Many assume a firearm’s safety mechanism will reliably prevent an accidental discharge. However, that’s a risky assumption because safeties come in varying degrees of safe. How safe really depends upon the safety mechanisms’ design, and safety designs vary as much as gun models and manufacturers. Understanding your gun’s operation and safety mechanism is a must, especially if you intend to carry it or keep it in a ready status for home defense with a round chambered. There are three golden rules when it comes to firearms’ safeties: not all safeties are created equal, safeties are a mechanical device – like any other mechanical device, they wear out and fail, and ON Safe doesn’t necessarily mean safe; never trust your life or anyone else’s to a safety. Always observe firearm safety protocols.

Firearms safeties may be best understood if they’re divided into two categories – manual safeties and automatic safeties. Manual safeties (sometimes called “active safeties”) typically require the shooter to manually operate a lever, switch, or button from an “off” position to an “on” position or vice versa. Comparatively, automatic safeties are internal safeties (sometimes called “passive safeties”) that operate without manual manipulation by the shooter.

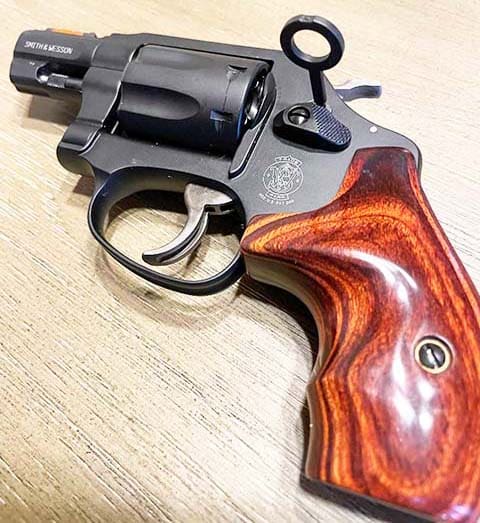

There is another safety device category that is external to the gun itself – the external safety. This category includes bore locks, trigger locks and gun safes. In the late 1990s the ATF pressured handgun manufacturers to include integral locking mechanisms on handguns that could only be unlocked by inserting a special key into the gun at exactly the right place before the gun could be fired. That didn’t bode well with common sense and the gun owner community because it added yet another step to making a gun ready to fire in an emergency scenario. Fortunately, only a few manufacturers like Smith & Wesson capitulated to political and media pressure by adding integrally designed key locks to their handgun line. This entire safety device category is obviously intended for secure firearms storage and theft deterrence and does not apply to firearms for ready use or carry. For the purposes of this article, these will not be further discussed.

Manual Safety

The most common gun safety is the manual safety. It consists of a switch, button or lever that, when manually set to the “safe” position, prevents the firearm from firing. While seemingly straight forward, the design mechanics involved in manual safeties are as different as the firearms they serve. Of the many designs, most conform to some variation of two basic designs. The first employs a block or latch that prevents the trigger and/or firing mechanism from moving. The second type mechanically disconnects the trigger from the gun’s firing mechanism. There are exceptions to the rule. For example, in a conscious effort to keep the firearm in a higher state of readiness many “double-action” firearms (like revolvers and some pistols) do not have manual safeties. The thinking is the double-action, longer-harder trigger pull to cock and fire provides adequate safety. Whether that’s the case, it’s left to the shooter to determine. That’s why many carry their revolvers on an empty chamber or do not chamber a round in a double-action, semi-automatic pistol for fear of accidental discharge. Of course, carrying a gun for the purpose of self-defense without a chambered round is akin to carrying an empty canteen into the desert in case you find water. It’s illogical.

Grip Safety

There are grip safeties, as well. The classic Colt .45 M1911 design is a prime example of a semi-automatic handgun with a grip safety, while Springfield Armory’s XD pistol and the Uzi submachine gun are other notable examples with a grip safety. A grip safety is a lever or other grip-depressible device positioned on the grip of a firearm (usually the rear strap area) that can only be actuated as a natural consequence of gripping the firearm in the proper firing position. Grip safeties function much like a manual safety, but they are momentary, and only deactivate while the shooter maintains his squeezing hold on the pistol grip. Once the shooter releases his grip, the safety is immediately re-engaged.

