By David Lake

No magazine will likely ever be the star addition to your gun collection. The magazine will never get an honorable mention in a war documentary. It’s just a small rectangular device we often take for granted as a necessary peripheral item that facilitates our shooting hobby. The detachable ammunition-feeding device should be more. It should be held in high regard—as something of great historical interest and significance. The development of the detachable magazine parallels the history and development of the small arm—as the modern repeating arm could not exist without its magazine.

History

In the interest of brevity, the internal box magazine common to bolt-action rifles, as well as the stripper clip, used to top off a fixed magazine and the aging single-stack magazine will only be discussed here in comparative reference. This is about the high capacity magazine: Man’s best attempts to provide the soldier and hobbyist with the most firepower he can hold in his two hands. To not wax political, there will be little mention here of any magazine that holds fewer than 11 rounds. As a general consideration, a high capacity magazine is one that is only limited in its size and capacity by the intent and functionality prescribed by that weapon’s designer, as any weapon must remain practical and convenient for the user of said weapon. Surely, the advent of the magazine as it is accepted today must be attributed to the military’s need for superior firepower. As warring forces sought to outdo one another, the infantry arm has always been at the forefront of the (literal) arms race. More power, more distance, higher fire rate and more ammo all equate to success and dominance over an opposing force. This endeavor continues with the military as well as modern law enforcement today. As it applies to the hobby shooter, we accept and uphold that it is our right as Americans to own and utilize our small arms for any and all lawful purposes. The practicality and utility of a high-capacity feeding device are not in question, nor can the importance and significance of the high cap mag be refuted.

The repeating arm became a viable weapon shortly after the invention of the self-contained cartridge in the late 1800s. Through the 1890s, firearm inventors began designing small arms around the detachable box magazine as we know it today—and as soon as it became established, it would quickly find broad success in pistol and submachine gun (SMG) designs of the day. Despite the obvious advantages of the detachable box, militaries around the world seemed to distrust or otherwise ignored the new technology as it applied to the full-powered infantry rifle. The stripper-fed internal box would remain the standard for the infantry rifle until the 1940s.

It has been well-demonstrated that a weapon’s magazine can make or break that particular weapon’s story of success on the battlefield. The famously miserable French Chauchat machine gun featured a magazine with large openings on the sides to provide the user with a visual indication of his remaining ammo supply. The short-sighted design also provided mud, dirt and vegetation an easy path into the gun’s mechanism. On the other hand, the British Sterling submachine gun has enjoyed a half century of distinguished service—renowned as one of the best small arms ever made. Some experts suggest it’s got much to do with the peerless design and craftsmanship of the magazine. The Sterling’s 34-round magazine is made of four welded strips of very thick high carbon steel. There’s a generous feed ramp built into the mag body where the cartridges exit. The follower consists of roller bearings that act as guides below the cartridges. And the follower is very tall—effectively what we might call “anti-tilt” today. Its inventor, George Patchett, saw the magazine less as a disposable sheet metal tube and more as a necessary and integral part of a complex mechanism—no less important than the stock, bolt or barrel.

From WWI though the 1950s we saw many variations and configurations of how the magazine interfaced with its host weapon. In the past, some would protrude vertically from the top of a gun while others extend out to the side. Today most magazines hang succinctly below the weapon. But the magazine’s orientation on the weapons of war was neither random nor arbitrary. These engineering decisions came from lessons learned in battle. WWI taught that when firing from cover, specifically from within a trench or behind a low barricade, a ventrally oriented 30+-round (long) magazine could interfere with the soldier’s ability to maintain safe cover and also confound the reloading of his weapon. In the vast mud puddle that was World-War-I France, it became evident that any opening on the belly of a weapon was a point of potential infiltration for debris. So the belief became widely adopted that a magazine needed to be located anywhere but the bottom of the action. Submachine guns like the Bergmann, Lanchester, Sten and Sterling had horizontally oriented magazines. The high-powered Johnson light machine gun (LMG) and the Fallshirmjagergewehr 42 would also feature horizontally arranged magazines protruding to the left of the action. In the case of the FG-42, it has been suggested that the magazine’s orientation would allow German paratroopers to more easily engage ground troops below while hanging from their parachute. Light machine guns like the BREN, Madsen, Japanese Type 96 and German MG15 had magazines that stood vertically from the surface of the receiver. The German MG15, as well as its near clone, the Japanese Type 98, were more commonly used with a double drum instead of the vertical box. The double drum, by placing the ammo directly to the sides of the gun, gave the user an unimpeded vision of the zone of fire. The Lewis gun and Russian Degtyaryov light machine guns were also fed from the top of the receiver but utilized flat drums with the ammo arranged around the drum like the pistons of a radial aircraft engine. This configuration provided better visibility than the vertically oriented magazine but introduced its own degree of complexity and a resultant potential for failure. These machine guns—with horizontal drums— were commonly mounted in early aircraft presumably due to the improved visibility and increased ammunition capacity afforded by this magazine type.

