By Alton P. Chiu

Gunsite Academy is the oldest privately operated firearm training institution. Started by the legendary Jeff Cooper, this school prepares students for deadly force encounters rather than competitions. The competition-minded southpaw author attended a 5-day 223 carbine course (first of the series) with his Colt AR-15A2 carbine.

Knowledgeable instructors, detailed instructions and ample facilities provided information that cannot be gleaned by merely reading and practicing on “flat ranges.” While the author discovered gaps in his low-light and CQB skills, he expects every student to discover his own shortcomings and to leave Gunsite with the necessary redress. Here are some lessons learned.

The Mindset

A phrase often repeated by instructors was, “this is a fighting school.” “Diligentia, Vis, Celeritas” (“Accuracy, Power, Speed”) form the Gunsite triad. Since no two problems are alike and there is no cure-all, this course teaches “many ways to skin a cat” albeit with their own trade-offs.

Instructors induced stressors to ensure performance under pressure. Lower on the pressure scale, the same drills were not consecutively called in order to maintain vigilance. Higher on the pressure scale, the author experienced precipitous performance decline during the culminating exam. While satisfactory during warm-up practices, the author’s trigger control declined during time-pressured sessions, proving Gunsite wisdom: “Speed is the devil.”

As trouble travels in packs, students are constantly reminded to search and assess. Gunsite teaches that shooters should follow the target to the ground with a finger on the trigger in case the threat resurges, before sweeping laterally (finger off trigger) and repeating with every elevation change. Compared to a weekend course, 5 days afforded many repetitions to form new habits.

Stopping Threats

To effectively stop threats, one must balance speed with accurate shot placement to the upper chest or soft tissue area of head. The upper chest presents a larger area, but the effect is delayed. Soft tissue of the head (so named because eyes and nose offer an unfettered path to the brain) is significantly smaller with little margin of error, but the effect is instant. Inside 15 yards, the author felt confident aiming for the head at speed, even with iron sights. At 25 yards, he was more comfortable with speed and margins of the upper chest.

At “bad breath” distances, sight-height-over-bore means point-of-aim must be higher than desired point-of-impact. This holdover differs between rifles, optic configurations and zero distances to name some factors. Using the instructor’s recommended 50-yard zero (yielding less than 2 inches of deviation between point-of-aim and point-of-impact out to 200 yards), the author found the tabulated aiming references to work well with his AR-15-A2.

Manipulation

Gunsite Academy taught students to visually and tactilely confirm manipulations, such as loading and malfunction clearing, for both low-light use and safety assurances. The author interpreted this methodical approach to value certainties, purchased with some up-front time, to avoid surprises “for want of a nail.”

To build this certainty, magazines are pushed then pulled to confirm proper seating. To confirm proper feeding, if time permits, students are taught to remember which side of the magazine the top round resides; seat magazine; chamber; then withdraw magazine and confirm the top round shifted to opposite side. The author appreciated this technique not only for low-light but for rifles with deeply recessed ejection ports (e.g., HK MP5, FN F2000) that make “brass check” impossible.

When practising speed and partial magazine reloads (aka tac-load or reload with retention), the author experienced wrist fatigue. Mild fatigue prevented him from pointing the rifle at the threat while reloading; rotating it up and into his “workspace” eased burden but cost time. Severe fatigue prevented the magazine from seating during bolt-forward reloads, even with less-than-full magazines. To keep plodding on, the author placed his primary hand atop upper-receiver for leverage. While the author strengthens his wrists, he will ponder whether to lock the open bolt before reload as a general policy; he already observes this for HK G3 and MP5 as they lack last round bolt-hold-open. This exchanges the possibility of one (chambered) round for the certainty of a full magazine.

To clear malfunctions, Gunsite teaches immediate action drill (Push-Pull-Roll-Rack- Assess) with additional steps to clear double-feeds. Push-pull ensures seating; slap does not confirm seating and can cause top rounds to jump feedlips and further foul action if the bolt were stuck to the rear. Roll carbine until ejection port faces the ground; this eases egress of offending rounds. Rack to clear chamber. Assess situation, as it may have evolved such that shooting is no longer warranted.

A bolt not returning home during rack indicates double-feed, and one should first lock the open bolt, withdraw the magazine, insert a hand through magazine well to clear action, rack to clear chamber and finally reload. When the author unexpectedly experienced a double-feed, he visually identified it while his mind started taking shortcuts. After he fouled the sequence, all focus was directed at the rifle with no focus left for situational awareness. This experience illustrated the importance of a well-practiced and methodical checklist.