Integrated Trigger Safeties

Like grip safeties, trigger safeties are de-activated as a natural consequence of properly holding and pulling the trigger but are otherwise engaged, providing a margin of safety. First used in the 1897 Iver Johnson Second Model Safety Hammerless revolver, there are two independent parts that comprise a trigger safety – a trigger and a small blade-like spring-tensioned lever protruding forward from inside the trigger’s lower half. This lever, when fully depressed by a trigger finger on each trigger pull, disengages a trigger locking mechanism that allows the main trigger body to move rearward. The lever does not disengage the trigger lock without intentional depression.

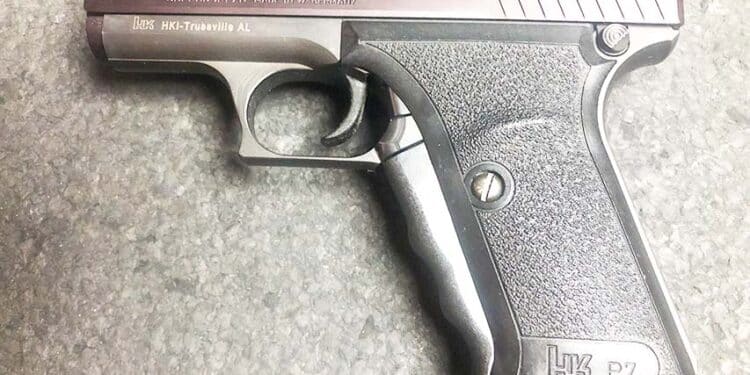

Squeeze-Cocker

During the mid-1970s, Heckler & Koch debuted a unique squeeze-cocker safety in their Model P-7 pistol line. Without a doubt, this was a revolutionary pistol safety concept because the pistol was only cocked and ready to fire when a full, grip-length lever located on the front edge of the pistol grip was fully depressed by the shooter. When the shooter released his grip, the P-7 was immediately decocked. The design prevented the single-action trigger alone from cocking the firearm and so, the P-7 would not fire unless the grip was fully squeezed rearward to its stopping point. There were several other ways the P-7 could be fired. The trigger could be pulled first and then when the grip was subsequently squeezed, cocking the gun, the gun would fire. It could also be fired if the grip was squeezed and the trigger was pulled simultaneously. The key to all the P-7’s firing alternatives was fully squeezing the grip cocking lever. The P-7 enjoyed limited popularity among U.S. hand gunners because a quickdraw and fire sequence was impossible. P-7 production stopped in the late 1990s because of a dwindling market. Nonetheless, the concept was out of the box thinking that could have been further refined for application on other types of firearms.

Decocker

Traditionally, semi-automatic single action/double-action (SA/DA) pistols are designed to be carried with the hammer down on a chambered round, with or without a manual safety engaged. With the hammer down, the pistol is uncocked, and it is considered safe. In this state, pulling the double-action trigger both cocks and fires the firearm. On the other hand, the double action trigger pull is both longer and heavier (measured in pounds) than the single action trigger pull which simply releases an already cocked hammer.

Therefore, discharging the firearm, or manually cycling the slide to chamber the first round will both load a round into the firing chamber and cock the hammer in the single-action mode. This makes it necessary to un-cock the hammer to return the pistol to its safe state. On hammer-fired pistols, this is accomplished by holding the hammer spur with the thumb while carefully pulling the trigger, then slowly lowering the hammer down onto the firing pin. This procedure has the inherent risk of accidental discharge, especially if one’s thumb slips off the hammer during the process of uncocking. It takes practice.

Comparatively, striker-fired pistols, do not have a hammer. This means the only way to return the trigger to its longer double action pull is by means of a decocker mechanism that is purposely designed into the gun. The decocker mechanism safely releases the striker’s spring tension without allowing the firing pin to travel.

Some hammer-fired pistols also employ a decocker which consists of a physical firing pin block that physically prevents the hammer from contacting the firing pin as it falls. The actual process of decocking is done by rotating the decocking lever to the decocked position. The decocking lever is usually ambidextrous and located on the rear of the frame or slide for thumb manipulation. A decocker eliminates the need to pull the trigger and control the fall of the hammer. While using a decocker seems straight forward, they are not foolproof. Always keep your gun muzzle pointed in a safe direction while decocking.

