By Robert Bruce

“The employment of flame projectors as tactical weapons was a concept that appealed to the Western Front belligerents, perhaps not as a key to the deadlock but as a nonetheless valuable device. The Germans had first used a portable apparatus for projecting flaming oil in June 1915. The French soon developed a similar apparatus, and shortly thereafter Germans, French, and British each developed small portable, as well as large, semi fixed projectors. The value of flame at the time was principally psychological – the fiery spurt of burning oil, the roar of the flame, and billowing clouds of black smoke had a terrifying effect on troops in the trenches.” From THE CHEMICAL WARFARE SERVICE: CHEMICALS IN COMBAT, United States Army in World War II series, The Technical Services, Office of the Chief of Military History.

Writing well after the end of World Wars I and II, the authors of this authoritative volume in the official history of the U.S. Army had the distinct advantage of hindsight. Not just from the Twentieth Century’s two earth-shattering conflicts, but also many previous centuries of documetation describing the use of flame weaponry.

While most recent recountings correctly include note of ancient Chinese incendiaries and “Greek Fire” dating back to hundreds of years before the birth of Christ, it is not unreasonable to speculate that warring tribes of prehistoric times used their mastery of fire in battle. This ranged, some scholars speculate, from the intimate form of torches thrust at arm’s length to the setting of wind-blown wildfires in dry grasslands to disperse enemies and destroy their encampments.

Because both friend and foe were well acquainted with the painful, crippling and even deadly results of burns from campfires and such, the combat utility of even primitive flame weaponry in any form would enjo an added benefit “that was principally psychological.”

World at War

As the focus of this article is on practical, man portable flame weapons, we’ll fast-forward to 1911. Here we find the first of these, credited to one Richard Fiedler (sometimes Fedler), brought into service by the German Kaiser with specialist units of his Deutsches Heer (Imperial German Army).

Fiedler’s Flammenwerfer (flame thrower) consisted of a single large, heavy tank carried like a backpack, containing both flammable oil and pressurized propellant. A long hose attached to an equally long pipe style “gun” was used to ignite and direct the burning stream.

Some accounts say the Kaiser wasted little time in putting these to use, citing limited action against the French in October 1914, just two months after the outbreak of what would soon become known as the Great World War. By June and July the following year, German flamethrower assaults across the trenches against British and French units had intensified, reportedly causing defenders to panic and retreat in terror.

While the heavy and awkward apparatus was theoretically capable of being carried by one necessarily very strong man, tactical doctrine wisely called for multi-man teams. A very brave flame gunner was out front, closely trailed by a stalwart tank carrier plus additional riflemen/grenadiers for much needed protection.

Because flamethrower operators were understandably the object of intense hatred and vigorous defensive actions by their intended victims, this necessarily practical formation would be carried forward in other armies and subsequent conflicts.

British and French forces quickly developed and fielded their own flamethrowers – man portable, emplaced and tank borne – adding even more horror to the aerial attacks, artillery, machine guns, and poison gas of trench warfare on the Western Front.

World War II

In the years between the end of WWI in 1918 and what is seen as the formal beginning of WWII in 1939, improved backpack flamethrowers were employed by most all major powers and used in various interwar actions by the Japanese in Manchuria, Italians in Ethiopia and when the Germans invaded Poland.

Most all that is, except America, correctly termed the “sleeping giant” by Japanese Admiral Yamamoto, architect of the devastating sneak attack on Pearl Harbor. When Uncle Sam entered the war in December 1941, his gross deficiencies in the full spectrum of war fighting implements included only a handful of two types of experimental flamethrowers, both vastly inferior to those in use by the Japanese and Germans.

“The Kincaid Co. of New York manufactured a few of the first experimental models, designated as E1, in the autumn of 1940. This and all subsequent models consisted of four main components: a storage system for fuel, a storage system for compressed gas, a flame gun and an igniter.” THE CHEMICAL WARFARE SERVICE: FROM LABORATORY TO FIELD, United States Army in World War II series, The Technical Services, Office of the Chief of Military History.

A 70 pound, single tank model similar to the WW I German version, the E1 had numerous serious flaws that prompted the Chemical Warfare Service to go back to Kincaid with updated specifications, resulting in an improved version, delivered in March 1941.

