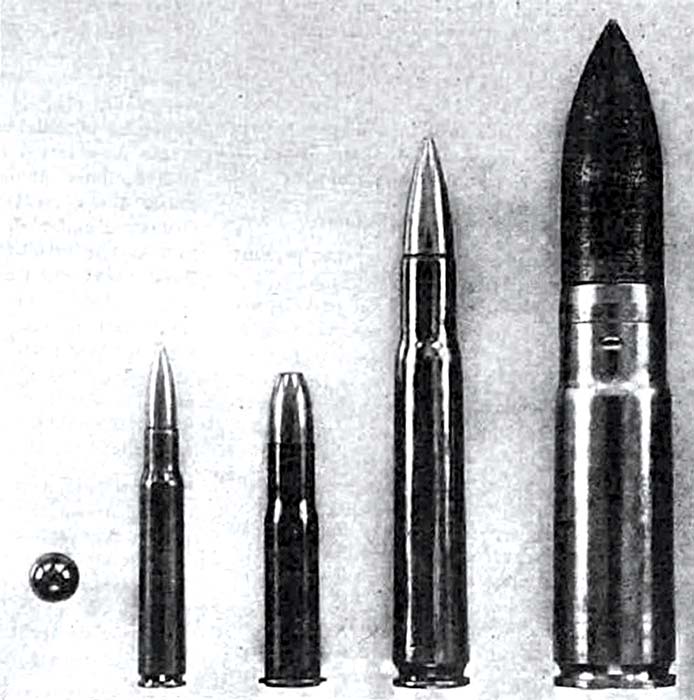

By early 1921 the Army was prepared to conduct an official test of the weapon. Having possessed the firearm for some months the Army Ordnance engineers had discovered a number of characteristics and issues with the weapon. The first problem was that although the exit velocity of the round was a direct function of the platen rotation speed, it was also dependent on the radius of the platen. This of course limited the practical size of the spinning firing wheel not only for handling reasons but for power reasons as well given the motor technology of the day. Second, although the large caliber ball bearing round was cheap, it was light (about one-sixth the weight of a contemporary .50 caliber Browning round) and aerodynamically inferior, which when combined with mechanical coupling inefficiencies and a smoothbore approach resulted in an exit velocity (F.P.M.) approximately one-tenth the circular speed (R.P.M.) of the platen. What was more disturbing was the power required to operate the gun at reasonable exit velocities and rates of fire. To achieve a speed of 16,000 R.P.M. required a 100 H.P. motor, a practical limit given the size of such motors at the time. As a result, this now confined the gun to a vehicle, which would provide a firing platform and the source of power.

Moore arrived at the Aberdeen Proving Grounds in mid-May, and tests were conducted in the following days. Firing from the back of a truck the inventor did an admirable job. The rate of fire was approximately 1,800 rounds per minute, or two to three times that of the newly made Browning M2 design. Tests showed that the ball bearing round was capable of inflicting a disabling wound at 250 yards, but the short range of the weapon was reflected in a quick fall off beyond this point. Accuracy was poor, with the main portion of a group of 2,000 rounds fired at a target 50 yards away being found to be within a 10×7-foot rectangle. There was also a significant number of outliers, which as one contemporary writer and Ordnance officer, Julian S. Hatcher, proposed was likely from the ball striking the side of the barrel in the smoothbore design.

Centrifugal Force Unmatched

Nothing in the demonstration, however, convinced the Army to continue the project. The weight and power issues, coupled with the limited mobility of the gun and its underpowered projectiles was enough for them to part ways with the idea. As one Ordnance observer noted, “It is considered as an interesting illustration of what may be done with centrifugal force but limited by the nature of the mechanism required to the status of a laboratory demonstration.”

For Bangerter it was perhaps the end of a dream, and although his invention and those that followed did not succeed, the bad news did not bother the Swiss engineer as his attention was currently focused on another invention: a conventional ammunition, 15-barreled, chain-driven, blow-forward, rotary machine-gun; a concept that is likely the most complicated machine gun design ever proposed. Given the simplicity of the centrifugal gun and the absurd complexity of his later externally driven multi-barrel rotary approach, it is safe to say that Mr. Bangerter’s work occupies the end points of the spectrum in the search for the practical machine gun.

SOURCES

“The Bangerter Noiseless, Smokeless Gun,” Arms and the Man, Jul 16, 1908.

“The Centrifugal Gun,” Army Ordnance Journal, May-Jun, 1921.

Hatcher, Julian S. “The Machine Gun of the Future,” Army Ordnance Journal, Jul-Aug, 1920.

–Hatcher’s Notebook. National Rifle Association, Virginia: 1996.

“It Really Does Shoot,” N.Y. Times, Aug 13, 1910.

“Powderless Gun a Marvel,” N.Y. Times, Jul 16, 1908.

“The Centrifugal Gun,” The Independent, Sep 4, 1920.

King (ed.). Bangerter’s Inventions: His Marvelous Time Clock. Private Printing, N.Y.: 1911.

Princeton Alumni Weekly, Vol. 21, No. 5, Nov 3, 1920.

Daily Press, Newport News, VA, Jul 19, 1908.

“De-vitalizing Warfare,” The Bellman, Apr 11, 1908.

“Fires 2,000,000 Bullets Hourly,” Washington Post, Mar 8, 1908.

“A Two Million Bullet Gun,” The United States Army and Navy Journal and Gazette, Mar 21, 1908.

E.T. Moore and Saul Singer, “Centrifugal Machine Gun,” U.S. Patent no. 1,322,992, Mar 9, 1920.

F. Bangerter, “Automatic Rapid Fire Machine Gun,” U.S. Patent no. 1,424,751, Aug 8, 1922.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V23N3 (March 2019) |