By Johanna Reeves, Esq.

Foreign Trade Zones–An Invaluable Tool for International Trade

In 1934, Congress passed the Foreign-Trade Zones Act (19 U.S.C. §§81a-81u) (as amended, the “FTZ Act”) to stimulate economic growth and development in the United States. The underlying logic was that American competitiveness in the global marketplace would be promoted if U.S. companies are encouraged to maintain and expand operations in the United States. The foreign trade zone (FTZ), by providing tariff and tax relief, was seen as an invaluable tool to remove certain disincentives associated with manufacturing in the United States. For example, a U.S. manufacturer is at a distinct disadvantage to foreign competitors when it has to pay higher rates on imported parts, materials or components to be used in the manufacturing process. By assessing duty on products made in a zone rather than on the individual parts, materials or components, the FTZ helps correct the imbalance.

Arguably, FTZs are still underutilized despite the many advantages. Perhaps this is due to a perception that the application process and review time effectively puts FTZs out of reach for most businesses. To address this, in 2009, the Obama Administration introduced critical changes to the FTZ program to broaden access to U.S. businesses through a new alternative site designation and management framework, known as the Alternative Site Framework (ASF).

This article will explore the FTZ program and regulatory oversight, FTZ uses and the important changes implemented pursuant to ASF that should continue to improve U.S. business access to FTZs because of more user-friendly regulations and a more streamlined administration of zone applications. In light of the recent tariffs the Trump Administration imposed on steel and aluminum imports into the United States, FTZs may indeed be the focus of a renewed interest.

I. The FTZ Program and Regulatory Oversight

An FTZ is a specifically defined secure area within the United States, typically located within 60 miles of ports of entry, that is treated as if it is outside U.S. borders for customs entry purposes. There are significant advantages to using an FTZ, namely the ability to enter items in duty-free status until withdrawn for consumption in the United States. Goods may be stored indefinitely, and exports from FTZs are free of duty. The following activities are generally permitted in zones: storage, disassembly, repackaging, assembly, sorting, cleaning, grading and mixed with other foreign or domestic merchandise. With formal approval from Customs, goods may also be exhibited, manipulated, manufactured or destroyed.

Pursuant to the FTZ Act, there are two agencies that have jurisdiction in the FTZ program: the Foreign Trade Zones Board (FTZ Board) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). The FTZ Board, through its regulations in Title 15 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Part 400, governs the establishment, modification, management and administration of zones. CBP is charged with supervising the zones, which includes controlling how merchandise is moved into and out of a zone and ensuring the zone procedures are in compliance with the FTZ Act and its implementing regulations. CBP’s regulations are in Title 19 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Part 146.

There are two types of FTZs: general-purpose zones and subzones. A general-purpose zone is an industrial park or port complex operated as a public utility. A subzone is a special-purpose FTZ established as part of a zone project for a limited purpose for a business or operation that cannot be accommodated within the general-purpose zone.

To establish a zone, written application is submitted to the FTZ Board, which is comprised of the Secretary of Commerce and the Secretary of the Treasury.

By approving an application to establish a zone, the FTZ Board grants authority to the applicant to establish, operate and maintain the zone. The grantee may apply to the FTZ Board for authority to establish a subzone or to expand or modify the zone project. The grantee may also enter into a contract with a private entity to operate the zone (the “Operator”), subject to approval from the port director. Some examples of FTZ grantees are: the Las Vegas Global Economic Alliance (FTZ No. 89, Clark County, Nevada); The Pease Development Authority, Division of Ports and Harbors (FTZ No. 81, Portsmouth, New Hampshire); Cleveland Cuyahoga County Port Authority (FTZ No. 40, Cleveland, Ohio); and South Carolina State Ports Authority (FTZ Nos. 21 and 38, Dorchester County and Spartanburg County, respectively, South Carolina).

Getting a zone up and running is not complete at this stage. In order to begin operations, the zone must be activated through CBP. The zone grantee or third-party operator must submit a written application to the port director within which the site is located, or which is closest to the Board-approved zone. The area to be activated may be all or any portion of the zone. The application consists of a detailed description of the site, operations to be performed within the zone, the type of merchandise to be admitted and fingerprints of the grantee or operator or its officers and managers, if requested by the port director. The application must also include written consent of the zone grantee, blueprints of the area to be activated and a procedures manual describing the control and recordkeeping system to be used in the zone. The procedures manual must be certified by the zone grantee or operator to meet the applicable regulatory requirements. Once CBP approves the application, the zone grantee or third-party operator must execute an Operator’s Bond. If the port director accepts the bond, operations may commence in the zone.

Another important definition is “User,” which is a corporation, partnership or person who uses a zone under agreement with the grantee or Operator. It is usually the User who applies to CBP for approval to admit, process or remove merchandise from the zone. In subzones, the Operator and User are usually the same entity.

There are approximately 250 general-purpose zones and 500 subzones in operation across the United States. Each of the 50 states and Puerto Rico has at least one general purpose zone. More than 3,000 companies take advantage of the FTZ program. A current list of FTZs organized by state is available at https://enforcement.trade.gov/ftzpage/letters/ftzlist-map.html. The list includes the address and phone number of each grantee.

II. What Can Be Done in An FTZ?

A variety of activities are authorized for FTZs, including assembly, exhibition, cleaning, manipulation, manufacturing, mixing, processing, relabeling, repackaging, salvaging, sampling, storing, testing, displaying and destruction. The purpose of allowing such activities to occur in an FTZ is to encourage business operations in the United States that would otherwise have been conducted abroad for customs-related reasons, such as payment of duty or excise tax. Additionally, items may be exported from an FTZ free of duty and excise tax.