As detailed in the book cited immediately above (CWS:LtoF), “Now the fuel and compressed nitrogen were stored in separate reservoirs, a feature retained in all future models. The gun, the ignition system, and the valves were all improved. The weapon weighed 28 pounds empty and 57 pounds loaded.”

The E1R1 had improved range and burn time but still needed work. It was too heavy, prone to breakage and its control valves were awkwardly positioned. Also, the original E1’s problematic ignition system, mounted on the flame gun and consisting of a long slim tank of compressed hydrogen gas sparked by a battery, was retained in this and the next two models.

However, being the only flamethrower in hand, it was sent off to training camps and some of these deployed with units to the battle front. On 8 December 1942 in Papua, New Guinea, one of these E1R1 units marked the first U.S. use of a flamethrower in combat with particularly pitiful results, recounted in CWS:LtoF: “Corporal Wilbur G. Tirrell crawled through the underbrush to a spot some thirty feet from a Japanese emplacement. He stepped into the open and fired his flame thrower. The flaming oil dribbled fifteen feet or so, setting the grass on fire. Again and again, Corporal Tirrell tried to reach the bunker, but the flame would not carry. Finally, a Japanese bullet glanced off his helmet, knocking him unconscious.”

Unfortunately for Tirrell, he didn’t have the newest “new and improved” model that had started rolling off the production lines in March 1942. Similar in appearance to its predecessor, this was the M1 with sturdier components and ignition improved by additional attempts at waterproofing.

15 January 1943 marked the initial use of the M1, successfully employed by soldiers and Marines on Guadalcanal. With demonstrated effectiveness beyond the capabilities of any other weapon, the flamethrower soon became indispensable in the ground war against increasingly elaborate Japanese fortifications.

M1A1

Up to this point the range and on-target effectiveness of U.S. flamethrowers were limited by the physical properties of ordinary gasoline. Increasing system pressure to drive the fuel stream only caused the spray to “atomize” and burn out more quickly. Also, this airy, short duration burn limits casualty producing effects.

“The weapon that replaced the M1 came about as a result of the invention of napalm, developed initially to thicken gasoline fillings in incendiary bombs. The CWS (Chemical Warfare Service) tested thickened gasoline in flame throwers and found that the range was greater than with ordinary gasoline… thickened fuel flew through the air in a compact stream that would ricochet into portholes and stick to flat surfaces… The M1A1 could expel thick fuel two or three times as far as the old model.” (CWS:LtoF)

The napalm-pumping M1A1 resulted from minimal changes to the M1, principally modifications to the fuel system, pressure regulator, valves, and flame gun. Thousands of this model were quickly fielded, reaching the Mediterranean theater in June 1943 and South Pacific in July.

Despite better waterproofing and improvements to the battery sparked hydrogen ignition system there were still failures to ignite, too often forcing GIs to continue to rely on backup methods like ordinary matches.

Copying the Japanese

“The CWS turned out a weapon, E3, with a streamlined gun, improved valves, a comfortable pack similar to the standard Quartermaster pack-board used for carrying mortar shells and other ammunition, and a cartridge type ignition. The latter was similar to a revolver. It held six cartridges, each filled with a pyrotechnic mixture. When the operator pressed the trigger a shower of sparks erupted from the cartridge and ignited the fuel.” (CWS:LtoF)

Interestingly, the E3’s cartridge ignition system that is such an important improvement in reliability of what became officially standardized and adopted as the M2-2 (M2 tank assembly with improved M2 flame gun) was based on that of the Japanese Model 93 and Model 100 flamethrowers. Examples had been captured early in 1942 and sent back to the U.S. for test and evaluation.

The enemy‘s reloadable, revolver-like ignition system with its ten blank cartridges was modified to a pre-loaded six shot throwaway plastic cylinder featuring significantly better waterproofing and intensely burning magnesium filler.

The M2-2 was adopted as standard in March 1944. First combat use came four months later in the operation to secure the island of Guam and first issue to units fighting the Germans came in March 1945. By the end of the war more than 24,500 were manufactured, more than all earlier models combined.

Little Shots and Big Shots

In addition to grunt-humped flamethrowers, allied and axis forces developed and fielded stand-alone devices for defensive emplacements as well as large, powerful, long range, long duration add-ons for tanks. The latter spared many a ground pounding GI and his buddies from the dangerous and deadly chore of close range attacks on bunkers, pillboxes and caves.

