Long before “Gatling Gun” Parker’s guns made him famous by demolishing the Spanish on top of San Juan Hill, there was Lieutenant Arthur L. “Gat” Howard of the Connecticut National Guard. Born 1846 in New Hampshire and raised in Chicopee, Massachusetts, he helped make the Gatling gun famous, founded Canada’s national ammunition industry and largely determined Canada’s adoption of the machine gun.

Gat grew up in the cradle of American guns … Chicopee adjoined Springfield, home of the fabled Springfield Armory, gun makers Massachusetts Arms, Stevens and Savage and several other manufacturers and foundries.

Throughout the Civil War, firearms for the Union armies poured in from factories near Gat’s home, and the Confederacy already carried Maynard carbines made there. But Arthur L. Howard rankled under Miss Valentine inside the Chicopee Grammar School and missed the adventure. There was an A.L. Howard wounded in the 25th Connecticut. He was Alonzo, no relation to Arthur.

When the war ended in 1865 Howard was a schooled and trained machinist and still determined to be a soldier. In April 1867, he joined the First Cavalry and rode for five of the Cavalry’s most active years as the First opened the west and fought in several Indian wars.

The conflicts spilled across the border to Canada, where Gat would later make his mark. The fighting was not as bloody as in the United States. Two “rebellions,” in what would soon be Manitoba were led by the enigmatic Metis leader, Louis Riel and his friend Gabriel Dumont.

The Metis were descendants of French-Canadian fur trappers and their First Nation wives. Angry at Canada’s neglect and political abuse, the Metis declared their own Provisional Government in late 1869. The conflict remained a war of words until Christmas 1869 when the rebels executed a particularly provocative white hostage. Riel was blamed, and he fled to Montana.

Nonetheless, Canada negotiated with the provisional government and created the province of Manitoba in 1870 to settle the Metis claims. But settlers and con artists kept coming as Canada eagerly moved the Metis and First Nations out of the railway’s path. Promises were made and, once the tracks passed through, forgotten.

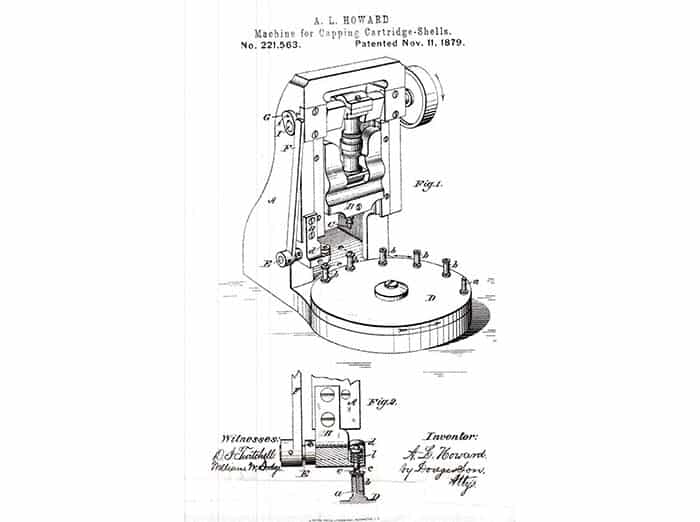

South of the border, Howard dusted out as a sergeant and returned east. He joined Winchester and shared patents for refrigeration, cartridge manufacture and carriage equipment.

He left Winchester and formed his own firm to manufacture shotgun shells. These were sold under his name and also N.Y. Club, Fowler, H.A. Co., Standard brands and Keystone Ammunition. His home factory burned down around 1881. Undaunted, Howard replaced it and, with U.S. Cartridge Co., produced the highly regarded “Black Climax” competition trap shell.

Howard still had time to join the Connecticut Army National Guard. The Gatling gun for the 2nd machine gun platoon arrived in late August 1884, and Lieutenant A.L. Howard was named to command its eight-man crew. Already an admired leader and veteran, he soon established himself as an expert with Gatling’s gun.

The gun was no longer novel. Dr. Richard Jordan Gatling had prototyped it in 1861 and first sold it in 1862. Union General Benjamin F. Butler brought it to battle, buying 12 guns for $1000 each, with his own money.

Gatling’s gun was a circle of barrels and actions clustered in a bundle. A hand crank rotated them around a central axis. Loading, firing and extraction took place at various stages in the rotation.

