By Terry Edwards –

“Live dangerously; as carefully as possible.” –Colonel “Mad Mike” Hoare

Colonel Michael “Mad Mike” Hoare died peacefully in his sleep while I worked on this article. His eldest son, Chris, emailed me the news from Durban, South Africa.

Outside, a wind levelled the snow, evoking a winter long ago when escape called from the cork board near my grade six desk. Under “Current Events” a newspaper photo featured mercenaries and machine guns in the “Congo Crisis.” Led by a charismatic Colonel Hoare, they battled insane odds to rescue thousands of innocents from the evil “Simbas.” For myself, and countless others, the coverage was, as Colonel Hoare might understate, formative.

The 1960s Congo Crisis was largely a struggle between the “Capitalist West” and the Communist East. At stake were strategic uranium and cobalt mines. The vast majority of victims in the fight were Black Congolese, but the desperate situation of foreigners stranded in bloody mayhem captured the attention of the western press. That’s the political and human side.

On the cultural side, something unexpected happened. If it wasn’t born in the Congo, the popular paramilitary culture was legitimized there, and Colonel Hoare was its polished, middle-aged poster child. Hoare projected morality and manners, made military adventure heroic and stoked an appetite for all things military. Richard Burton portrayed Colonel Hoare in the British blockbuster feature, “The Wild Geese.”

In 1960s Congo, Hoare’s men labelled their unit newsletter “The Volunteer.” In a fitting incarnation, Soldier of Fortune (SOF) magazine was introduced in the U.S. in 1975. SOF has triumphed over lawsuits and hate campaigns for 45 years. Machine Gun News, another pioneer magazine born in the time, grew into the distinguished Small Arms Review.

In May 2019, Colonel Hoare turned 100. Chris Hoare, an accomplished writer and author many readers are familiar with, commemorated this with a superlative biography of his father, “Mad Mike” Hoare: The Legend.

I was fortunate to meet Colonel Hoare in the 1970s. Regardless of the nickname, there was nothing “Mad” about “Mad Mike.” A compact, good-humored and engaging gentleman, Colonel Hoare was a man at ease with himself and easy to be with. I flatter myself that we hit it off… I would never presume to call him Mike.

He smiled when I handed him my scoped FN FAL rifle. It settled into his hands like a part of him. He knew it well. Touted as “the free world’s right arm,” the FAL (Fusil Automatique Léger/Light Automatic Rifle) was carried by much of NATO and by Hoare’s men in all his Congo adventures. It is a symbol of the Cold War and the Congo. There was a lot of competition in the Congo. Between the guns of the combatants and the peacekeepers just about every well-known 20th century military small arm saw use there.

No specific gun determined or changed the course of the conflict, but some weapons rose to engineered art. Conceived and made in the red brick Fabrique Nationale d’Armes de Guerre factory in the Liège suburb of Herstal, Belgium, the FAL was a machined expression of national and personal pride … a design and master work in steel and wood. At the factory, FAL is often pronounced as a single word to rhyme with pal. The heavy barrel variant is called a “FAL-O.”

Long before Fabrique Nationale came into being, dozens of Liège gun factories made muzzle-loading trade guns. Powerful tribes in the Congo River Basin had slaves and gold to trade. In the 1890s, Katanga Chief Msiri commanded 10,000 warriors, most carrying cartridge rifles.