Belt-Fed

Where the high capacity box mag often fell short was its constant need to be replaced. Even the higher capacity drums—50, 75 or even 100 rounds—posed some logistical difficulties. As magazine capacity increased, so did the mechanism’s complexity and potential for failure. As battle tactics have changed over the past 100 years so has the role of the machine gun. A heavy machine gun may be asked to hold a position and perform area denial against advancing forces. This is the place and time for a belt-fed gun. The light machine gunner may be asked to advance, displace or relocate depending on the flow of the battle. The light machine gunner needs a more mobile and adaptable weapon. The ultimate result of the multi-role demand of the light machine gun was the Squad Automatic Weapon—a light machine gun that accepts belted ammo as well as detachable box or drum mags. Our M249, or generically the SAW, is that weapon. Other nations have resorted to hanging a hollow metal box on their belt-fed light machine gun. This belt box holds and protects a belt of linked ammo and allows for the LMG to be maneuvered and handled like a battle rifle. Belt boxes usually hold between 75 and 200 rounds of linked ammo. The RPD has been a very a successful LMG and notable example of this later configuration.

Feed Types

Essentially there are two ways to stack and store ammo in a magazine—single stack and staggered or nested. Single stack is just that. A single row of cartridges with mag body on either side, a follower below and feed lips above. The staggered magazine keeps two rows of ammo housed within the mag body—usually the cartridges will nest perfectly against one another. That is, each round is in contact with four neighboring rounds. A magazine that allows for proper nesting of ammo makes the best use of capacity given a certain size. This type of magazine generally features what is known as a dual presentation at the feed section. The ammunition remains in its own vertical column as it rises into location where the bolt may strip and feed in into the chamber. Cartridges are loaded alternately from the left, then right, then left side again. The magazines of the UZI and AR-15 clearly demonstrate this type of feeding.

Some mags provide a single presentation at the feed section. That is, the two columns of ammo are forced to merge into a single row before being presented into the bolt’s path for stripping and loading into the chamber. The weapon loads ammo from the same central location every time. These mags typically use a staggered but not a perfectly nested storage configuration. The internal width of these mags is slightly less than that of a properly nested dual presentation magazine. As such, they do not make as efficient use of size vs. capacity. The magazines of the Sten SMG and Glock pistol clearly demonstrate this type of feed configuration.

Very High Capacity Drums and Boxes

There have been some exceptional mutations to the basic box or stick magazine. The Finish Suomi KP/31 was a highly developed submachine gun of WWII. It could utilize any of several different magazine types—sticks, drums and something called a “Coffin mag.” The Coffin mag (aka “quad stack”) is essentially two conjoined double-stacked mags. Toward the top, each half tapers and feeds into a single row just before those two single-stacked rows merge into another double row. Then that double-stack tapers and merges again into a single stack up to a single presentation feed section. It’s complex, to be sure. It’s sensitive to the physical condition of the ammunition. It’s sensitive to dirt or sand. And sensitive to any minor damage or deformation to the magazine body. But the Suomi Coffin mag holds 50 rounds, while its length remains equal to the Suomi’s standard 36-round stick mag. This type of magazine has been refined and adapted to the AR-15 platform by Surefire, in a 60- and 100-round option. The AK-47 platform has teased at the existence of a “quad-stacked” mag for some time now, and recently we have seen the commercial availability of such an item.