Remarkably, the decocker is not new to firearms. The earliest use of a single action decocker can be traced back to 1932 where it debuted on the Polish-built Radom Vis wz. 35. The Radom pistol was based on John Browning’s M1911 design, and its design purpose was to provide horse-mounted cavalry soldiers a pistol that could be safely decocked and holstered using one hand. The Radom decocker led to a more advanced, yet simpler, two-way decock-safety combination consisting of a manual safety switch and decocking. This single lever both engaged the safety and decocked the pistol. In 1938, SIG Sauer followed with its cocking/decocking lever in the Sauer 38H and has continued to feature decocking levers in its line of pistols to this day. Walther incorporated the decocking feature into its famous “PP” models and Beretta later used it on the Beretta 92 (M9) models.

Not to be outdone, Heckler & Koch equipped their line of pistols with a unique “three-way” decocking safety system which decocked the pistol by pushing down on the safety lever from the “Fire” setting or engaged the safety (even on a cocked firearm) by pushing the lever upwards. In 2007 Ruger debuted the “decock-only” variants of its P-series pistols and has offered the decocking safety on these pistols ever since. As should be apparent, the decocking-safety, in its many forms, has become commonplace because it works reliably.

Drop Safety / Firing Pin Block

The oldest form of drop safety is the safety notch (many times referred to as “half-cock.”) It was used on most black powder 19th Century-era rifles and pistols and transitioned to rifles and single-action revolvers manufactured before the invention of the hammer block. Numerous reproduction models of bygone era rifles and pistols are still equipped with a safety notch. The safety notch is nothing more than a relief cut made in the tumbler at the base of the hammer that allows the trigger sear to catch and hold the hammer a short distance away from the cap / cartridge primer. The safety notch is engaged by partially cocking the hammer a short distance from the firing pin or primer. Once the safety notch is engaged, the hammer is locked to any forward motion without first manually cocking the hammer before pulling the trigger. The safety notch, when engaged, acts as a primary safety by effectively preventing the hammer from any forward travel towards the firing pin should the weapon be dropped. More importantly, in scenarios where dropping a weapon jarred the trigger sear loose (the trigger releases the hammer from the drop shock of inertia), it provides a margin of safety by “catching” a falling hammer when the trigger has not been pulled.

There is a downside to the safety notch. Safety notch-style safeties are subject to wear and breakage which often results in unintentional discharges. Secondly, while not a complicated process, placing the hammer into the half-cock position is an active feature that the shooter must consciously engage. That process requires a certain amount of operator familiarity and manual dexterity to prevent accidental discharges.

To make it appear they were in control of the situation, Congress stepped in following a rash of political assassinations in the 1960’s timeframe. Drop test requirements for imported guns were introduced along with the Federal Gun Control Act of 1968. The new law’s stated purpose was to provide a basis for import denial of cheaply built firearms that could inadvertently fire if they were dropped or roughly handled. Most firearm designs prior to 1968 had the uncocked firing pin being held idle by the firing pin spring above a chambered round. This meant the inertia from a vertical drop that was in line with the firing pin would drive the firing pin forward onto the primer of a chambered cartridge, causing the gun to fire. It also meant that the anti-gun community now had a raison d’etre they could use to regulate gun imports, while it further provided a liability premise for lawsuits. Unfriendly gun states like California immediately jumped on this bandwagon by requiring all new guns imported into California to have some form of positive drop safety built into them.

The gun manufacturers responded by engineering passive drop safeties into their new firearms. The best way to picture these passive safety designs is to visualize the firing pin being cut in its middle and physically separated by a wedge-like block called a “firing pin block” that is held in place by a small spring that is attached to the trigger mechanism. As the trigger is pulled, the wedge is withdrawn from the firing pin halves and the firing pin is made whole again so the gun can fire. As the trigger pull is relaxed, the wedge again lifts to physically block the firing pin mechanism. Therefore, drop safeties provide a physical obstacle to the operation of the firing mechanism. This block is only removed when the trigger is pulled so that the firearm cannot discharge if dropped.

While government-required drop safeties seem reasonable, there is a downside and that’s firing reliability. There are some drop safety designs that will only allow the gun to fire if it’s being held straight and level. That means your gun may not reliably fire if you’re engaging a target that requires the firearm be held in a vertical orientation (think aiming down from a rooftop, up a stairwell, etc.) or while shooting upside down, laying on your back (think extreme situations, not Hollywood). So, for those who bet their lives on gun reliability, drop safeties are not necessarily desirable.

Hammer Block

Like a firing pin block, a hammer block consists of a block built into the action that physically prevents the hammer from contacting the firing pin when down (at rest) in the uncocked position. Much like the firing pin block, the hammer block is withdrawn as the trigger is pulled.