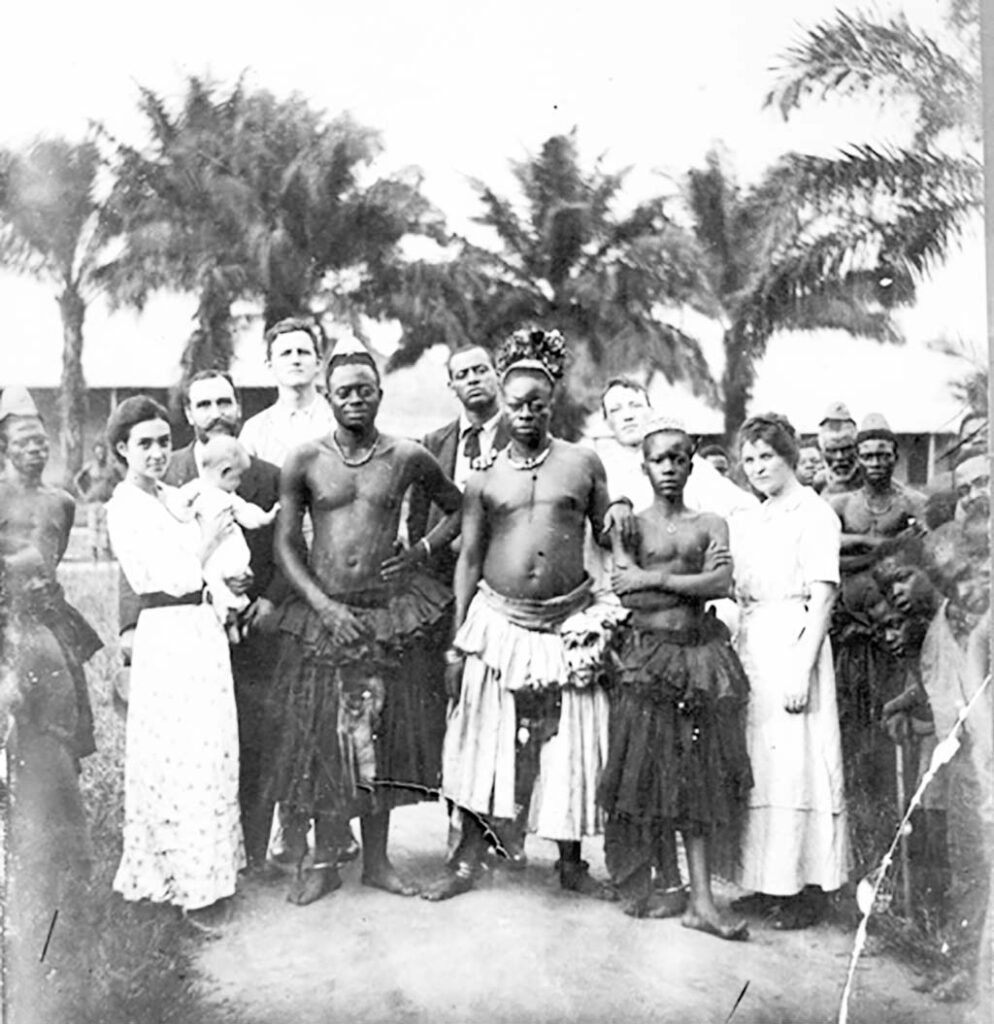

Belgian King Leopold II staked out much of central Africa as his personal property in 1885 with trading posts, mines and plantations. The Congo Free State, as he named his private African country, was about one quarter the size of the United States. Leopold borrowed money from the Belgian government to finance it all and created the “Force Publique” to enforce his control.

White, mostly Belgian, officers commanded ranks of Black Africans. Many of Leopold’s enforcers carried single-shot, 11mm Albini-Braendlin and Comblain No. 2 rifles. The Albini-Braendlin breech was similar to the trapdoor Springfield, while the Comblain No. 2 had a vertically sliding breech block much like the American Sharps. Both used black powder to fire slow, heavy bullets.

In the forefront of the smokeless powder era, Belgium adopted the Model 1889 rifle, a modern Mauser bolt-action. Belgium wanted the German–Belgian hybrid made in Belgium. To fill the huge national contract, several gun makers in Liège joined with the German firm Ludwig Loewe to become the renowned firm Fabrique Nationale.

The Model 1889 had a built-in, five-shot, single-stack magazine. Its new small-caliber, high-speed bullet launched from a rimless, bottle-neck cartridge. The bolt-action design was similar to the 71/84 Mauser black-powder rifle, but the Model 1889 could be loaded by a single round or with a five-round stripper-clip. The Mannlicher competition also used “clips,” but those were inserted as loaded units into the gun; the en-bloc system was later used in the M1 Garand. The rifle was also adopted as the Argentine 1891 and the Turkish 1890. The blued-steel barrel jacket is often mistaken for the barrel itself. Carbine and short rifle versions were produced.

The Model 1889 rifle was made for Belgium and the Free State of the Congo. During WWI, when the FN plant was occupied by German invaders, Belgium had the Model 1889 made at Hopkins & Allen in the U.S. and W.W. Greener in Britain. Between the World Wars, many Belgian Model 1889s were rebuilt into shorter, lighter 1889/36 rifles. Shed of the Model 1889s barrel jackets, they served alongside belt-fed Maxims and magazine-fed Madsen Light Machine Guns (LMGs).

