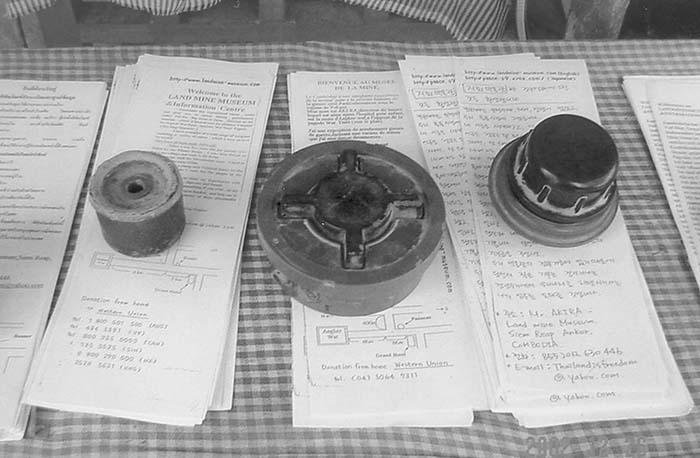

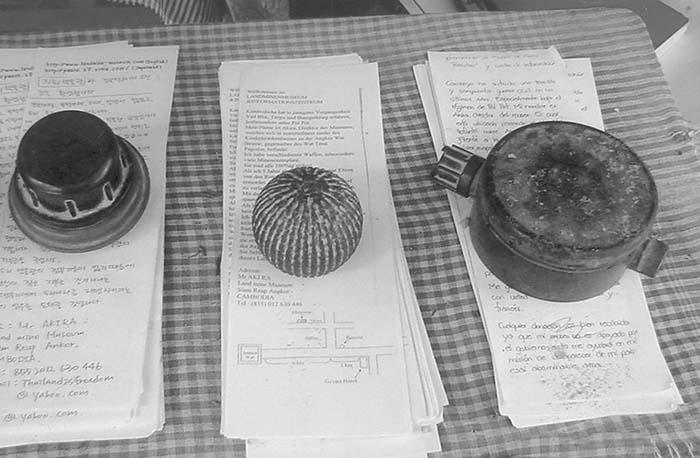

A display of landmines recovered from the Cambodian countryside.

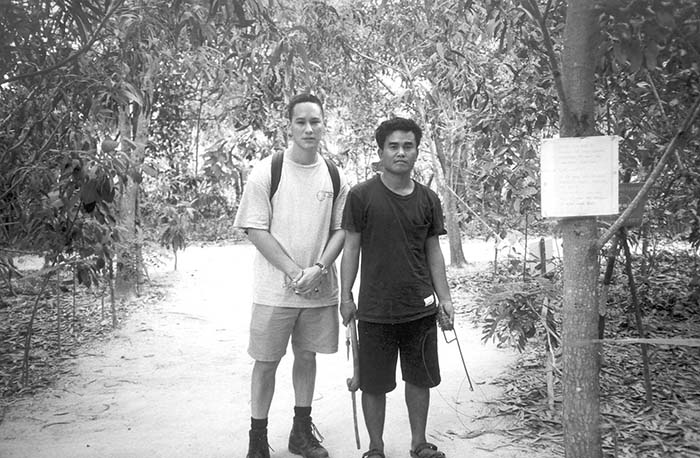

by Jason Wong

Cambodia. The mere mention of the country brings about images of triple canopy jungles and fabulous temples. For some, the country also symbolizes fear, civil war, and horrific crimes committed by the Khmer Rouge. Civil unrest and war swept through Cambodia on a nearly continuous basis from the French Indochina War following World War II, until the end of civil war in 1998. The consequences of the long periods of fighting have resulted in untold tons of unexploded ordnance, land mines, and booby traps scattered through out the country. As an agrarian society, the population relies upon being able to graze domesticated animals and farm for subsistence. Due to the large number of unexploded ordnance (whether accidental, such as unexploded RPG-7 rounds, or deliberate, such as Russian PMN-2 land mines) the population has long been held captive to unseen dangers lurking under the soil.