The proper drum mag may be getting on in years. They have existed for over a century and have been or are currently available for most weapon platforms. There are three types to be encountered. Those with a single row of cartridges tracing the interior of the drum body. This type is common to modern weapons chambered in 12 gauge, 22 long rifle and 9mm Luger. Other drums store ammunition in a spiral—beginning with the single outer row then transitioning into an ever-decreasing circular path. The AK-47, Thompson and PPSH drums are of this type. These always include a cog fan-shaped rotor that carries small clusters of cartridges though the spiral path and keeps them aligned and oriented. The last configuration is merely a double-stack magazine that curves abruptly to the left or right into a circular pattern. Today’s common commercial offerings for the AR-15 and Mini-14 platforms are generally this sort. One exceptional variation to this design is the double drum. The double drum is not new. The German MG15 was fielded almost exclusively with this unique magazine. It presents as a pair of small drums—one to either side of the action. One great advantage of this design is its compact nature. It adds little to no height to the weapon when affixed. It doesn’t impede shooter’s line of sight over the weapon in the case of a top-fed gun, nor does it prevent the shooter from firing from a low prone position in the case of a bottom fed weapon. The double drum was first adapted to the M16 / AR-15 pattern in the late 1980s by the Beta Company. This device became known simply as the “Beta mag.” Unlike the early German incarnation, the Beta mag was designed to be serviceable and adaptable—the feed section could be interchanged to fit other weapon platforms or replaced as required to maintain reliable function. Each half of the mag is indeed a bent double-stack mag, and each merges into a single stack before being introduced to its neighboring single-stack row of ammo to form a new double stack of ammo in a dual presentation feed section. The mags feature a device called a “feed chain” (a common device in many drums mags) that presents as several cartridge analogs joined by chain links. This part of the invention provides constant pressure and feeding while the main follower remains inside the drum body.

Materials and Construction

The first detachable box magazines were made from sheet metal; some were two pieces that were formed and soldered, welded or brazed together. The Sterling SMG magazine was crafted from four strips of steel that were formed then spot-welded together. Later development saw the use of single metal sheets being formed then welded, brazed or soldered along a single seam. The most recent advancements in metal fabrication have provided seamless metal tubing that may be formed into a box magazine. Many early battle rifles featured what we consider today as detachable box magazines; however, these magazines were intended to be kept as part of the firearm and thus often loaded while in the weapon with a stripper clip. These magazines were heavy, robust and expertly crafted from thick steel. The Enfield, Gewehr 43 and FN 49 are examples of battle rifles that were issued with high quality detachable magazines, but each rifle was issued with just a few magazines. The user would replace the mag if and only if required to keep the weapon functioning. The soldiers wielding these rifles were trained and equipped to “top off” an empty box magazine via stripper while the bolt was locked rearward.

The infamous assault rifle of WWII Germany, the STG-44, was among the first high-power assault rifles built without a stripper clip guide. The user would carry a supply of full magazines—as each mag became exhausted it would be discarded and replaced with another full mag. As the magazine became a disposable device, its construction needed to become faster and cheaper. Metal fabrication techniques would have to adapt to fulfil this demand—the disposable magazine would have to be perfect—while retaining the reliability of the hand-crafted reusable magazines of decades past.

Through the 1950s, 60s and even 70s, the magazine was often culpable as a weak point in the battle-rifle equation. Mass-produced magazines were fragile; they were dimensionally inconsistent, and the sheet metal magazine would face compromise, sometimes made from ductile aluminum or made from steel just thicker than foil. Some of these compromises were enacted to satisfy cost restrictions. Some were to satisfy weight restrictions. We can see the struggle of the engineers when faced with government intervention—their attempts to make the best of the mag given certain limitations in cost or weight. One successful way to make the magazine body more rigid was to incorporate grooves and ribs in the magazine body. This technique is still employed by modern manufacturers of metal rifle magazines. Some early sheet metal mags featured bolsters and extra layers of thick plate or even steel castings or machined components mated to the thin sheet metal bodies. The feed lips were a common point of failure, as they are responsible for cartridge presentation and easily damaged by even mild impacts or abuse. The original AK magazine makes a relevant example. The thin sheet metal body would serve only as bulk storage of ammunition while the part of the mag that interfaced with the weapon—the feed lips and locking surfaces—were crafted from heavy castings or even machined from solid steel or aluminum.