Belgium was slow to issue the more effective modern guns to the often surly Force Publique. Leopold’s was a ruthless reign. Rubber was the crop, and if a harvest worker was slow, the penalty of losing a hand inspired those remaining. It was all quite profitable, and Congo towns grew into Belgian-like cities. The veneer of Christian missions and tidy schools crumbled quickly after the British press first exposed a catalog of atrocities. World opinion shamed Leopold into giving the Congo Free State to Belgium. It became the Belgian Congo in 1908.

In the wave of 1950s anti-colonialism, the Black Congolese demanded independence from Belgium. An early leader was Patrice Lumumba, born in 1925. His unpromising, and much longer, full name meant, “Heir of the Cursed.” Smart, educated and highly political, Lumumba was a postal worker until 1956 when he was jailed for embezzling while training in Belgium. He returned to the Congo expounding a vision of racial harmony, justice and equality. He was branded an anti-Catholic and anti-white Marxist and jailed for sedition.

During 1960, at least 17 colonies in Africa, mostly French, were freed in colonialism’s long-running train wreck. In 1959, bloody riots forced Belgium to announce free elections. Lumumba was released from jail and elected prime minister. His ally, Joseph Kasa-Vubu, was elected president. The Congo had two Black doctors, less than a dozen Black college graduates and two new Black Army Lieutenants.

The Independence Ceremonies

On June 30, 1960, the Independence ceremonies of the Republic of the Congo unfolded in Leopoldville. The joyful parade route was packed. Belgian King Baudouin took the salute of the Force Publique.

Select troops and police presented arms with the FN SAFN (FN-49). The SAFN is a 10-shot, long-wood semiautomatic rifle with a short-stroke tappet piston. It was internationally popular in several calibers, but the greatest part of SAFN production was in 30-06 caliber for Belgium and the Force Publique. Some Belgian-issued guns, called the ABL, had selective fire.

The pre-WWII SAFN design was a late bloomer and already obsolete as the guns were made. The basic operating design was soon reworked with a two-piece, straight line stock, pistol grip and high-capacity magazine to become the FAL.

During the parade, as the king’s open limo glided down Leopoldville Avenue, a dancing celebrant jogged alongside and grabbed the king’s sword. Luckily for his unamused majesty, the man, soon to be a local celebrity, only waved it harmlessly while continuing to dance in the parade.

From the podium, the ruffled king reminded the grumbling rabble of the blessings King Leopold II had showered upon them. Lumumba, who hadn’t been scheduled to speak, rose in outrage to decry Leopold’s cruelties and hail the bloody victory of rebellion. Reluctantly, the fuming king stayed for dinner before heading for the airport.

The celebrations were still going on when the former Force Publique, now the Armee Nationale Congolese (ANC,) mutinied, beating up and killing many of their white officers and civilians. Transition plans, naive and shaky to begin with, collapsed in lawlessness. Carloads of anxious whites formed a convoy south toward Rhodesia while thousands more overloaded the airports and ferries out.

Belgian troops flew back to the chaos to manage the evacuation. News photos showed Belgian paratroops with folding stock FALs, MAG 58 belt-fed machine guns (M240 in American) and select-fire 9mm Vigneron M2 submachine guns (SMGs). Colonel Georges Vigneron’s well-liked gun combined proven features of the M3 Grease Gun, the Sten, the MP 40 and even the Tommy gun.

Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu denounced the evacuation effort as an “imperialist invasion,” and demanded UN intervention.

As the rest of the Congo sank into violence and crime, the mining areas in the Katanga and nearby Kasaï province continued business as usual. Katanga was often derided as a glorified mining camp, but business was good, and no one of any color wanted to rock their happy boat. Katanga’s honestly elected Black leader, Moïse Kapenda Tshombe, was genuinely popular, and like his voters, a company man. The company was Union Minière du Haut Katangar (UMHK), a marriage between Belgian and British companies. Katanga ran on Union Minière wages and, with nearby Kasaï province, produced 60% of the world’s uranium, much of its cobalt and a buffet of rare minerals and gems.

Eleven days after independence, Katanga and Kasaï declared independence from the Republic of the Congo. Tshombe invited Belgian administrators, civilian workers, ex-officers and NCOs to stay in Katanga. Another 200 Belgian soldiers “transferred” to the Katanga Gendarmerie (police and armed forces). Tshombe closed the border.