The first six-barrel Gatling fired 150 rounds a minute. As each barrel only fired 25 times a minute, the leisurely rate was gentle on ammunition and avoided overheating the barrels. Later guns used 10 barrels allowing higher fire rates.

A simple gravity-fed ammunition hopper was followed by a 40-round box with a single stack of cartridges. This was propped in the hopper so the rounds could fall by gravity.

In the 1871 Gatling, the rounds were held in the box by a spring stopper that moved aside when the box was inserted. The box hung out at 45-degrees on the left side of the gun so the line of sight was not blocked. After 1874, the sights were moved slightly to the right, and the magazine was mounted upright. This model was sent to Canada.

Later models introduced the highly efficient Bruce loading system and the Broadwell magazine. Finally, the Accles drum is the familiar iconic Gatling magazine. One hundred and four rounds ride in a circular drum. The empty center gives the donut look.

Northwest Rebellion of 1885

By 1874 many disillusioned Metis had left Manitoba for Saskatchewan. But, in June 1884, the situation resembled the bad old days in Manitoba and drove Riel’s old friend Gabriel Dumont, representing a new rebel leadership, to Montana. Riel was persuaded to return to Canada in July with his wife and two children.

His supporters expected Riel to lead their negotiations. He shocked them by raising a small army.

In March 1885, desperation grew. A punishing winter drained cellars, larders and storerooms. Northwest Mounted Police Inspector Leif Crozier sent men from Fort Carlton to commandeer the supplies at the Duck Lake Hudson Bay Company store.

The Metis had already moved first, looting the stores and blocking the road. The surprised NWMP turned back to Fort Carlton.

Crozier quickly assembled and led 53 police and 47 armed civilians to confront the Metis. When Riel heard that a contingent of Northwest Mounted Police was coming, he called reinforcements, and near Duck Lake they made contact.

The police used their dog sleds as shields. A cautious parlay began. An unexpected shot was fired, likely in misunderstanding, and Gabriel Dumont’s brother fell dead. Crozier and his men charged the Metis several times, losing bloodily each time.

A single cannonball brought it to an end. The loaders got out of sync, and a ball was jammed on an empty chamber. With the 7-pounder useless, Crozier retreated, leaving 12 civilian volunteers and five rebels dead. Five more of Crozier’s men died later of wounds, and a captured volunteer was saved from being scalped by Riel’s personal intervention.

Crozier returned to Fort Carlton and decided to abandon the fort. Intentionally or accidentally, it burned to the ground as Crozier retreated to Prince Albert.

Telegraph wires carried the news to Canada’s capital Ottawa, and the fury of a disrespected government rose. The militia was called out.

The Metis victory at Duck Lake inspired the Cree to move on Battleford, 116 miles to the west, late in March. The Cree had earlier moved agreeably to their reserve but found there were few buffalo, little game and the supplies promised were not forthcoming. The local “Indian Agent,” Thomas Quinn, seemed determined to starve the tribe.

On their way to join the Cree, angry Assiniboines killed several whites. Immediately the people of Battleford swarmed the police fort for safety as the tribes erected a huge camp. The police suddenly had 500 civilian guests when the hungry Cree approached for food. The Indian agent, Mr. Rae, refused to leave the fort or meet them. Would-be rescuers to the south are cut off by high spring water.

Frog Lake Massacre

On the night of April 1, 139 miles northwest of Battleford, at Frog Lake, Cree warriors raided the government stores, the HBC post and the general store owned by George Dill. The next morning, a Sunday, the Cree ordered the white civilians to leave church and go to the nearby Cree camp. The infuriated Quinn refused. The equally infuriated war chief Wandering Spirit shot Quinn in the head. Chief Big Bear intervened too late, and two priests, their lay assistant and several male settlers, including George Dill, were killed. The Frog Lake Massacre turned a problem into a war.

On the same day, the New York Times reported Chief Poundmaker’s “Indians entered Battleford, plundering deserted houses” as their owners watched from the fort. Two cannon shells chased the looters out.

Back east, British Major-General Frederick Middleton, commander of the Canadian Militia organized preparations. The Minister of Militia ordered 10,000 Martini-Henry rifles from England to arm the gathering forces. The rifles arrived 10 days later. Noting Custer went to Little Big Horn leaving his Gatling guns behind, Middleton suggested his expedition take two Gatling guns.

