Dean Roxby

In-Depth Look at Maxim and Vickers in WWII

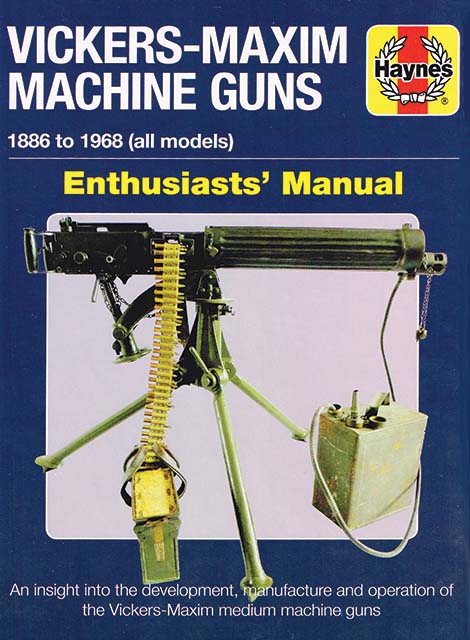

Vickers-Maxim Machine Guns Enthusiast’s Manual: 1886 to 1968 (All Models)

- Author: Martin Pegler

- Publisher: Haynes Publishing

- ISBN: 978 1 78521 563 6

- Copyright: 2019

- Hardcover: 8.5” x 11”, 172 pages

- MSRP: $36.95

This is the second of two separate, unrelated books about the legendary Vickers machine gun by author Martin Pegler, former Senior Curator of the Royal Armouries Museum Leeds, England.

Regular readers of this column may recall a review in SAR Vol. 23, No. 4 (April 2019) where I reviewed four books from the Weapon series by Osprey Publishing. One of those books also dealt with the Maxim and Vickers family of guns (The Vickers-Maxim Machine Gun, WPN 25).

As I have noted previously, the booklets that make up the Osprey Weapon series are fine books, but at only 80 pages, they are best regarded as an introduction to a given topic.

This new book by Haynes Publishing (yes, the car manual folks) covers the Maxim and Vickers guns in much greater detail. Fortunately, this reads like a book, not a repair manual. After the usual Acknowledgements and Introduction chapters, there is a historical look back at the earliest types of repeating arms. These generally were of the multiple barrel “volley” gun or of the revolving type, best described as an overgrown revolver that fires rifle or small cannon rounds. These volley and revolving guns were usually mounted on a tripod or stand of some sort. They were manually fired, and they all had a limited number of rounds.

Following these, came the hand-cranked designs by Gardner, Nordenfelt, Gatling and others. It was at this time that Hiram S. Maxim designed the weapon that changed warfare. Author Martin Pegler covers these early hand-cranked guns in detail in Chapter 1, “The Machine Gun Concept.” Chapter 2, “Trials and Tribulations,” begins with a look at Maxim himself. Maxim was a fascinating man, a true genius when it came to inventions. He had over 80 patents by age 44 for a wide range of items. Over half were for electrical equipment, as he was fascinated by electricity. After a conversation with a friend, Maxim set about to invent a gun that could load, fire and eject all by itself. There are several great old drawings that illustrate his earliest prototypes. Along with these drawings, there are several photographs from the era depicting these guns, plus two current photos of two prototypes belonging to the Royal Armouries Museum. I really like the layout of this chapter.

Pegler then covers the company merger with the Vickers Shipbuilding and Engineering company, WWI manufacture and WWII manufacture in chapters 3, 4 and 5. Again, we are treated to a great selection of photos, both from the era and current times. The photos that date from the Wars are black and white, naturally. The current photos, primarily of equipment and various accessories and parts, are in full color.

Chapter 6, “The Vickers in Service,” deals with the ground guns naturally, but it also covers guns mounted on biplane fighters. This information is seldom seen. Chapter 7, “Vickers Variants,” looks at guns mounted on vehicles and tanks. Included here is a look at the scaled-up .5-inch (similar to the .50BMG round) and the follow-up 12.7mm Class D gun. Again, the author has provided many interesting photos detailing these variants.

Chapter 8, “Maintaining and Shooting a Vickers,” promises “the sequences for stripping and cleaning a gun are examined along with detailed supporting images and technical drawings covering every part of the guns and their components.” This sounds impressive, but don’t throw out your original military manuals just yet. Yes, it does go into some detail on how to change a barrel without losing all the cooling water and swap out major assemblies like the feedblock and lock, but it will not make you an armourer. If you own a live gun that isn’t running right, this chapter may point you in the right direction, but you likely will need more detailed info. Having said this, the Vickers and Maxim design is an amazingly complex mechanism, so this comment should not be taken as a complaint.

Chapter 9, “A User’s View,” tells the history via quotes from soldiers that used the gun in combat, including one recollection by the author’s uncle. I find this memory ties the chapter together nicely and makes it relatable.