Lumumba’s End, the Conflict’s Beginning

Lumumba visited America to get military support in retaking Katanga. The Congo needed the mines to survive; he pleaded to deaf ears. The U.S. already believed Lumumba was anti-American and a Communist. When he arrived in New York, his much-publicized demand for a blonde, white escort didn’t help.

Lumumba returned home and announced if Belgian forces were still there in two days, he would invite the Soviet Union to throw them out. The alarmed U.N. immediately landed Irish and Swedish peacekeeping troops. Period photos often show the Swedes with their M45 Carl Gustav submachine guns. The 9mm gun owes much of its excellent reputation to its toed-in, double-stack, double-feed magazine. In support, Sweden had license-built versions of the Browning 1919. The Irish carried FALs, Bren and Sten guns and Vickers water-cooled guns.

Lumumba welcomed the arrivals with anticipation. He expected the peacekeepers to restore Katanga to the Congo. But, Belgium, the United States and Britain, despite UN policy, supported the breakaway state. Suppression of Katanga was not a priority.

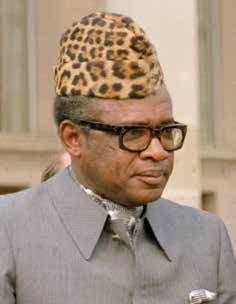

A few weeks after independence, the increasingly pro-Soviet Lumumba and Kasa-Vuba fell out. The Army Chief of Staff, Joseph-Désiré Mobutu stepped into the fray, and he and Kasa-Vuba handed Lumumba over to Tshombe. Tshombe was surprised to have Lumumba in his hands and wanted mostly to unload him back on Mobutu. Instead Lumumba was killed. Various versions of his execution accuse Belgians, CIA operatives and Lumumba’s drunken guards. He became a Communist martyr and the Soviet Union named the Patrice Lumumba University in Moscow for him. The name was changed to Peoples’ Friendship University in 1992.

With the agreement of the U.S. and the U.K., Tshombe soon had two British ex-officers, Alistair Wick and Richard Brown, hiring white “volunteer” soldiers in South Africa and Rhodesia. Military experience was not essential. Today, the pay would be about $1,000 USD a week.

France, too, dispatched “volunteers” to Tshombe’s aid. Many were French Foreign Legionnaires. The officers were all French Army. The legion ranks included WWII Axis veterans, many also now veterans of the Algerian War and First Indochina War (French Indochina). They arrived with bolt-action MAS-36/52 and semiauto MAS-49 rifles, AAT-52 recoil-driven LMGs, MAT-49 SMGs and their Model 1935 pistols.

Katanga was largely surrounded by enemies. Tshombe’s historic tribal rivals, the Baluba, threatened from the north, and the ANC and the United Nations from the west. Kasaï province, isolated to the west of Katanga, was cut off and overrun by the ANC. Over 4 weeks, thousands died badly for being born into the same tribe as Tshombe. The United Nations troops did nothing to stop the slaughter.

“Volunteer” Hoare found himself at a Shinkolobwe Army base with the rank of captain and a command within “4 Commando.”

More on “Mad Mike”

Hoare was born on St. Patrick’s Day while his Irish parents lived in India. This made him British-born, and his English schooling instilled the ideals of duty, loyalty, honour and chivalry. He loved soldiering and wanted to attend Sandhurst, the British counterpart of West Point. It was more than he could afford, so Hoare joined the “Territorial Force,” as the British once called their part-time reserves, and settled reluctantly into accounting. When WWII started, his Territorial membership enabled Hoare to join the regular Army instantly. He aced the small arms school, was fast-tracked to officer training and was commissioned a second lieutenant. In the Far East, he fought under the aristocratic Brigadier Bernard Fergusson, who became his military role model. At the War’s end, Hoare was a major. He returned to Britain, having married Elizabeth Stott in India in 1945, and retired from national service. Chris Hoare was the first of their two boys, and they had a girl. In 1948, they moved to Durban, South Africa. Hoare was a professional accountant who preferred dealing in used cars and scrap. He motorcycled the length of Africa, sailed and guided several safaris and expeditions. On one adventure he became friends with a CIA agent. In 1961, Hoare, now divorced, married Phyllis Sims. They had two boys.

In Katanga, Hoare maintained his standards of appearance and demanded his men do so as well. For former Rhodesian and South African soldiers, a daily shave and British Army traditions were already the norm.