And while the Germans introduced the Eintossflammenwerfer 46, a simple, disposable, singleshot weapon for assault troops and paratroopers, an American version still wasn’t finalized when the war ended in 1945.

“Blowtorch and Corkscrew”

After nearly four years of intense fighting, particularly in the Pacific, the Army and Marine Corps had perfected tactics for dealing with the enemy’s increasingly sophisticated bunkers, pillboxes, caves and tunnels. Coordinated use of demolition and flame weapons of standard and novel forms in this nasty business reached its zenith in the fight to take the fanatically defended Japanese homeland island of Okinawa.

“Each small action, a desperate adventure in close combat, usually ended in bitter hand-to-hand fighting to drive the enemy from his positions and there to hold the gains made. In these close-quarters grenade, bayonet, and knife fights, the Japanese frequently placed indiscriminate mortar fire on the melee. The normal infantry technique in assaults on caves and pillboxes involved the coordinated action of infantry-demolition teams, supported by direct-fire weapons, including tanks and flame throwers. Cave positions were frequently neutralized by sealing the entrances.

“In some instances Tenth Army divisional engineers employed a 1,000-gallon water distributor and from 200 to 300 feet of hose to pump gasoline into the caves. Using as much as 100 gallons for a single demolition, they set off the explosion with tracer bullets or phosphorus grenades. The resulting blast not only burned out a cave but produced a multiple seal. The complete destruction of the interconnected cave positions sometimes took days.

“The tank-infantry team waged the battle. But in the end it was frequently flame and demolition that destroyed the Japanese in their strongholds. General (Simon B.) Buckner, with an apt sense for metaphor, called this the ‘blowtorch and corkscrew’ method. Liquid flame was the blowtorch; explosives, the corkscrew.” (UNITED STATES ARMY IN WORLD WAR II, The War in the Pacific, OKINAWA: THE LAST BATTLE. Center of Military History, U.S. Army)

Postwar Developments

Modest upgrades of America’s M2-2 devices continued in service through the Korean War and – particularly with the traditionally conservative and thrifty Marine Corps – in the early years of the Vietnam War buildup. Experimentation during this time produced a series of “new and improved” models including the M2A1-2, M2A1-7 and M9A1-7. But all of these were essentially the same in form and function as their WW2 predecessors. Not as much so was the Soviet LPO-50, the flamethrower in use by America’s primary adversaries at the time that was copied and manufactured in great quantities by the Red Chinese.

Instead of propelling its thickened fuel with conventional gas-pressurized means, the LPO-50 uses special high powered blank cartridges to blow each of three individual fuel tanks in turn. One of three other blanks at the muzzle of the weapon’s rifle-like flame gun is fired simultaneously to ignite the continuous 2-3 second fuel stream.

Two big advantages are simplicity in preparation and use as well as impressive 70 meter range. On the other hand, the unit recoils ferociously, doesn’t shut off when the trigger is released and – like conventional models – still takes considerable time to reload and refill.

The first dramatic departure from traditional “squirt and burn” flame weapons was the rocket-firing U.S. XM191 Multi-Shot Portable Flamethrower, composed of the reloadable four-barrel XM202 Launcher and XM72 Incendiary Clip.

An Army Chemical Center news release from September 1970 provides a useful overview: “The conventional Army flamethrower weighs nearly 70 pounds fully loaded, is accurate only to a range of 50 meters, has a total firing time of nine seconds, and calls for elaborate reloading procedures. By comparison, the XM191 weighs only 27 pounds fully loaded, has deadly accuracy to 200 meters, and can be fired as long as it has ammunition available. The XM191 uses four rockets which are fired consecutively. The rocket warhead is filled with a substance that ignites instantly when exposed to fresh air.”

The substance in the warheads is not napalm as has been repeatedly and erroneously stated. Instead, it is TPA, shorthand for triethylaluminum, thickened with polyisobutylene. It sticks to what it hits, ignites spontaneously in air and burns at a fearsome 2,000 degrees.