Being ambidextrous, the author switches shoulders when slicing corners to reduce exposure. The instructor pointed out that doing so rendered one unable to respond for the duration (about two seconds) if a threat unexpectedly presents itself. As a testament to instructor caliber, Gunsight also taught the author an impromptu lesson via learning-by-doing: if one intends to shoot ambidextrously, one should be equally proficient at shooting and manipulating from either shoulder. When the author was shooting from support-side (right), instructor unexpectedly called various reload

and malfunction drills. While fumbling, the author learned that placing all magazines on his right side meant none were at hand for a right-handed reload. As such, he supported his rifle with his left hand on the handguard so the southpaw manual-of-arms can be used.

Shooting Positions

For brevity, this section only covers a few tips. One such tip concerns how to quickly mount a rifle from low-ready: place buttstock toe high up into shoulder pocket such that comb contacts chin for a touch index. This helped the author consistently acquire proper sight alignment and sight picture, yielding faster reaction times and more accurate shot placements.

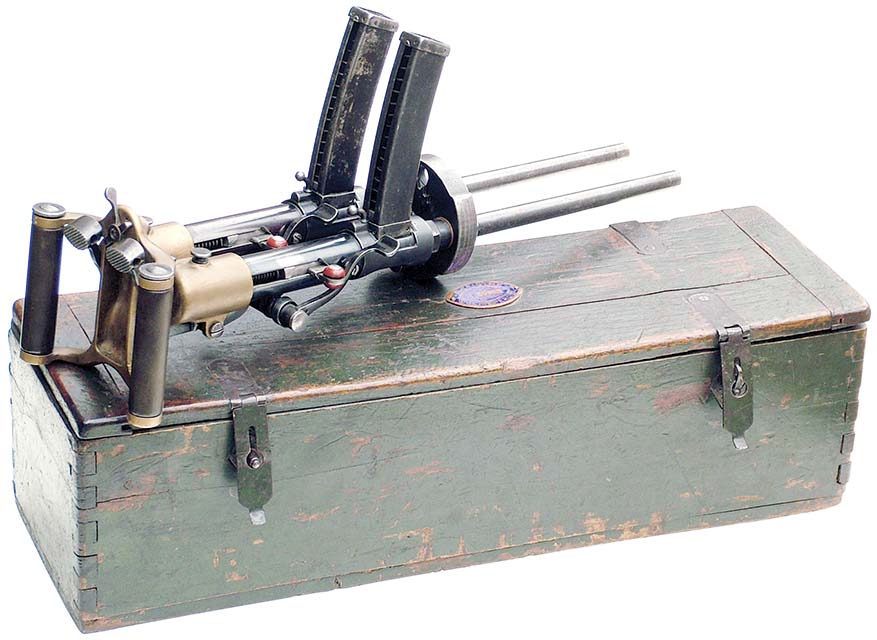

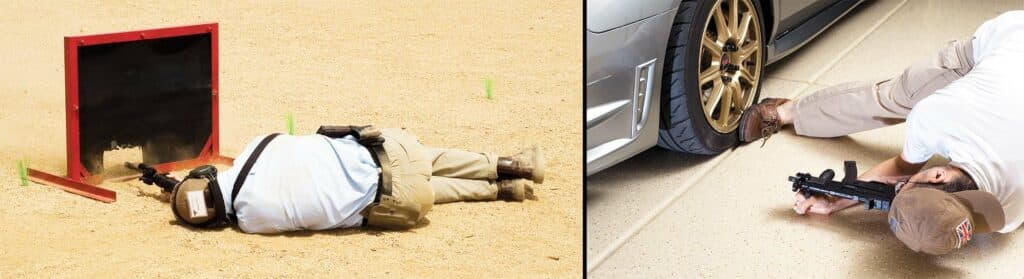

Decidedly unconventional positions where a rifle is rotated 90 degrees (ejection port facing sky or ground) were introduced for use in urban environments or VTAC barricades common for many matches. To shoot over low cover (e.g., high roadway curbs, low flower beds), students learned supine prone. Lying on the back, students rolled toward the target just enough for rifles to fire over cover. To shoot through low openings, urban prone rotates a standing position orthogonally so the spine parallels the ground with the rifle merely inches off terra firma. Support hand is balled under handguard for support. Although not covered in class, the lower body can be further tucked behind cover such as a brake disc and rim to shoot under vehicles. The author also found success adopting this position for use with the bottom row of a VTAC barricade. In contrast, SBU prone adopts a traditional prone position with shoulders square to target, but the rifle is turned sideways and placed over shoulder to shoot through lateral slats such as those on a second-to-bottom row of a VTAC barricade. Also not covered, the same upper body position reused in kneeling allows one to shoot over vehicles with minimal head exposure; rifle rotation places bore at same elevation as the eye. With all three positions, sight-height-over-bore induces lateral offset which must be learned through practice. This course only afforded one practice session for these positions.