With much foot-dragging, U.N. forces and the equally unmotivated ANC made some probes against Katanga. Those operations failed, but provocatively, an Irish U.N. force established itself in control of Jadotville.

In September 1961, Tshombe surrounded Jadotville with his Katangese Gendarmes and Belgian and French mercenaries. Over several days of fighting, about 300 Black Katangese Gendarmes, and a very few white mercenaries, fell in failed attacks. The Irish surrendered when their supplies and ammunition ran out. They had not lost a man. Tshombe had kicked the U.N. out and avoided a “white bloodbath” that would have soured his Western allies. The movie “Jadotville” tells their story.

Dag Hammarskjöld, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, died during a “shuttle diplomacy” attempt to bring peace. He was shot down by the Katangese Air Force, or his pilots ran into an uncharted hill in Rhodesia. The crash is still a fury of conflicting, concealed, lost and manufactured evidence.

After Mobutu threw out the infuriated Communists, America and Western Europe were comfortable with reintegrating Katanga with the Congo. At the end of 1962, Katanga rejoined the Congo and Tshombe left Katanga to exile in Madrid. He took the checkbook with him, and stranded foreign mercenaries were happy to have the UN fly them home.

Lumumba’s ghost and his thousands of former supporters did not rest in peace. Pierre Mulele took over the surging rebel movement, and his chanted name became the rebel battle cry. The rebels called themselves “Simbas,” Swahili for “Lions.” Many had never held a firearm. Bows, spears, muzzle loaders and hand-made guns surrounded prized Mausers and SAFNs.

Soviet and Chinese aid upgraded the Simba arsenal with bolt-action M1891/30 and 1944 Moisin–Nagants, semiauto SVT rifles, PPSh 41 and PPS 43 SMGs, SKS carbines, AK-47s and DP-27 LMGs and RPD LMGs.

The Congo includes most of the jungle in Africa. The chrome bores of the handy SKSs and AK-47s were a God-send in the jungle humidity and unskilled hands. The Soviet 7.62X39mm intermediate cartridge was often preferred to the loud and heavy full-power rounds.

This was important to the “Jeunesse” as the youngest Simbas were called. These child soldiers set out to exterminate all literate Congolese. With help from magic, the “Mulele” battle chant was promised to turn enemy bullets to water. Part of the magic was “dagga,” a drink of alcohol, marijuana and pureed enemy genitalia.

The rebellion spread, and by mid-1964, the Simbas held much of the Congo. Mobutu was in sole charge of the government. There was no peace to keep and the U.N., having lost 200 men in mostly grisly fashion, pulled out. The Simba tide engulfed Stanleyville, and thousands of foreigners and Congolese were taken hostage by the rebels.

Hoare Returns

The day the U.N. departed, Mobutu invited Tshombe home to command the fight against the Simbas. Tshombe immediately rehired Mike Hoare and his volunteers from Katanga days.

Hoare landed to find the once magnificent Belgian base at Kamina derelict and stripped for scrap. There were no uniforms, no weapons, no money, and no beer. His new recruits included an unhealthy percentage of alcoholics, drug addicts, deviants, and criminals.

Scenes throughout the Congo repeated the panic after Independence. Again, American-Belgian rescue efforts were labelled an imperialist invasion, and the Union Nations assured the world the Simba atrocity stories were nonsense. Tshombe was reviled as an imperialist lackey throughout Black Africa.

Belgium supplied small arms for 1,000 mercenaries and 200 more advisors. The United States airlifted in trucks, jeeps, radios and supplies. Critical to the upcoming campaign was the compact and powerful air-force piloted by expert Cuban exiles.

The volunteer ranks thinned as the unsuited were weeded out. Major Hoare practiced military leadership: Lead from the front; be seen to share the hardships, yet keep a dignified distance; always have a back-up plan; and always appear calm. Morale rose with uniforms, pep talks and military decorum. Always a romantic, Hoare deemed his force “The Wild Geese” in tribute to the Irish mercenaries of earlier centuries. Hoare’s adventurist teenage son Chris flew in to join them, train with the FAL and serve as his father’s driver.

Hoare’s men replaced an initial issue of Spanish CETME rifles with new selective-fire FALs. Most of the men were comfortable with the FAL they had trained with in their home armies. While the recoil-operated CETME was reliable, it was less familiar, and the adjustable gas system of the FAL gives a degree of operator influence. The force of the gas striking the piston is controlled by regulating the size of a gas venting hole in the cylinder. If the gun should get sluggish; the rifleman can turn up the gas.

