By Frank Iannamico

The early M16 rifles were issued in relatively small numbers to U.S. military advisors and Special Forces personnel serving in Vietnam and the Air Force’s Air Police. Feedback from the field resulted in a few changes to the original design. The barrel twist was changed from 1:14 to 1:12 to increase accuracy, and a bolt closure device, known as the forward assist, was added; USAF models did not have a forward assist. The updated M16 was designated as the XM16E1: X = experimental, E1 = Evolution 1.

The M16A1 rifle slowly evolved from the XM16E1 initially fielded in large numbers during 1964 to the U.S. Standard A infantry weapon, officially adopted in 1967.

The adoption of the 5.56mm M16 during the war in Vietnam was to replace the M14 rifle that was proving to be too cumbersome, too heavy and its 7.62mm cartridge too powerful for the type of engagements being encountered in the jungles of Vietnam. What was needed was a handy weapon that was light in weight, controllable in full-automatic fire and one with a small 5.56mm cartridge that would allow the infantryman to carry a larger ammunition load; a weapon that could match the firepower from the enemy’s AK rifle.

The M16 rifle was a revolutionary design made of unconventional materials that included aluminum and plastic. The weapon’s appearance and lightweight and relatively small cartridge were not readily accepted by the military establishment or many of the younger soldiers who did most of the fighting. As a result, the M16 was bestowed with the condescending rumor that they were being made by the Mattel® toy company.

The XM16E1

The first contract to purchase M16 and XM16E1 rifles was awarded to Colt on November 4, 1963. The contract was for 104,000 rifles; 85,000 XM16E1 rifles with the forward assist feature and 19,000 M16 rifles without the forward assist for the Air Force. The cost of the XM16E1 was $121.84 per rifle, the M16 cost was $112.00 per rifle. The initial contract was considered to be a “one-time” purchase until the Special Purpose Individual Weapon, more commonly known by the acronym SPIW, was perfected and put into production—adoption of the SPIW was estimated to be in 1965.

The SPIW program began in 1959 after a number of government studies were conducted on the lethal effectiveness of infantry weapons. The basic SPIW concept was an individual infantry weapon that fired both flechettes and grenades. The U.S. Springfield Armory along with Harrington & Richardson, Aircraft Armament Inc. (AAI) and Winchester were involved in developing a satisfactory weapon. The requirements set for the proposed SPIW included a 60-round magazine for the flechette ammunition and a multi-shot 40mm grenade launcher. There was a maximum weight limit of 10 pounds loaded with 60 flechette rounds and three grenades. Development of a suitable SPIW was deemed to be unrealistic, and the program was terminated in 1968.

The realization that the SPIW program was heading for failure came as welcome news for Colt. The war in Vietnam was escalating, and more M16 rifles would be needed to equip the growing number of U.S. military personnel being assigned there.

The XM16E1 to the M16A1

The XM16E1 was the first model of the Colt/ArmaLite M16 rifle that was purchased in large quantities by the U.S. government. The M16 would become infamous during the rifle’s service during the Vietnam War. The problems experienced with the XM16E1 were the result of not one, but a compilation of missteps. The problems with the weapon resulted in a Congressional Investigation, the Ichord Committee, in 1967.

Plating the Barrel Chambers

One of the primary reasons for the M16 rifle’s early failure was being purchased “off the shelf” with little or no initial engineering study by the Ordnance Corps, who were quite dissatisfied with the adoption of a rifle from outside the traditional ordnance system. A major contributing factor was a failure to chromium plate the barrel chambers. During fighting in the Pacific Theatre during World War II, it was discovered how a humid climate contributed to rapid barrel corrosion, which resulted in failure to extract cartridge cases stuck in the chamber. As a result, all production M14 rifles had chromium barrel chambers and bores. So why didn’t the original AR-15 / M16 rifles have chromium-lined barrels? Because people in government, who knew little or nothing about small arms, were making decisions based on cost. The infamous quote, “If the rifle needed a chrome chamber, [Gene] Stoner would have designed it that way.”

Ball Powder

Originally the AR-15 / M16 rifle was designed around cartridges loaded with DuPont IMR® (Improved Military Rifle) gun powder. A decision was made to load the 5.56mm rounds with Olin-Mathieson 846 ball powder. This was done with no testing for any effects the change might have on the weapon’s gas impingement system. Ball powder burns faster than IMR powder; this resulted in a higher port pressure, which in turn increased the full-automatic cyclic rate far beyond the rifle’s design limitations. A number of 5.56mm cartridges loaded with ball powder were issued to the troops in Vietnam, and the result was disastrous.