For the outdoor-minded student, instructors discussed impromptu rifle support on vertical and horizontal surfaces familiar to Precision Rifle Series shooters. Outdoor Scrambler and Military Crest outdoor simulators provide ample opportunities for practice. Many other instructions are not mentioned here for brevity, but all are eminently useful and well worth the price of admission.

Low-Light Exercises

The course included an evening session to introduce low-light shooting. As twilight did not start until around 19:30 during summer, the session was limited to roughly 90 minutes (hampered by range limitations). Instructors discussed handheld light features and stressed simplicity in operation.

Exercises during twilight, without illumination, showed limits of human vision and iron sights. Targets featured a black sweater and drawn revolver; the former made the black front sight post all but invisible while the latter proved difficult to identify past 7 yards. Since identification is a necessary precursor to engagement, this illustrated the attacker’s advantage and likely engagement distance.

After darkness fell, the instructor stood behind students and swept his flashlight across them to simulate vehicle headlights, allowing a fleeting engagement. The author’s own backlit shadow obscured the front sight post, but he muddled through with body indexing, thus proving the worth of tactile memory. However, electro-optics would drastically improve matters.

As befitting an introductory-level course, only handheld lighting techniques were discussed. Flashlights are common household items and are normally carried by prepared individuals as part of their daily kit. Even when equipped with weapon-mounted lights, handheld techniques are useful in case of malfunctions.

Harries technique for rifles is analogous to that for pistols. An arm with light forms an “iron bar” that pulls against rifle magazine well, preferably at a point closer to the elbow than the wrist for strength. While this requires a bladed stance that leaves recoil-control wanting, the author found thumb activation of light intuitive and sight picture stable.

The SureFire technique pinches the light between index and middle fingers of the support hand while bracing the tail switch against a vertical surface (e.g., magazine well or vertical foregrip) for weapon support. Curling one’s fingers towards the palm activates the light.

The author found superior stability and recoil control, but one of his lights gave inconsistent activation. Pelican 2360 featured a low-profile tail switch; this required precise placement when pulled against a flat AR-15 magazine well in order to activate. A convex thumb pad or ribbed magazine (e.g., “Circle 10” magazine for Arsenal SLR-106 as pictured) provided reliable activation. In contrast, the Pelican 1910 tail switch protrudes further and activates reliably with this technique. It should be noted that lights with shrouded tail switches (e.g., SureFire Aviator) are incompatible with this technique.

This session’s farthest distance was 15 yards, presumably to accommodate lights with low output and/or reach. The author’s two-AA-powered Pelican 2360 casts a spot beam with little spill, trading situational awareness for farther reach. His one-AAA-powered Pelican 1910 casts mostly a flood beam with short reach. His weapon-mounted, two-CR123-powered, SureFire X300 Ultra has significantly brighter output with a wide spot beam that amply covers a torso at these distances; there is abundant spill for situational awareness as well. Note that the X300, designed for pistols, trades reach for wider spot beam and more spill when compared to the rifle-oriented Scout series. The light was mounted to front sight block via Midwest Industries MCTAR-04.

Readers are encouraged to experiment in a safe environment to find their own preferred technique. Facilities that allow night-time shooting are scarce, and indoor ranges with dimmed lights may be a useful substitute.

Indoor CQB / Room Clearing

The essential lesson learned regarding single-person CQB is to avoid it altogether unless there is an overwhelming imperative such as family member in imminent danger. While the author learned a great deal about footwork and path planning, he was disconcerted by the inevitable exposure to uncleared spaces.

This course taught the proper way to slice corners. One should take small lateral side-steps until the edge of a potential threat is seen. Then, without pause, lean out to assess and engage if necessary. To avoid crossing one’s feet and failing to lead with foot closest to corner, one should lead with left foot when slicing left. In addition, do not move back behind cover when a potential threat is seen; this allows the threat to aim in with disastrous consequences.