Transfer Bar

Transfer bars are used in some exposed hammer-fired revolver and rifle designs. In most designs the transfer bar rotates out-of-line with the hammer’s travel, making it physically impossible for the hammer to contact the firing pin. When the trigger is pulled, the transfer bar rotates into alignment with the firing pin. The hammer falls, striking the transfer bar at its firing point, which transfers the hammer strike to a firing pin-like spur that strikes the cartridge primer and fires the gun. Like the firing pin block, the transfer bar provides a similar level of drop safety.

Bolt Interlocks and Trigger Disconnects

Some form of bolt interlocks and/or trigger disconnects are used on most all modern repeating action firearms to include bolt, pump and lever-action shotguns and rifles. A bolt interlock works by disengaging (or blocking) the trigger when the bolt is not in full battery (fully closed and fully locked). The trigger disconnect prevents the gun from firing until the bolt is fully locked and thus prevents out-of-battery “slam fire” malfunctions. These mostly result from worn out trigger catch mechanisms that allow the hammer to follow the bolt or bolt carrier group forward as it closes. That’s why modern self-loading firearms require a separate trigger reset and pull to fire each successive cartridge. Even though interlocks and trigger disconnects help prevent misfires when the firearm is not in full battery, they are not considered safeties because they can easily fail from excessive wear, rust, or accumulated dirt. Keep your weapon clean, lubricated and inspect for wear every time you clean it.

Magazine Disconnects

The Browning Hi-Power pistol was one of the first production handguns equipped with a magazine disconnect. In 2006, California passed legislation requiring magazine disconnects on all new handgun designs sold in the state beginning January 1, 2007 which resulted in their widespread proliferation. A magazine disconnect prevents the gun from firing if the magazine is withdrawn or not fully locked into place even if there is a round in the chamber. It works by means of a mechanism that engages an internal safety like a firing-pin block or trigger disconnect when the magazine is not locked in place.

Like any automatic safety, there are magazine disconnect pros and cons. Yes, the gun cannot fire without a properly installed magazine, and an accidental discharge can be prevented with the magazine removed. However, the disconnect mechanism, itself, adds tension to the trigger mechanism components and that often makes the trigger pull unpredictable or heavy. A real safety concern, especially on older guns, is that spring fatigue and/or rust can lead to magazine disconnect failure. When it does, it will most likely happen when the gun is in the “fire” mode without giving the shooter any indication of its failure; a circumstance that can be lethal.

An additional safety argument against a magazine disconnect is that the user may eject his magazine when unloading his pistol, then reinsert an empty magazine into the magazine well to dry fire the gun for storage. Even though the magazine is empty, once it’s inserted, the disconnect firing system becomes reactivated. That means if a live round was inadvertently left in the chamber, the gun will fire. The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) stated that an “obvious concern with magazine disconnect features is that determining whether the gun is safe becomes linked to the presence of the magazine as opposed to actually checking the gun, opening the action, and making sure it is unloaded.” For the reasons stated above, many shooters deactivate their gun’s magazine disconnect feature and rely instead on sound firearm handling safety protocols.

While not a safety, per se’, the loaded chamber indicator is found on many modern semi-automatic handguns. Its purpose is to provide the shooter a visual cue that a round is chambered. Depending on the manufacturer and model of the pistol, it may come in the form of a small protruding button or bar that pops up somewhere behind the slide’s ejector port to indicate the presence of a chambered round. Other designs consist of a small cut away section along the top or side edge of the bolt face that allows the shooter to see the brass cartridge rim of a chambered cartridge. Regardless, one should never bet their life on a loaded chamber indicator. There is no better way to positively confirm that a round is chambered (or not) and that is to do a simple “press check”. This is accomplished by partially pulling the slide back and visually sighting the rear of the chamber for the presence of a cartridge, and then easing the slide forward into battery.

Why Can’t the Firearms Industry Agree on the Use of a Common Safety Mecanism?

The answer is simple. Safeties are as varied as the gun models themselves. Different operating systems and trigger mechanisms require different safeties. What works for one design may not work for another. Most of all, we must not confuse what is theoretically possible with what is practically feasible. Trust and belief are different. Trust is based upon past performance. Belief is divine. Trusting a firearm safety’s reliability and believing safeties work both require physical verification. The bottom line: Never trust or believe any safety is 100% safe. Treat all firearms as though they’re loaded and ready to fire.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V26N6 (JUNE/JULY 2022) |