It wasn’t a matter of choice anyway. The Congo was a Belgian show. With the FALs, came M2 Browning .50s, MAG 58s and FN copies of the .30 BMG and Israeli Uzi.

Colonel Hoare has been pictured in the Congo wearing an FN Browning P-35 Hi-Power. Hoare also carried a 1911 .45. We know this from his words, and after a mercenary raped and publicly executed a captured female Simba, Hoare court martialed him and shot off the man’s big toes with his .45.

The Congo Crisis was becoming world news, and most of it was bad. Simbas held Albertville and hundreds of hostages, white and Black, faced torture and death. An unpredictable 12-year-old Simba “Sergeant Major” was a key figure in the bloodthirsty command.

is a sturdy and low trouble submachine gun. ROCK ISLAND AUCTION

Despite Albertville’s poor defense, the ANC’s advance was slow and failing. Speed was life for the hostages, but the road to Albertville would be dangerous and give away any chance of surprise. Albertville, like Kamina, is on the shore of Lake Tanganyika. Sixteen small outboards were available. Hoare was an experienced sailor, but a vocal dissident predicted they would all drown in the heavy waves. Hoare contradicted this with a sharp clout of his pistol and took two dozen volunteers north up the lake to attack Albertville in coordination with the ANC ground forces and CIA air cover.

After rough water, engine break-downs and a lethal and aborted landing under the enemies’ sights, they reached shore. They marched north by road. The morning sun lit fields and tribal villages. Women in colorful robes tended cooking fires. From the distant bush, a backdrop of haunting calls and throbbing drums announced the mercenaries’ approach. A Simba mob, wild-eyed on dagga and chanting, suddenly appeared and charged from ahead. All were teenagers. A few had bolt-action Mausers while most carried machetes, spears, bows and arrows and worn trade guns. Hoare’s men opened fire with 22 FALs and killed 28 Simbas.

The rebel defense of Albertville dissolved before the mercenaries, the reinvigorated ANC and the thundering aircraft overhead. Sadly, the rescuers were too late for many. Dozens of missionaries had been killed with unprintable cruelty. On seeing their tortured bodies, Hoare said that all their efforts had made “not an inch of progress.” Prayers were no doubt said at the next mandatory Church Parade.

Attack at Stanleyville

Leaving the horrors of Albertville, “5 Commando’s” Ferret armored cars spearheaded the march on Stanleyville where the stakes were even higher. Under the overall command of Belgian Colonel Frederic Vandewalle, 5 Commando, Cuban exiles, Belgians and the ANC planned to attack Stanleyville at the same moment as American planes dropped Belgian paratroopers.

The plight of the hostages and the hair-raising charge to Stanleyville overshadowed all other news. Everyone understood the terrorized white captives in Stanleyville had only been spared as human shields. Black Congolese had no such value, and public trials and executions went on for days in the town square. The Black elected mayor died watching the crowd eat his liver. The international media descended, and journalists in bush jackets struggled to write in the backs of trucks and jostled for radio time. The coverage was relentless.

Ambushes slowed the column. The standard counter-ambush drill was a barrage of rifle-launched grenades and automatic firepower. Belt-fed guns struggled in jungle foliage, but the column’s vehicle-mounted guns, mostly Brownings, smoothly produced overwhelming suppressive firepower. The first two ambushes were answered without loss of momentum. In the third ambush, a Cuban was hit in the stomach. After a pause the column rolled on.

The Simbas, often brave and fearless, were usually bad shots and tactically unaware. In the next village, however, wiser Simbas let the armored cars pass and raked the trucks following. Hoare’s men leapt out into the roadside grass, and several ended up fighting Simba warriors literally hand-to-hand.

Breathless reporting elevated Hoare and the mercenaries to celebrity status. The press shared the heroic aura when CBS reporter George Clay, was shot through the head. Five Commando burned down the village in retaliation. Hoare described the night push toward Stanleyville as the most frightening night of his life. Darkness and sanity stopped the advance. Hoare and his men slept uncomfortably in the rain.

At dawn, 5 Commando moved on. The air support arrived, and the radial engines of the T-28s and B-26s shook the ground as the planes punished the Simbas with rockets and .50-caliber machine guns.