Other transitional enhancements were made to the XM16E1 to create the M16A1 rifle, solving the reliability problems with the weapon:

- A new, redesigned buffer

- Chromium-plated barrel chambers and cleaning kits

- “Bird cage” flash hider, replacing the 3-prong type

- Chromed bolt carrier replaced by a Parkerized bolt carrier with chromium internal surfaces

- New firing pin retainer

- Redesigned bolt catch to resist breakage

- Original gas tube replaced by one made of corrosion-resistant stainless steel

- Receiver-raised “fence” to protect magazine release button from accidental ejection of the magazine

- New buttstock designed with hollow section to contain a cleaning kit, including trapdoor to access the kit

- Introduction of a 30-round magazine during 1969

By 1967, the M16 was a reliable weapon and type-classified as the M16A1 rifle. To keep up with demand, Harrington & Richardson and the Hydra-Matic Division of General Motors were awarded contracts to manufacture M16A1 rifles. The M16A1 would serve as the Standard A rifle until being phased out by the M16A2. The product-improved M16A2 was adopted by the Marine Corps in 1983 and the Army in 1986.

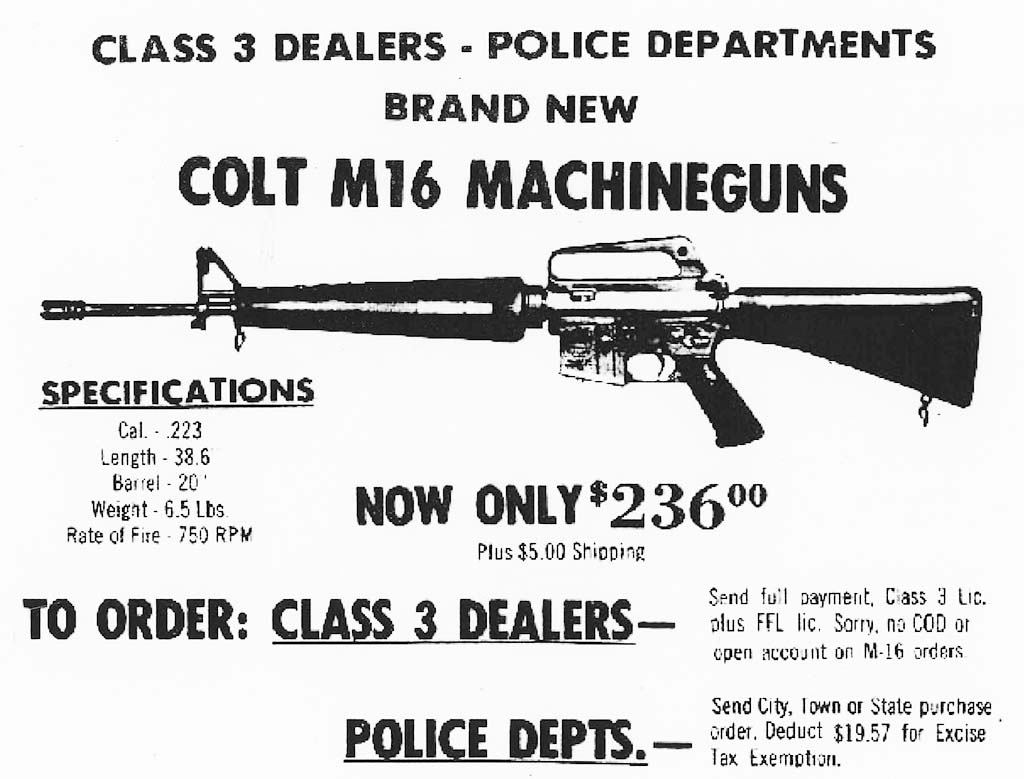

Civilian M16 Rifles

Fortunately for NFA collectors and enthusiasts, a fair number of M16 rifles were registered and transferable. Colt’s policy during the 1980s was that each Class III dealer could order one M16A1 rifle and one carbine. Colt specified that to reorder the rifles dealers would have to provide proof that the guns were sold to a law enforcement agency. As a result, the M16s that were offered to individuals were sold at a premium. Along with the commercial Colt M16A1 models, a few “U.S. Gov’t Property”-marked M16s made by Colt, H&R and GM’s Hydra-Matic Division were registered during the 1968 amnesty. When offered for sale, they often commanded a premium price. In addition to amnesty-registered U.S. government property-marked rifles, the Harrington & Richardson® (H&R®) Corporation sold a number of their Vietnam-era contract U.S.-marked M16A1s during an asset reduction sale in 1985. There have been 66 new H&R M16A1 rifles documented from that sale, along with a lesser number of M14 rifles. Also, occasionally available are the select-fire Colt model 614 rifles marked “AR-15.” A few M16A2 models also were registered prior to the May 1986 ruling ending the registration of transferable machine guns.