Successfully combat tested in the latter part of the Vietnam War, it was later type standardized as the M202. It completely replaced conventional flamethrowers in U.S. service in 1978 when official squeamishness over their use resulted in removal from the inventory. Interestingly, this apparent aversion didn’t extend to continued use of napalm, white phosphorous, or to the M202’s incendiary rockets.

Although unlikely to have been constrained by public opinion, the Soviet Union took this same track, discarding the LPO-50 for the RPO series of Infantry Rocket Flamethrowers.

Thermobarics

As if mere burning and suffocating aren’t horrible enough, the inevitable quest for improvement in efficient lethality has led to development of “thermobaric” explosives – particularly for use in the caves of mountainous Afghanistan. The following grisly explanation is provided by the Australian Ministry of Defense: “Explosives used in thermobaric weapons are generally oxygen-deficient; additional oxygen from the air is required to achieve complete combustion of the charge. Only part of the energy is released during the initial detonation phase, which generates high levels of fuel-rich products that undergo “afterburning” when mixed with the shock-heated air. The energy released through after-burning and combustion lengthens the duration of blast overpressure and increases the fireball.”

A rogue’s gallery of thermobaric weaponry and warheads has emerged including the Russian RPO Shmel-M, the Red Chinese WPF 2004 rocket for the ubiquitous RPG-7, the U.S. SMAW-NE round, and even a little 40mm super fire grenade for M203 type launchers. All have proven so effective in combat use that many more variants are on the way.

Flamethrower Live Fire

While spectacularly scary, flamethrowers are not restricted under federal law. There are a number of places where WW2 style flamethrowers are demonstrated, but exceedingly rare is the opportunity for regular folks to strap one on and squirt some hellfire.

Perhaps the best known flamethrowing venue is Knob Creek Gun Range’s semiannual Machine Gun Shoot, typically held on the second weekend of April and October. (www.knobcreekrange.com)

Located in West Point, Kentucky, some twenty miles south of Louisville, the event features not only a firing line full of an amazing variety of exotic full autos, but also a 900 table Military Gun Show, colorful shooting competitions, and machine gun and flamethrower rentals – closely supervised, of course.

Now, practical concerns dictate that nearly all public demos, including those at “The Creek,” necessitate flamethrowers modified to be simply, cheaply and reliably ignited by propane torches rather than military issue pyrotechnic cylinders. This is because original cylinders are nearly impossible to find and, even if painstakingly and skillfully reloaded, require flame guns with functioning striker mechanisms.

The bottom line is there’s just too much trouble involved for this kind of authentic touch that most folks wouldn’t be aware of or don’t much care about anyway.

But for those who have closely observed flamethrower operations in wartime newsreels, the telltale shower of sparks spewing from the muzzle of the gun group is mandatory to accurately replicate the real thing in combat action.

Meet the Real Thing

A quest for authenticity is what drew us to Solomons, Maryland in August 2000 for a commemoration of the 58th anniversary of the U.S. invasion of Japanese-held Guadalcanal. This and subsequent “island hopping” landings were launched by many of the Marines and Sailors who had intensively prepared at Solomons and other Chesapeake Bay beaches near the U.S. Naval Amphibious Training Base in Calvert County.

A reliable source guaranteed the opportunity to observe an impressive WW2 living history display by the renowned U.S. Marine Corps Historical Company (www.usmchc.org), encamped on the grounds of the Calvert Marine Museum. And for icing on the cake, there were assurances that we’d meet flamethrower maestro Larry McLean and photograph in detail his meticulously correct WW2 vintage M2-2 flamethrower – complete with original, military surplus ignition cylinders that would be sacrificed for good cause in several live fire demonstrations for the public.