At 6 a.m. on November 24, 1964, 5 Commando was still driving toward Stanleyville when the Belgian paratroopers landed with armored jeeps and Land Rovers. They advanced on the town square.

The white hostages now had no value, and Simbas herded 300 into the street with spears and rifles. The gunfire of the charging paratroopers was barely a block away when a witch doctor frantically ordered the wavering Simba guards to kill the prisoners. They started shooting and spearing the women and children first. The paratroopers arrived 4 minutes later. Dozens of hostages were already wounded and more than two dozen killed.

The Belgian paras, Belgian mercenaries, the ANC and 5 Commando cleared the city, rescuing dozens and ultimately thousands of people. More priests and missionaries were found tortured and killed. Black teachers and intellectuals typically had their tongues cut out before torture and death. The ANC took merciless revenge on captured Simbas.

Dozens of rescue missions scoured the bush for stranded, mostly missionary and mostly white families. Clothes and footprints in the mud of a river bank revealed British adults and children had been forced to strip, before being killed and thrown into the river. The outraged patrol tracked and killed the surprised Simbas and rescued 14 women. Another rescue patrol found the frantic parents of a 4-year-old girl who had run in terror into the jungle. Grimly, the patrol went out to search. In one of the Congo’s few happy endings, they found her alive.

Such heroic stories uplifted the world. Overnight, mercenaries were adulated by much of the media. The delighted Greatest Generation applauded one of its own for showing the world how-to again. It was never better. The western world sighed in relief, and the paparazzi moved on, but the Congo Crisis wasn’t over with the retaking of Stanleyville. Every day, Algeria, Ghana and Burundi pushed 30 tons of Russian and Chinese guns and munitions to the Simbas through southern Sudan and Uganda, and the killings went on.

Major Hoare was tired, but Mobutu promoted him to Lt. Colonel and convinced him to stay on. Hoare convoyed 5 Commando and the ANC to the northeast borders by road. When the ANC’s loudspeakers blared, “Scotland the Brave,” masses of people rose cheering. They were well received, and the dispirited Simbas deserted their positions leaving piles of arms and ammunition. Five Commando wrecked all the vital bridges and closed the northern border.

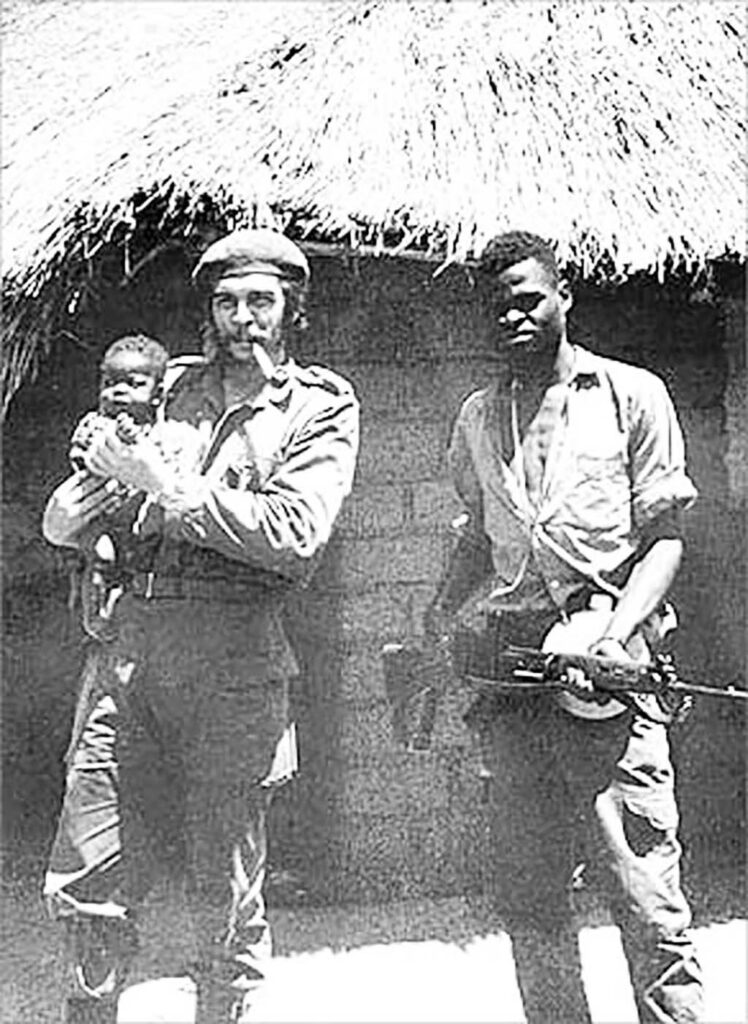

Hoare and his men returned to Albertville to stop more Communist supplies being smuggled across Lake Tanganyika. The enemy was drawn from a fierce tribe of warriors. Cuban advisors, led by Ernesto “Che” Guevara, trained them in weapons and tactics, and 5 Commando faced an improved enemy.