Canada asked Colt for the Gating guns, with traditional parsimony, without charge. Gatling himself, now the next door neighbor of Colt’s widow, encouraged the loan.

As there were no qualified gunners in Canada, Gatling sought out and asked Lieutenant Howard to accompany the expedition as a “friend of the guns.” Howard eagerly agreed. In Hartford, Gatling and Howard saw the Gatling guns and 5000 rounds of ammunition loaded on a train for Winnipeg. Howard boarded with them.

In Canada, Riel and the Provisional Government of Metis moved into the town of Batoche and declared it their capital. The rebels surrounded the town with rifle pits.

Canadian troops were converging from the east and west. Middleton had about 5500 troops available, including 3000 regulars, 2000 volunteers and 500 NWMP. About 900 would see use.

Howard had little time to train the Gatling gunners before the army arrived at Qu’Appelle. General Middleton and 800 of his men, including Captain Howard and one of the Gatling guns, got off the train to head north for Batoche. Middleton sent Lt. Colonel William Otter with 750 men and the second Gatling gun further west by train to then march north and relieve Battleford.

Gabriel Dumont ambushed Middleton’s column and approached Fish Creek on April 24. Despite Middleton’s cautious advance and reconnaissance, Gabriel Dumont’s field craft caught the soldiers in a ferocious ambush. There was no chance to deploy the Gatling. Both sides took losses. Middleton camped and tended the wounded for two weeks.

The same day that Middleton was ambushed, Otter and men reached Battleford. Since no one ventured from the fort, they didn’t know that the Metis and the tribes had left. The locals demanded revenge, and Otter’s officers and men cursed missing their big chance. Disregarding his orders to stay in Battleford, Otter takes 325 soldiers and policemen, two cannons and his Gatling gun in pursuit of the rebels.

A week later, Otter finds Chief Poundmaker’s teepee village sited between flanking ravines. The rear is protected by a hill and the front by a marsh and creek. Prepared rifle pits faced Otter’s advance.

Otter’s artillery officer, Major Charles John Short, sited his Gatling alongside the 7-pound cannons. Otter opened fire with all guns. Families burst from the teepees and scattered to the ravines.

A few dozen warriors charged Otter but quickly fell back. Otter sent his men forward. The rebel warriors numbered between 50 to 250 men and boys guided by Poundmaker’s War Chief from his vantage point on a flanking hill. He watched Otter’s moves and calmly directed counter-attacks from the ravines, thwarting Otter repeatedly.

War Chief Fine Day led a group through a ravine to attack the guns. Major Short and several men killed two warriors and wounded a third. Short lost one man shot dead in the head, and three more were seriously wounded. Another soldier died from a bullet in the mouth while covering the Major’s retreat.

After six hours, Otter ordered his demoralized men to withdraw. Warriors mounted their horses to give chase through the marsh. The Gatling came to the rescue and prevented a remake of the Little Big Horn. Eight soldiers and six Cree were dead. Otter arrived back in Battleford and declared the action a successful “reconnaissance in force.”

To the east, Middleton finally neared Batoche. The fortifications consisted of rifle pits with log shields. The defenders were not well-armed. Earlier, many had bought Winchester 1866s, 1873s and 1876s or traded for older Sharps, Springfields and Henry rifles. But when the tribal wars ceased and the buffalo herds vanished, so did the need for those guns.

By 1885, most Metis had sold the guns to buy food. They replaced them with cheap trade shotguns—mainly percussion muzzle-loaders. The common Hollis & Sons and Parker-Fields were mostly 24-gauge smooth-bores with 2- to 3-foot barrels. There were a few flintlocks, and the boys who accompanied their fathers carried bows and arrows which did no recorded harm.

On May 9, 1885, Middleton’s combined operation to encircle Batoche would open with a ground assault. Howard was ready to show what the Gatling could do. This would distract the defenders from the steamboat Northcote powering upriver behind them to land a force of 50 men.

But, the Northcote, cloaked in improvised armor, arrived early and sailed straight into a ferry cable the defenders had lowered across the river. Her stacks crashed down in clouds of smoke and steam, and the crippled vessel drifted downstream to historic oblivion.

Middleton ordered his artillery and Howard’s Gatling gun to open fire on two houses near the church.

As one house began to burn, Howard swung his Gatling to shoot up the church. A white flag quickly waved. Howard stopped, and several priests, nuns, women and children run across the lines to safety.