A few military M16 receivers that were functionally destroyed by shearing once through the trigger area, were painstakingly welded back together and registered. There was an article in the July 1986 issue of the old Firepower magazine by John Norrell describing the process. Unfortunately, by the time the article was published in July, it was no longer possible to register a transferable machine gun.

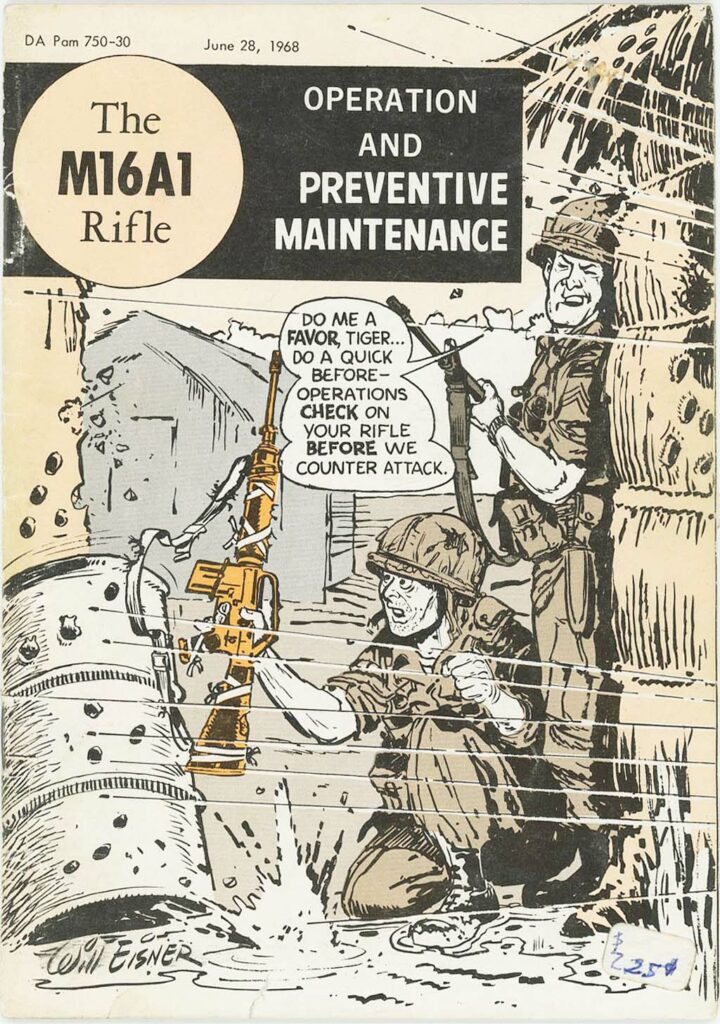

“Why do you keep your M16 rifle clean inside and out and lubed with LSA? Because you bet your life on it!!”

PS Magazine used cartoon drawings, featuring the alluring “Miss Connie Rodd” to encourage young troops to read it.

Conversions of Semi-Automatics

In addition to the factory select-fire M16s, prior to 1986, it was legal to convert semi-automatic AR-15-type rifles to select-fire after paying a $200.00 federal tax and receiving approval from the NFA branch of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. In addition to receivers, there were “drop-in” “auto-sears” and “lightening links” registered to convert semi-autos to full-auto. Today the drop-in devices are often more expensive than a factory M16 rifle. The attraction, that justifies the five-figure price to many, is the device itself is a “machine gun” and can be legally used in any semi-automatic AR-15-type rifle.

In addition to Colt-made SP1 AR-15s, a number of pre-1986 conversions were done to other manufacturers’ AR-15-type rifles. A few of those companies included Frankford Arsenal, Sendra Corp., SGW-Olympic Arms and the Essential Arms (EA) Company.

Recommended Reading

The Black Rifle, Volume I by Christopher R. Bartocci, R. Blake Stevens and Edward C. Ezell

The U.S. M14 Rifle: The Last Steel Warrior, Second Edition by Frank Iannamico

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V25N3 (March 2021) |