The threat didn’t last. A captured Cuban war journalist fumed in frustration with the rebels. When Guevara left after a few months, the witch doctors and the suicidal charges returned. Five Commando completed their last 1963 mission by retaking the towns of Baraka and Fizi. The unit was disbanded in 1967.

Hoare and his men returned to their homes. Through it all, Hoare met, knew and served many of the Congo’s leaders and generals. He spoke highly of several. He was not a racist. At one point, he had faith enough in the Congo to move his family there. Hoare even hoped his Commandos could remain and become a force for peace and justice in all of Africa. He admitted his impossible dream faded, but the world’s fascination never did; movies, TV shows, books and articles often portray the noble anti-hero as a mercenary on the right side. A whiff of Camelot still hangs in the air. While some cynics ask if the glorification is justified; few deny it.

Chris Hoare summed up Tshombe’s reward: “Tshombe, his job done, fell from grace; soon, he was kidnapped, and he died in prison in Algeria in 1969.” Among the many lives saved by 5 Commando and Hoare personally were several Canadians living today. Canada denied Hoare’s later bid to immigrate.

Mobutu renamed the Congo “Zaire” and ruled from 1965 until he was deposed in 1997. He left with an estimated $4 billion (with a “B”) U.S. dollars in offshore banks and died shortly afterwards. Zaire became the Democratic Republic of the Congo again. Peace, freedom and justice remain elusive.

Colonel Hoare was famous. In the British 1978 hit movie, “The Wild Geese,” Hoare was portrayed by Richard Burton supported by Roger Moore, Hardy Kruger and Richard Harris. Hoare was an advisor and appeared to have retired gracefully … but he hadn’t. On November 25, 1981, Hoare led several ex-5 Commando members and more than 40 men, recently of the South African and Rhodesian forces, onto a commercial aircraft. The flight took them to the Seychelles islands in the Indian Ocean east of Africa. They were there to overthrow the leftist regime of France-Albert René and reinstate President James Mancham. Their suitcases were packed with children’s toys and concealed assault rifles. When a Kalashnikov was discovered at airport customs, a Seychelles security officer and one of Hoare’s men were killed in the following fire-fight. The invaders negotiated a ceasefire and hijacked a 707 to take them back to South Africa. All of them served time. Hoare served almost 3 years of a 20-year prison sentence before being pardoned.

Hoare emerged and lived with his wife Phyllis in France for 20 years. He devoted himself to writing several more books and deeply explored the Cathars’ and their region. His books are available from madmikehoare.com and from audible.com with Colonel Hoare, himself, reading.

Hoare returned to South Africa in 2009. He enjoyed a Ballantine’s whiskey and water, or two, in the evening, curry (“the fiercer, the better”) and the Brit-com, “Dad’s Army.” Born in India, British to the marrow, he died in South Africa in 2020 after 100 extraordinary years.

The author gratefully thanks the late Colonel Mad Mike Hoare and his son Chris Hoare, James Samalea, Jay Bauser, G.N. Dentay, James and Melody Curtis Carol Mintoff, Gary Flanagan, Al J. Venter (all bookstores), David Logan, Lt. Colonel R.K. Brown, John W. Burns, Movie Armaments Group, Rachel Hoefing, Lisa Weder, Adam Bucci, the late Connie Mungall and the late R. Blake Stevens.

Chris Hoare’s “Mad Mike” Hoare: The Legend book is available in soft cover and in a numbered leather-bound edition signed by Mike Hoare, from www.madmikehoare.com.

Terry Edwards has published numerous articles with Soldier of Fortune, Small Arms Review and Small Arms Defense Journal. His books are available on Kindle, and his video “The Rifleman Who Went to War” is free on YouTube.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V25N1 (January 2021) |