By Dean Roxby

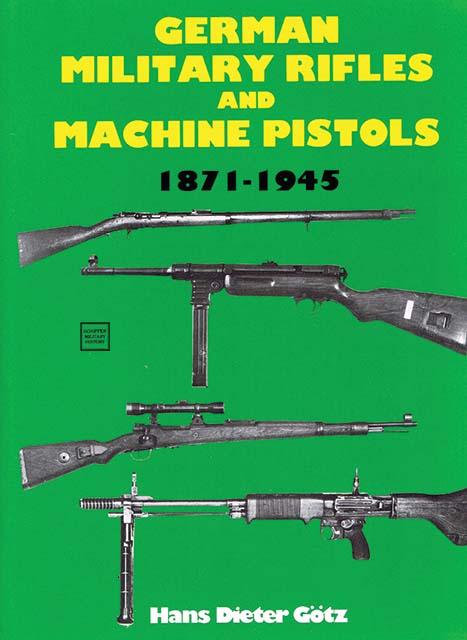

German Military Rifles and Machine Pistols 1871–1945

- Author: Hans-Dieter Götz

- Publisher: Schiffer Publishing Ltd.

- ISBN: 978-0-88740-264-7

- Copyright: 1990

- Hardcover, with dustcover: 8.5”x11.5”, 248 pages, B&W only photos and illustrations

- Available from publisher website or Amazon

Although this book is now 30 years old, it is still a great resource. It covers a specific time frame (beginning just after the Franco-Prussian War and the creation of the German Empire, and ending at the end of WWII), so it does not become stale with the introduction of current weapons.

Originally published in German under the title Die deutschen Militargewehre und Maschinenpistolen 1871–1945, author Hans-Dieter Götz describes all the rifles and machine pistols (submachine guns) in service or developed and tested during this time.

The book begins with the Werder M/69 breech loading rifle, a design that uses a dropping block action similar to the Peabody and Martini actions. The M/69 fires a brass cased 11x50mmR cartridge, rather than paper cartridges of earlier service rifles.

Following a detailed look at numerous variants of the Werder M/69, it then tackles the long evolution of the Mauser rifles, from the M/71 infantry rifle to the K98k (Karabiner 98 “kurz,” meaning “short”) that played such a prominent role in WWII. This long list of variants includes the M/71, M 71/84, Infanteriegewehr (infantry rifle) 88 (the “M” prefix was dropped at this time), 88/97 rifle and the 98 rifle and carbine.

During WWII, Germany explored the idea of building a self-loading battle rifle, no doubt inspired by the U.S. M1 Garand and the Soviet SVT-40 rifles. Actually, in the mid-1930s, Germany had begun to consider a semi-auto rifle before the War, but it didn’t go very far. Several designs from different factories were tested. The three designs that did see combat testing were the Mauser G41 (M) and the Walther G41 (W), followed by the G43. The “M” and “W” suffixes are the initials of Mauser and Walther, as both share the same year. The G43 was an improved version of the G41 (W) and was also designed by Walther. Götz covers these three rifles in detail.

At about the same time as the Army was pursuing a semi-auto rifle, the Luftwaffe was also in search of a selective-fire rifle for their paratroopers. This eventually became the Fallschirmjägergewehr (paratrooper rifle) FG 42. Seven pages are given to this intriguing rifle.

At the same time as the German Army was developing a self-loading rifle that fired the full power 8x57mm cartridge, work was also taking place on a new class of firearms that fired an intermediate-sized round. This eventually became the Sturmgewehr 44, or StG 44.

The StG 44 is covered, of course, and so too is the long path leading to its adoption. The concept of a select-fire weapon firing a medium powered cartridge had been suggested and rejected several times before finally been accepted.

A chapter is given to the development of the intermediate round (more powerful than a pistol round, but less than the full power 8x57mm cartridge). This became the 8x33mm cartridge. Also part of the StG 44’s development path was the adoption of sheet metal stamping for more efficient manufacturing. This is briefly touched on as well.

Lesser known prototypes such as the Vollmer M35 machine carbine, the Haenel MKb 42(H) and the MKb 42(W) by Walther are covered. These are of interest because features from both the Haenel and the Walther design found their way into the StG 44.

While the majority of the book discusses rifles, there is a smaller section that deals with submachine guns, Machinenpistolen in German. This section begins with the Bergmann MP18 designed by Hugo Schmeisser at the end of WWI and his later MP28/II. It then looks at designs such as the ERMA Machine Pistol (EMP), the Austrian Steyr-Solothurn MP34 and the Bergmann MP35, as well as others. Naturally, the iconic MP38 and MP40 subguns are covered; although I had hoped for a more detailed examination. Five pages do not do this design justice. The subgun section ends with a look at the MP 3008, also known as the Gerät Neumünster as well as the elusive Gerät Potsdam. The Gerät Neumünster was a close copy of the British STEN gun, while the Potsdam was an exact copy, including English receiver markings. While there is plenty of speculation, there seems to be no actual verified explanation for this.

Along with the technical details of the various arms covered, the author Götz explains the political history, business dealings and other issues of the day that shaped the choices made. As Götz says in the Introduction, “This book, therefore, will not tell of great technical achievements alone, but also of missed chances, mistakes and misdeeds.”

In addition to the various firearms examined, Götz also profiles several of the inventors behind the designs. Profiled are Wilhelm and Paul Mauser, Carl Walther and his son Fritz and Hugo Schmeisser, along with some lesser known inventors.

As this book is a translation of the original German language book, there are a few technical terms that didn’t translate properly. A receiver is called a case or casing, magazine well is called insertion socket, and my personal favourite, muzzle blast is called puff. I noted about a dozen such terms. Having said that, I do consider this a very solid reference for those interested in German small arms. A few awkward terms should not be a deal-breaker.

For those interested, note that Schiffer Publishing has a large selection of military and aviation history books listed on their website (schifferbooks.com).

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V24N8 (Oct 2020) |