Enthusiast’s Manual is an appropriate subtitle for this book. Fans of the Vickers will appreciate the more in-depth study of one of the great guns of the Great War. It features many wonderful old period photos, interesting drawings and diagrams from the prototypes and lots of modern color photos of the gun and accessories.

At 172 pages, it fits well between the Osprey booklet and the forthcoming The Vickers Machine Gun: Pride of the Emma Gees by Dolf Goldsmith.

All You Need to Know About Black Powder Shooting

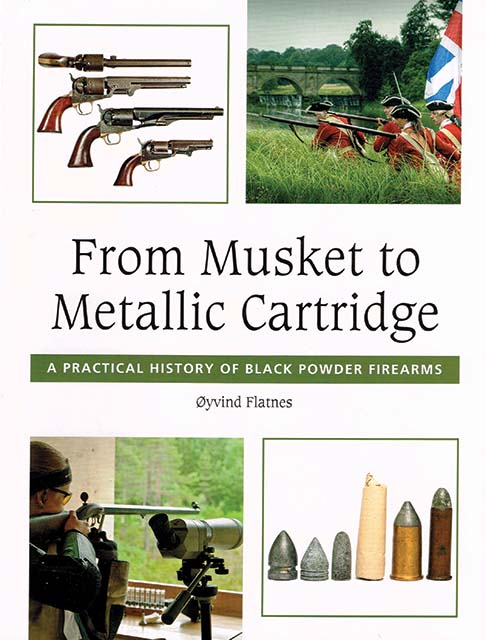

From Musket to Metallic Cartridge: A Practical History of Black Powder Firearms

- Author: Oyvind Flatnes

- Publisher: The Crowood Press

- ISBN: 978 1 84797 593 5

- Copyright: 2013

- Hardcover: 7.5” x 9.8”, 240 pages, 265 color photos and diagrams

- MSRP: Barnes & Noble $54.95

I picked up this book a couple of years ago, as part of the background research for an article on the French M1866 Chassepot “needle-gun” rifle. Upon re-reading it recently, I felt it was worthy of a full review here.

The title of this book perfectly sums it up nicely. It covers the history of black powder firearms from the earliest of muskets through to the advent of self-contained metallic cartridges. Rather than just a dry history lesson, it offers a great deal of practical information on safety, gun maintenance, loading and cleaning, etc.

The first chapter, “Age of Firearms,” is a quick overview of the technical progress made since the beginning of the firearms era, probably the early 1200s. Chapter 2, “The Gun in Warfare,” looks back at roughly 500 years of conflict and how the firearm changed battle tactics. As most of the wars involving guns were occurring in Europe, this is where the bulk of the development was occurring. Several of these wars are mentioned. Of course, the American War of Independence and the Civil War are also covered.

The book is presented in a chronological order, with improvements to the ignition systems following a logical progression from matchlock, wheel-lock, flintlock, to percussion caplock; then the transformation from external ignition to self-contained cartridges is covered.

While rifles make up the majority of the subject matter, there are chapters dedicated to pistols as well. Cap and ball revolvers are covered, certainly, but older designs like flintlock and even matchlock pistols are profiled. The author points out that so-called “duelling pistols” were seldom advertised by that term. More correctly, they were target pistols that ended up being used in a duel.

As mentioned above, this book contains a great deal of practical information for anyone wanting to fire black powder. The instructions and diagrams on how to recreate paper cartridges will be especially useful for anyone wanting to warm up an old relic.

Early black powder cartridge rifles such as the British Martini–Henry, the Springfield M1873 Trapdoor and others are covered in Chapter 11, “The Single-Shot Cartridge Rifle” and Chapter 12, “The Repeating Rifle.” A chapter on “Cartridge Revolvers” follows. Although primarily a history of the evolution of cartridge firing guns, these chapters also have some useful loading information as well.

Sections on making paper-patched bullets and even on reloading pinfire ammo are especially interesting. Chapter 15 gives a very good explanation of what is required to reload black powder cartridges. Powder, bullets, lube, wads, case annealing, powder compression and more are thoroughly explained.

Black powder shotguns are not forgotten either. Both muzzle-loading and breech-loaded cartridge-type shotguns are dealt with. As modern plastic hulls don’t work well with black powder, older paper hulls and all-brass cases are discussed.

The chapter on hunting is interesting to read from a historical perspective; although I did find myself getting angry at the colossal waste that took place during the bison hunts on the Great Plains.

The book ends with a chapter on the various groups within the larger black powder community. Reenactors of various battles (Napoleonic Wars, colonial America, the Anglo-Zulu War and the American–Indian Wars are common subjects), the North-South Skirmish Association and Cowboy Action Shooters are mentioned.

I believe this book will be a valuable resource for those wanting to shoot black powder guns from any era. I also found it to be a great study into the history and development of the firearm from the very beginning, up to the transition to smokeless powder in the late 1800s.

Well-illustrated with 265 color photos and diagrams, laid out in an orderly fashion and delivering the right blend of historical context, technical descriptions of weapons and practical advice makes this a book worth considering.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V24N6 (June/July 2020) |