Recent efforts have been undertaken to discover, disarm, and remove unexploded ordnance within Cambodia. As a former guerilla fighter, Mr. Aki Ra has undertaken a personal mission to rid the country of these hidden dangers, one piece at a time. The results of his efforts can be seen at the Cambodian Landmine Museum, created to display the items he has recovered and deactivated. The Landmine Museum, located in the town of Siem Reap, is just outside the ancient temple boundaries of Angkor Wat. Upon entering, the visitor immediately recognizes that this is not a typical museum display of ordnance. Visitors are immediately overwhelmed by several huge piles of Russian PMN, PMN-2 and MN-79 anti-personnel mines, each standing over four feet tall and covering an area measuring fifteen square feet, representing thousands of individual mines. Close examination of other displays reveal obscure Vietnamese P-40 “Apple mines” made of recycled cast iron, ancient Soviet PMD-6 anti-personnel landmines made out of wooden boxes, defused American-made 60mm, and 81mm mortar shells, and Vietnamese B-40 RPG rockets. As all objects within the museum have been rendered safe, visitors are free to pick up and examine all of the ordnance on display in detail.

Mr. Ra presents an interesting story of how he came to be a landmine expert and museum curator. Starting from the mid-1970s, Cambodia was torn by several guerrilla factions battling for control over the country. As a result, he does not know exactly how old he is, but estimates that he was born in 1973. At the age of 5, both of his parents were killed by the Khmer Rouge. As an orphan, he was cared for by the Khmer Rouge, and taught to fight in the jungle. Being of small stature, one of the first tasks assigned to Ra was to create a minefield to thwart Cambodian forces in the area. At the age of 13, his village was attacked and overrun by Vietnamese-based soldiers. Given the choice of fighting for the Vietnamese or being executed, he chose to fight for the Vietnamese based guerrilla fighters and continued to fight against the Khmer Rouge until 1990, when he joined the then newly formed Cambodian Army. National elections for a new government, supervised by the United Nations, resulted in the need for interpreters in 1993, when Ra volunteered to work for the United Nations. Upon completion of election process, the United Nations trained Mr. Ra and other Cambodian nationals to discover and disarm unexploded ordnance, leading to his current role as an expert in the field of unexploded ordnance.

While touring the museum, Mr. Ra took the time to introduce the author to the Russian PMN-2 landmine. A product of the former Soviet Union, it is identified by a light green injection molded plastic body, approximately 5 inches in diameter, with a black rubber pressure plate in the shape of an “X.” Mr. Ra explained that unlike Hollywood depictions, modern landmines make no audible click upon being stepped on, nor is there a delay before exploding. To illustrate, Mr. Ra disassembled a deactivated Soviet PMN-2 landmine, and described the internal parts, pointing out the firing pin and firing mechanism. Mr. Ra then armed the landmine, placed it on the ground, and proceeded to step on it. Requiring only 5 kilograms (11 pounds) of pressure to detonate, the landmine acted immediately upon being stepped on. Because it was deactivated and did not contain an explosive charge, the only result was the firing pin flying across the dirt floor of the museum, and into a pile of Soviet MD-82B anti-personnel landmines. Mr. Ra dismissed the loss and commented that he had many more landmines by which to conduct another demonstration to future visitors. For the sheer thrill of being able to openly handle a large number and variety of anti-personnel and anti-tank ordnance, the Landmine Museum was well worth the detour from Angkor Wat and should not be missed.

GETTING THERE

Travel to Cambodia has become relatively easy in recent years. Direct flights are available to Siem Reap from the capital of Phnom Penh, or from Bangkok, Thailand. For those who are more adventurous, overland travel from Bangkok is easy and inexpensive, but long and mildly uncomfortable.

The museum itself is located off the beaten track, in a residential neighborhood of Siem Reap. No admission is charged, but as a privately run museum, donations of any kind, (whether monetary, or in the form of candy, pens, or writing materials) are welcomed and appreciated. At press time, there was some concern that the Cambodian government may attempt to shut down the museum; government officials “confiscated” a large number of ordnance and artifacts for the “official” Landmine museum being planned by the Cambodian government.

Additional information regarding the Cambodian Landmine Museum, including first hand accounts of Mr. Ra’s fight against the Khmer Rouge, and maps to the museum can be found online at http://www.landmine-museum.com/

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V7N11 (August 2004) |