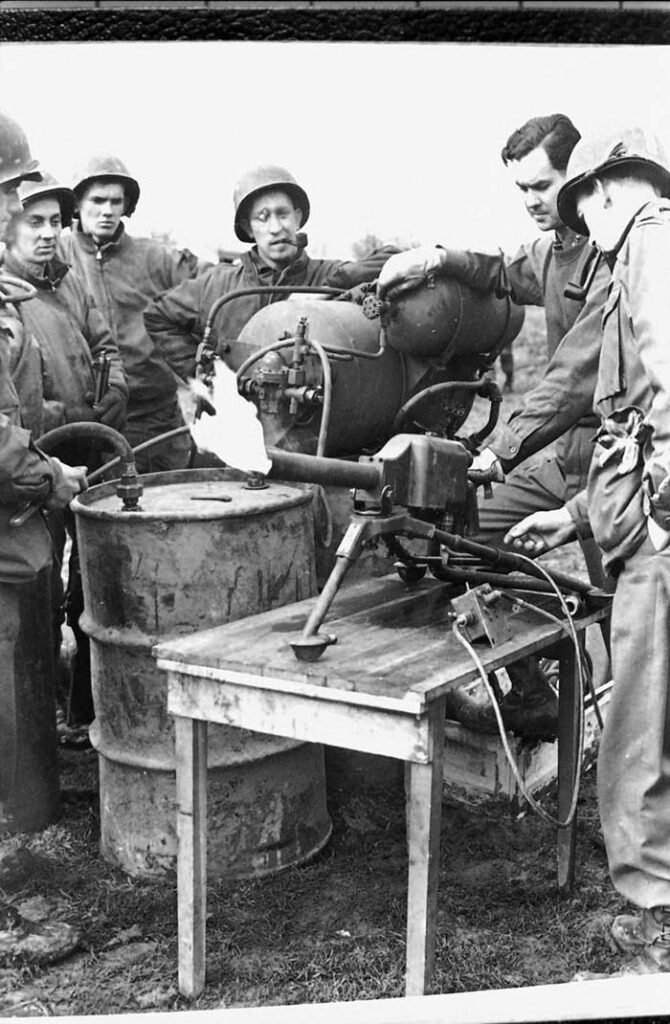

McLean, a friendly fellow who graciously consented to cooperate with our mission, quickly proved to be a particularly dedicated flamethrower enthusiast and restorer, ready to explain all aspects of his M2-2 as he prepared it for show time.

The weapon system itself was housed in an original WW2 wooden carrying chest, with compartments containing all the correct tools, accessories and spares. McLean went through his well-practiced routine of preparing the unit for firing, emphasizing that all necessary safety steps had been performed well ahead of time, including hydrostatic testing of the fuel and pressure tanks and careful attention to valves and fittings on the restored flame gun.

After pouring in the requisite amount of kerosene and diesel fuel mixture (sorry, no super dangerous gelled gasoline today) and pumping compressed air into the pressure tank, he walked us through the steps necessary to install and arm a surplus ignition cylinder. This fascinating sequence is seen in the accompanying photos, just as it was done countless times by Marines and GIs in WW2.

McLean’s dedication to authenticity extends to both the flamethrower and the Leatherneck “utilities” he’s correctly uniformed in, a requirement for all “historical interpretive specialists” who are held to the strictest standards by the USMCHC.

“Fire in the Hole!”

A crowd of spectators had gathered behind the safety zone rope, many with cameras ready in eager anticipation of the spectacular demonstration that was promised. Introduced by a member of the Company, McLean walked deliberately forward to the firing line, burdened by the heavy apparatus.

At the conclusion of the short explanatory narrative, the GO signal was a loudly shouted “FIRE IN THE HOLE,” a familiar and multi-purpose exclamation that warns of serious things immediately to come.

Our camera position was closer than that of the other spectators so, when McLean pulled the trigger on the forward grip, we could clearly hear the distinctive pop of the first charge in the ignition cylinder lighting up. This was immediately followed by a sinister hiss and cascading sparks from its brightly burning magnesium filler.

Then, McLean the “WW2 Marine,” leaning forward to compensate for the strong rearward push that comes with launching each high pressure fuel stream, unleashed a searing burst of flame. This also made a distinctive sound, not unlike that of a fighter jet’s afterburner in the distance.

Each pull by McLean on the gun’s rear grip fuel valve sent angry streams of fire downrange, turning color in flight from white at the muzzle to yellow and orange. Ominous black smoke billowed skyward and the choking stench of scorched diesel fuel assailed the nostrils, all accompanied by intense heat and an other-worldly noise.

It took little in the way of imagination to appreciate the oft-repeated truth that – as horrible this weapon’s casualty producing effects undoubtedly are – invoking primal, uncontrollable fear is its greatest asset.

After exhausting the last drops of fuel and making sure the ignition cartridge had completely burned itself out, McLean moved closer to the crowd to provide a show-and-tell session. Wary children stared at the devilish device and energized adults peppered its owner with detailed questions both technical and tactical.