The most recent positive change in the development and perfection of the magazine would inarguably be found in polymer science. Synthetic magazines were around as early as the 1960s but not as we know them today. Early magazine endeavors to craft the magazine body from lighter and more resilient materials produced what today we would call composite construction. Back to the AK platform for another relevant example; Russian designers were experimenting with phenolic resins and other synthetic bonding agents melded with organic fibers, or vice versa, synthetic fiber bound in a matrix of organic bonding agents. These early polymer mags were lighter than steel, tougher than aluminum and highly resistant to the failures associated with environmental exposure common to the field of battle. Although at its infancy, the synthetic magazine of the 1960s and 70s would cost more to produce than its comparable sheet metal version. As with all new technologies, time and science would solve this problem.

Today, without much need for a supportive example, it is safe to posit that polymer has been established as king of the hill. Most major arms manufacturers today have succumbed to crafting at least a few magazines from polymer. Even the mighty Heckler and Koch, arguably the best sheet metal crafter in the world, now makes polymer rifle and pistol magazines. With that assumption, many pistol magazines are still made from steel. And even Glock, famed for the plastic gun they brought into popular favor, still furnishes a steel magazine, which has been clad in a layer of polymer. Only by very recent advancements in exotic plastics such as flouropolymers have manufacturers been able to produce consistent and reliable pistol-caliber magazines that can compete with the longevity and performance of the best metal bodies.

Failures

Since WWI, the Japanese produced one exquisitely deficient machine gun—mostly faulted for how its ammunition was fed. It was called the Type 11 and had a hopper mechanism that fed 5-round strippers full of ammo into the gun—the same strippers used by the infantry to feed their bolt rifles. Seems like a sound idea, until one learns that the hopper only held six stripper clips (30 rounds—enough for almost 4 seconds of fire). Keeping the Type 11 full of ammo was a full-time job for one man while another man would aim and fire the gun.

The Italians managed to impress and fail simultaneously. One of the most beautiful WWII weapons is the Breda 30. Today it is regarded as a treasure of the old world and appreciated as a tragic work of art. When one considers its battlefield prowess, the Breda makes the list for not having any. The magazine was hinged to the gun—not detachable at all. The box would pivot forward to facilitate loading with a 20-round charger before the magazine would be rotated back into position. Every time the charger was inserted into the magazine, dirt and debris was also introduced. Particulate and foreign material would build up in the mag to the point of malfunction. The magazine featured an opening to provide a visual indication of remaining ammo supply and another way for dirt to get into the gun. This arcane beauty can barely be considered a machine gun at all. But the mechanism and magazine are unique enough to deserve an honorable mention.

Notable Variations and Exceptions

The basic pattern of the high capacity magazine has been rubber-stamped across the industry: sheet metal or polymer body; coil spring; and plastic anti-tilt follower. Just apply a few dimensional specifics to this basic recipe, and one can provide a magazine for almost every weapon on the planet. Some designs have deviated from this basic approach. Sometimes a bit of extra complexity can solve a real-world problem. The following are a few examples of some magazine designs that have stepped out of line a bit in order to enhance the form and function of the weapons they feed.

Helical Magazines

These are rare but not totally unique to any one weapon platform. A helical magazine arranges and stores ammunition in a spiral around a cylindrical magazine body. Its advantages are easy to qualify; it makes more efficient use of space than a box mag, and it need not protrude from the weapon like a box mag. Instead, it can lay alongside or under the gun. Ammunition capacity is higher in a helical magazine compared to a similarly sized box mag; ammo can occupy the entire length of the mag as there is no spring and follower under the column of ammo. Instead, a torsion spring resides in the space inside the helix of cartridges. The most notable weapon platforms using this type of high capacity magazine are the US-made Calico and the cold-war era Soviet Bison SMG. Several large aircraft cannon in military service utilize a similar ammunition handling mechanism.