Suddenly, disaster threatened. Just yards from the cannon, Gabriel Dumont led a rebel rush from the bush. Middleton anxiously ordered the guns to pull back. For long minutes the battle hung in the balance. Then, resplendent in his U.S uniform, Howard pushed his Gatling forward and turned it to the threat. Cranking rounds into the rebels, he killed and wounded several, breaking the charge. Seeing that Howard averted calamity, Middleton sent the cannons up again and regained the initiative. The Toronto newspapers christened Howard as “Gat.” It stuck.

Middleton ordered a few tentative probes, and at the end of the day ordered his men to a safe camp for the night.

He returned the next morning, May 10, and again directed his artillery and Howard’s Gatling to batter the town. His half-hearted advances were blunted.

On May 11, Middleton realized the Metis were running out of ammunition, and their line had thinned. Barely one in four Metis remained in the rifle pits, all reduced to reloading with rocks, cutlery and spent bullets found in the dirt. The next day, Middleton ordered a two-pronged assault to take Batoche, but the signal for the second prong to attack went unheard in the wind.

Bitterly unhappy with his amateur soldiers, Middleton again pulled back his men and retired fuming for lunch. His frustrated men charged the rifle pits and chased out the few remaining rebels. Middleton rushed to the scene. Each side lost about 25 men. Gat Howard personally seized the rebel flag from atop the church.

The rebellion was broken. On May 15, Louis Riel surrendered. After much indecision, he was hung on November 16.

Arthur L. Gat Howard, now a Canadian hero, was hastily listed as a Lieutenant in the Canadian Mounted Rifles and awarded the Northwest Canada 1885 Medal.

Efforts by Canadian government researchers have been unsuccessful in determining the fate of the two Gatling guns, despite various claims.

Howard’s Next Steps

Howard did not return immediately to Connecticut. He convinced the Canadian government to create its own ammunition industry and hire him to do it.

It was a huge and successful undertaking. Gat designed, founded and built the Dominion Cartridge Company (DCC) in 1886 in Brownsville, Quebec. He became a very wealthy man. After several amalgamations, DCC became Canadian Industries Limited (CIL). CIL was a cornerstone of the Canadian arms industry and later provided most of the ammunition and explosives for the Canadian Army in both world wars.

But Gat’s success was marred when his wife, Sarah, refused to bring their five children to the wilds of Quebec. Howard returned home unexpectedly and found her in the company of another man. They reconciled, but he returned alone to work in Canada and await her arrival.

But Sarah resumed her affair, and again Howard returned home unannounced. Fleeing from being “summarily punished,” Sarah stumbled in her slippers and night coat through a snow-covered partially assembled circus. Howard’s lawyer served the divorce to Mrs. Howard at her boyfriend’s. Howard took the children to Brownsburg.

Gat remarried but his young wife, Margaret Green, died in childbirth a few days before Christmas 1897.

Two weeks later, Gat’s son Horace drove him to the railway station to leave for the Boer War in South Africa. Howard had earlier offered to provide Canada with a machine gun section at his own expense, but instead was made the machine gun officer in the Canadian Dragoons. For the next year, Howard commanded a Maxim and one of the new 1895 Colt machine guns.

When Howard’s unit went home in December 1900, Howard stayed on to create and command the 50-man Canadian Scouts. He equipped the Scouts with six of the new air-cooled Colt 1895 machine guns. The Scouts’ experiences with the guns led to Canada’s adoption of the Colt and its eventual use in WWI.

February 17, 1901, was the day after his 57th birthday. Typically, Howard led from the front, and help was a mile behind when several dozen Boers surrounded Howard and his orderly. They gunned them down. Howard was buried in South Africa.