This, in essence, is the payoff inherent in one of the central elements of the USMCHC’s mission – to develop and provide outreach and traveling historical educational programming focused on telling the Marine Corps story. And the role of the flamethrower in action in the Pacific in WW2 is a spectacular chapter in this distinguished, ongoing story.

August 2000, Solomons, Maryland. Larry McLean conducting one of several live fire demonstrations with his meticulously correct WW2 vintage M2-2 device. McLean and others of the Marine Corps Historical Company provided an impressive living history display on the grounds of the Calvert Marine Museum for the 58th anniversary of the Marine Corps’ invasion of Japanese-held Guadalcanal. This and subsequent “island hopping” landings were launched by many of the Marines and Sailors who had intensively prepared on Chesapeake Bay beaches near the U.S. Naval Amphibious Training Base in Calvert County.

1. Larry McLean, dedicated flamethrower enthusiast and restorer, inspects the regulator and adjusts the shoulder straps on his fully restored and functionally exact WW2 vintage M2-2 for the Marine Corps Historical Company’s afternoon live fire demonstration. The two large tanks hold the fuel mixture and the smaller one is pumped up with ordinary compressed air to push the fuel out, down the hose and out the gun group. The unit has been fueled, pressurized and will be ready to shoot after installing a rare and costly original ignition cylinder. McLean’s dedication to authenticity extends to both the flamethrower and the Marine Corps “utilities” he’s uniformed in. (Robert Bruce)

2.: With the conical ignition shield removed, we get a close look at the spring case on the pistol-like ignition head assembly. This unwinds under spring tension in steps with each pull of the trigger, indexing each of five extended “matches” in the ignition cylinder for a striker pin to ignite the incendiary charge. Note the needle valve extending from the center of the fuel tube. This is controlled by a squeeze bar trigger in the rear part of the gun assembly, releasing a stream of thickened fuel and then securely shutting it off to prevent catastrophic “flash back” in the fuel tanks. (Robert Bruce)

3. Instantly setting it apart from propane torch-ignited flame guns employed in nearly all of today‘s public demonstrations, the “star” component of McLean’s M2-2 flamethrower is use of military surplus original ignition cylinders. These are damnably expensive and nearly impossible to find but McLean has managed to secure what he calls an adequate supply for special demonstrations. Seen here with the airtight storage can that has preserved it in firing condition since 1967 during the Vietnam War, the bottom of the black, high temperature plastic cylinder has five “matches.” Each is driven forward in turn by a striker to ignite the ultra-hot magnesium incendiary charge that reliably lights the fuel stream under even the worst environmental conditions. (Robert Bruce)

4. After placing the ignition cylinder on the ignition head, turning it to wind its internal clock spring to the first position and replacing the stamped steel ignition shield, the gun group is ready to fire. The conical shield protects against strong winds and torrential rain, concentrating the fiercely burning magnesium sparks that flawlessly ignite the fuel stream. (Robert Bruce)

Toxicology: How Flame Weapons Kill

“In studying the toxicology of flame attack in poorly ventilated enclosed spaces like those found in Japanese bunkers and similar fortifications, researchers determined that three important changes occurred within them at the moment of flame attack, quite aside from penetration of the flaming fuel itself: there was a sudden jump in temperature, lethal concentrations of carbon monoxide were built up in the bunker, and there was a dangerous lowering of oxygen content… Any one of these factors, or any combination of them, therefore, meant certain death, quite aside from the effects of direct contact with the flame.”

(Excerpted from THE CHEMICAL WARFARE SERVICE: FROM LABORATORY TO FIELD, United States Army in World War II series, The Technical Services, Office of the Chief of Military History, US Government Printing Office.)

(The author acknowledges with great appreciation the cooperation and assistance given by the USMCHC and by M2-2 flamethrower preservationist Larry McLean. Also for extensive and valuable information posted by noted flame weapon authority Charles S. Hobson at flamethrowerexpert.com There, one will find history, model identification, display units, working units for sale, restorations, movie industry links, and much more including the complete articles he has written on flamethrowers for various magazines including Small Arms Review’s November 2009 edition.)

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V18N5 (October 2014) |