FN P90

The magazine of this PDW (personal defensive weapon) lays atop the gun lengthwise. The 50-round box extends from within an inch of the muzzle back to the shooter’s cheek weld where ammunition is fed into this semi-bullpup “gun” (the P90 is neither rifle, nor pistol, nor carbine). The odd factor here is that the ammunition settles horizontally into the magazine and perpendicular to the barrel. As the ammo descends from the mag into the bolt’s path for loading, each cartridge must rotate 90 degrees clockwise as it drops through the feed “turret” of the magazine. Ahead of the follower there are two free-floating rods—the same diameter as the 5.7×29 cartridge but just too large to exit the feed turret. These rods can perform the trick of rounding the corner and forcing all cartridges from the magazine; a trick the follower alone cannot perform. And the ammunition manages to make this trip at such a rate that this gun can maintain a full-auto rate of 900 rounds per minute. This mechanism is constructed entirely of low-friction polymer materials.

Boberg Arms XR9 (Currently Bond Arms Bullpup)

This small firm created a compact semi-auto pistol with a very special magazine and feeding process. The unique engineering allows the XR9 (Bullpup) to count itself as the smallest semi-auto pistol in the world per given barrel length. The key piece to this puzzle is how the magazine dispenses ammunition—to the rear. That is, ammunition is extracted from the magazine as the slide travels rearward. As the slide is under recoil, the mag presents a cartridge into a position where a pair of arms can grasp the case rim and pull it from the mag. As the slide starts forward, the round is elevated above and over the magazine and into alignment with the barrel. The advantages of this system are clear: the barrel can be longer than other pistols of similar overall size (chamber is above the mag, not ahead of it). Also, the extraction cycle is performed by direct energy generated by the fired round rather than stored energy from a compressed recoil spring. However labored the operating cycle endured by this little pistol, its magazine will surely remain among the most unique. And to make it sound even more unlikely, the magazine has no follower.