Instructors emphasized proper path planning to reduce uncleared spaces into manageable problems; although there are still inevitable “soup sandwiches” that illustrate why single-person CQB should be avoided. Students learned to approach doors from knob side, open authoritatively, then step back and slice corner as described above. Approaching from hinge side is not ideal, as feet or a shadow visible through gaps can alert threats and allow them to aim in. Another imperative is to properly plan footwork and a path for the entry itself. Lining up parallel to a wall and leading with the foot closest to the wall, move directly to opposite deep corner. Since average doorways (“fatal funnel”) require two steps to transit, it gives time to assess and address threats in the deep corner. On the third step, feet are properly positioned for pivoting toward the other deep corner while assessing the rest of the room.

Gunsite shoot-houses provide scenarios for putting lessons into practice. The author learned that he moved too fast; when combined with fixating on one uncleared space, he was caught off guard by another threat. Additionally, he forgot about sight-height-over-bore when leaning around cover, so projectiles impacted the door frame and deflected from point-of-aim. His liberal expenditure of ammunition, combined with his forgetting to perform partial-magazine reloads, led to an empty rifle while engaging multiple targets. As he had practised his pistol transition without incorporating movements, he also didn’t move during the scenario despite kneeling to reduce his profile behind a dinner table. These lessons alone are well worth the tuition. To remedy these shortcomings, the author practices with multiple magazines loaded with a small and random amount of ammunition to force unexpected reloads or pistol transitions.

Threat identification is a vital, but little practised, part of deadly force encounters. Most “flat-range” sessions, including competitions with no-shoot targets, only exercise the Act part of the Observe-Orient-Decide-Act loop. The author discovered this deficiency during the shoot-house scenario: his observation and decision time felt slow and required mental focus instead of being an instinctive action. Indeed, he failed to properly identify a suicide bomber (requiring a headshot) under pressure of multiple target engagements. Other students indicated this to be a common theme. A remedial drill would be posting targets with different numbers and having a partner call a random number; the trainee must search for and engage the correct number.

This course only afforded one shoot-house scenario. For a “real world” application, the author surmises there is higher likelihood in clearing a room than shooting 100 yards. A shoot-house offers unique training opportunities not available elsewhere due to range constraints; the author learned important lessons in this scenario.

Colt AR-15A2

Overall, the AR-15A2 did not experience major deficiencies throughout the entire course. A2 iron sights were not an insurmountable handicap. For headshots up to 15 yards, the rear aperture could be ignored if the mount were consistent. At 25 yards, the author required the proper front and rear sight alignments to achieve good results; electro-optics, such as red dot sights, could alleviate this. At 100 yards, the author found more success with the small aperture than the large one. With no time pressure, he was able to produce similar group sizes with both, but the large aperture produced impacts almost 1 foot lower. At further distances, he had trouble focusing on the front sight; however, instructors’ coaching built his confidence using the iron sights.

A light (aka A1) profile barrel, comparable to other service rifles such as AK-74 (5.45x39mm) and G36 (5.56x45mm), reduced weight and made long shooting sessions enjoyable. The author did not experience point-of-impact shifts attributable to thermal effects, as any were masked by shooter error. Of the three broad-categories of barrel profiles tabulated, the author favors light profile for carbines as it staves off fatigue and quickens target transitions. While profile affects thermal properties and accuracy potential, it is only one of many factors in the complicated relationship (see Chiu, Alton. “The ‘Proof’ Is in the Precision Proof Research Carbon Fiber Barrel.” Small Arms Review, Vol. 23, No. 7, pp. 50–55).

The author used his Geissele Hi-Speed National Match two-stage trigger installed with “DMR” spring set for a 3-pound first stage. Second stage was set at 8 ounces and creep removed with internal adjustments. This provided predictable trigger breaks on-demand, affording precision in unstable positions or elevated heartbeat. The author credits this trigger with completing the outdoor scrambler fastest in his class (67.2 seconds with all first-round hits), earning him a Gunsite challenge coin.

Final Thoughts

Gunsite’s professional and always cheerful instructors facilitate absorption of material developed with a combative mindset. As a competition-minded shooter, the author found many topics illuminating. However, 5 days aren’t enough to introduce, much less master, materials, and he would have liked more shoot-house scenarios. He sincerely believes students of all skill levels will find this course enlightening and fun.

For more information, see gunsite.com.

| Distance (yards) | Point-of-Aim |

| 3 | Scalp |

| 15 | Between scalp and eyebrow |

| 25 | Eyebrow |

| Profile | Under Handguard | Forward of Gas Block | Nominal Weight for 16in Barrel (with extension only) |

| Light A1 | Thin | Thin | 1.4lb, 623g |

| M4 or “Government” | Thin | Thick | 1.8lb, 794g |

| Heavy SOCCOM | Thick | Thick | 2.1lb, 936g |

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V23N9 (Nov 2019) |