The commander, Lord Kitchener, noted Major Howard had been repeatedly brought to his attention for acts of gallantry. Gat was awarded the South Africa Medal with service bars for Johannesburg, Diamond Hill, Belfast, Cape Colony and Orange Free State and posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

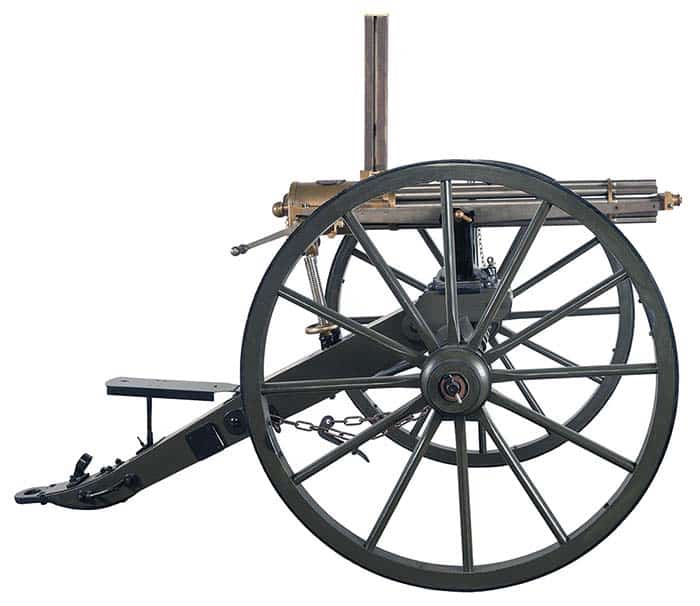

GATLING 1874 SPECS AND INFO

Price–A newly made Gatling from Colt runs in the $50,000 range while a nice original 1874 would be a bargain at $100,000. The first models sold during the Civil War went for $1000 each at the time. Replicas in various sizes, calibers and quality listed for everything in between.

Model–The gun used by Gat Howard at Batoche appears to have been the “Long” 1874 Model. There was also a shorter version known as the “Camel” gun.

Caliber–The 1874, as used by Gat, fired the brass cartridge 45-70-500 cartridge. Foreign buyers could order their guns in any caliber desired.

Crew–Only one man was needed to aim and fire the gun, but the crew would typically also include a commander and men to carry, change and load magazines, handle the carriage and manage the horses.

Range–The 45-70-500 (.45 caliber-70 grains black powder-500 grain bullet) cartridge could hit a man-sized target out to 300 yards and deliver a lethal blow at over 3000 yards. An oscillator was used to guide fire horizontally when fired from the heavy carriage.

Rate of fire–400 rpm. Earlier models utilized pre-loaded chambers and paper cartridges; these kept the fire rate under 200rpm. As design and feed systems evolved, the rate increased until experimental electric models around 1900 reached over 1000rpm. Ultimately, modern “Gating”-type guns typically reach well over 6000prm.

Feed type–Gravity-fed, top-mounted, single-stack magazine. The 1874 marked the departure of the slanted magazine in favor of the vertical stack and offset sights. This vertical feed design also lent itself to the Broadwell drum.

Number of barrels–The Long model 1874 had ten 32-inch, “musket-length,” rifled steel barrels clustered in a circle. These were round at the breech and morphed into octagonal at the muzzles. Each had its own breech mechanism creating a self-contained firearm. The Camel model had 18-inch barrels.

Length–49 inches for the Long model 1874.

Weight–The Long 1874 guns weighed about 200 pounds unloaded. The carriage as used by Gat weighed another 700-plus pounds. The Camel model had 18-inch barrels and parts reduced in size and made from brass to save weight.

Mode of fire–Mechanical. The gun is fired by rotating the crank handle. The handle was located on the right (from the gunner’s perspective) and rotated clockwise when viewed from the right side. The barrels (viewed from the rear) rotated clockwise. Each barrel fired on reaching six-clock.

Evolution–The 1874 mechanism is lighter than previous models and incorporates a raceway cam that engages the individual bolts to facilitate loading, firing, extraction and ejection. Earlier models utilized built-in cams and ramps to accomplish the same things. The improved raceway and lighter bolts resulted in a lighter mechanism.

Manufacturer–The guns sent to Canada left directly from Colt where they were made. Reputedly, Gatling and Gat Howard selected the individual guns themselves.

••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

Gat Howard is remembered in the Canadian war museum and history books. His descendent Gina Sammis has generously assembled a wealth of material about her famed ancestor. I am also indebted to Jim and Lynn Samalea, Scott Whiting, Doug Light, Carol Mintoff, Lisa Weder, Adam Bucci, Shakeena Hearn, Movie Armaments Group, G.N. Dentay and the late R. Blake Stevens.

The author has written numerous articles for Soldier of Fortune, Small Arms Review and Small Arms Defense Journal. His earlier books are available on Kindle.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V23N4 (April 2019) |