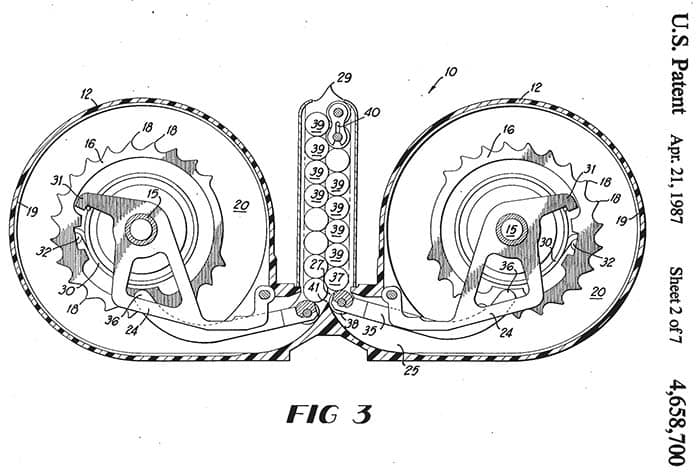

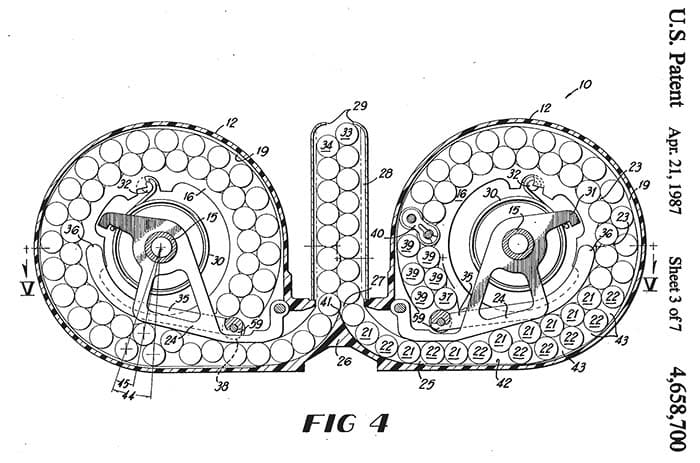

The “Beta” 100-Round Double Drum

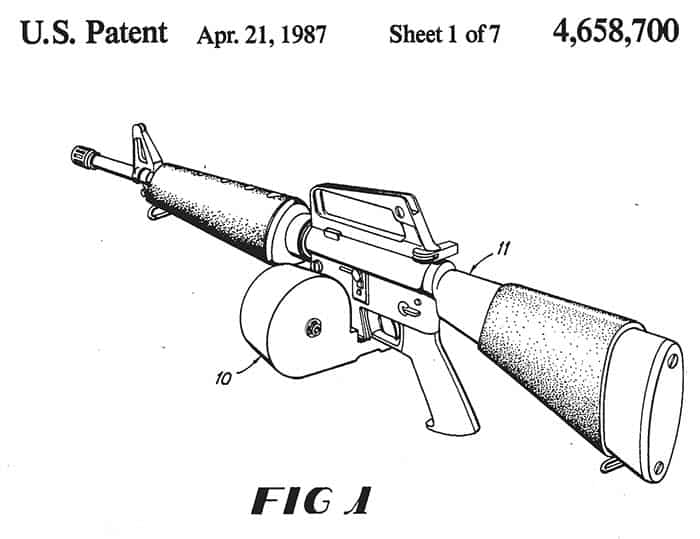

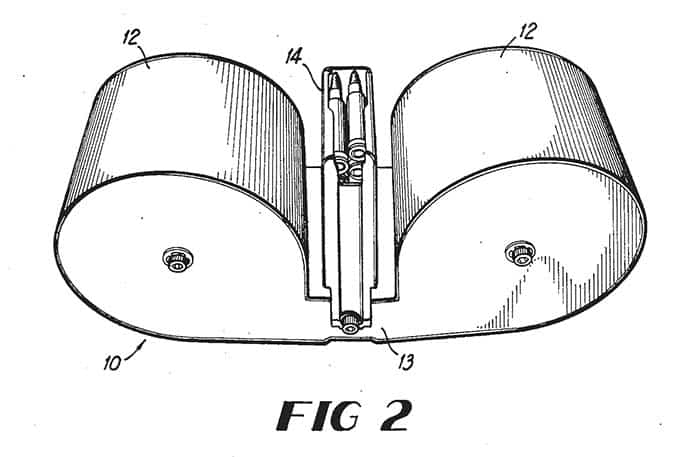

Shown here in the original patent description is the Beta 100-round double drum designed by L. James Sullivan of AR-15 and Ultimax 100 fame; how it places the ammunition supply in a tight efficient location at the sides of the rifle.

This magazine can be fitted to a rifle without interfering with any handling or operation required of the user. The only disadvantage to a 100-round magazine of this sort would be its weight when fully loaded.

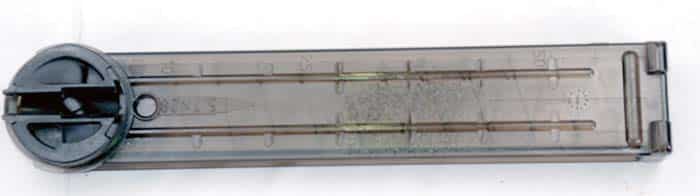

The ammo supply is distributed equally to each drum and fed to the rifle via the central feed tower.

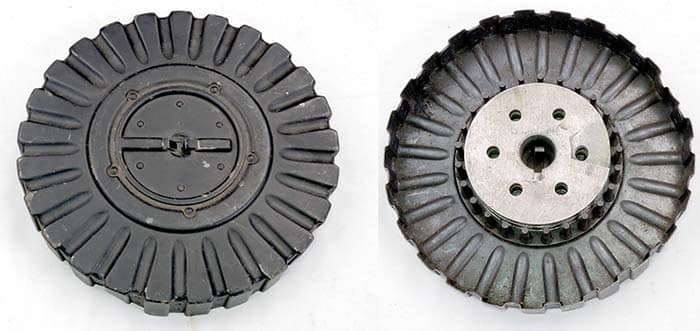

The Beta mag full of ammunition. Note that at the bottom section the staggered column of ammunition is merged into a single row, thereafter that single column is rejoined with its neighboring column in the feed tower to form a double-stacked, dual-presentation ammunition supply.

The Beta mag when empty. Note the feed chains in the feed tower. This collection of linked dummy cartridges allows the followers, which are housed only within the drum bodies, to feed ammunition completely through the feed tower. There are two separate feed chains—one connected to each follower, in each drum.

This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V22N9 (November 2018)