The FTZ Board may prohibit or restrict activity in a zone to protect the public interest, health or safety. In addition, many products subject to an internal revenue tax may not be manufactured in an FTZ. For example, firearms and ammunition subject to the Firearms and Ammunition Excise Tax (FAET) may not be manufactured in an FTZ. It is important to note that retail trade is also prohibited in zones.

III. FTZs and Customs Bonded Warehouses

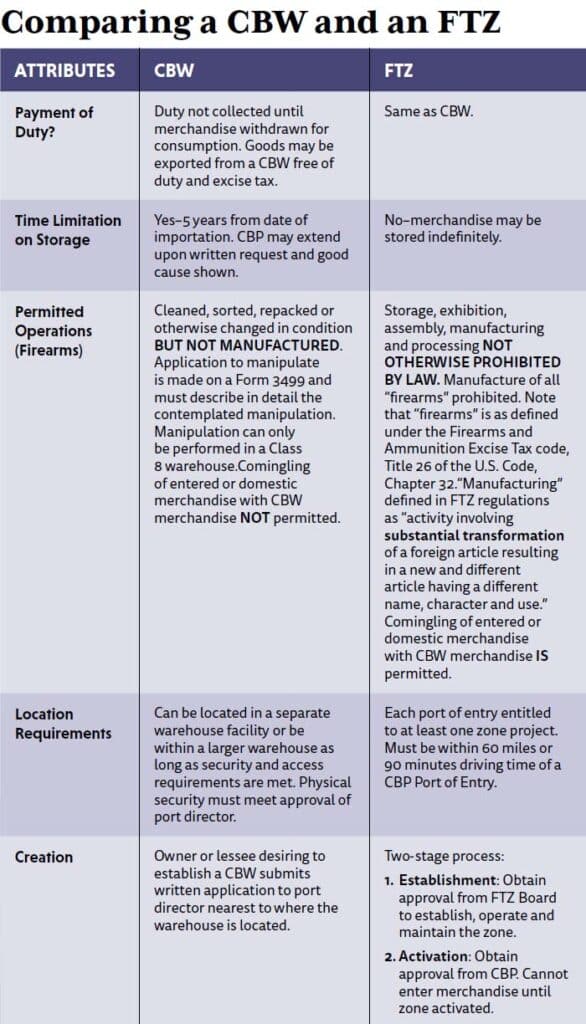

An FTZ is different from a Customs Bonded Warehouse (CBW) in a variety of ways. A CBW is a building or other secured area in which imported dutiable merchandise may be stored, manipulated or undergo manufacturing operations without payment of duty, but only up to 5 years from the date of importation. Like an FTZ, duty is not collected until the merchandise is withdrawn for consumption. However, a CBW must be bonded, which is no less than $25,000 on each building or area covered by the bond. The port director determines the bond amount based on the purpose for the bond. Authority for establishing a CBW is in Title 19, United States Code (U.S.C.), section 1555, and the regulations outlining the requirements for the operation of CBWs are found at 19 CFR 19. CBP provides additional information on establishing CBWs on its website at: https://help.cbp.gov/app/answers/detail/a_id/371/~/establishing-a-customs-bonded-warehouse.

The table provides a quick comparison of an FTZ and a CBW.

IV. The Alternative Site Framework

Establishing an FTZ is often seen as a slow, complicated and cumbersome bureaucratic process, taking anywhere from six months to a year or more and only if the FTZ Board deems the zone or subzone to serve the public interest. For a general-purpose zone, an application must be supported by special act of the state legislature and evidence the corporation is chartered for purposes of establishing a zone. The FTZ Act requires that the FTZ Board grant an application if it determines “the proposed plans and location are suitable for the accomplishment of the purpose of a foreign trade zone … and that the facilities and appurtenances which it proposed to provide are sufficient …” (19 U.S.C. §81g).

The FTZ Board considers several factors in determining whether to grant authority for a zone. For example: the need for zone services at the proposed location, existing and projected international trade-related activities, employment, adequacy of operational and financial plans and extent of state and local support. The FTZ Act requires preference be given to public corporation applicants, such as state or municipal instrumentalities. Corporations are able to submit applications but must be qualified to apply for a zone grant of authority under the laws of the state in which the zone is to be located. If an application is not the first for an FTZ at the CBP port of entry, then the applicant must demonstrate why the existing zone(s) “will not adequately serve the convenience of commerce” (i.e., is unable to meet the applicant’s FTZ-related needs).

The FTZ Board takes an average of 10 months to process a site application.

In 2009, the FTZ Board adopted a proposal for an Alternative Site Framework (ASF), which revolutionized the FTZ program and made it more accessible to U.S. businesses by implementing a more streamlined site application process. An ASF can have a broader service area than a traditional zone, with one or more jurisdictions (most often counties) in which FTZs may be established. The ASF allows for a limited number of “magnet sites” (typically six) intended to serve or attract multiple operators or users under the ASF. Companies still apply to the FTZ Board for a “minor boundary modification,” but it is a simplified process, and applications may be approved within 30 days.

The implementation of the ASF brought renewed vigor to the FTZ program. Zones that have reorganized under the ASF have seen increased interest in international trade, especially among smaller companies. Through the ASF, companies can enter into the FTZ program without having to jump over complicated and lengthy regulatory hurdles.

It is important to note the ASF is optional, and a grantee must apply to the FTZ Board to establish a new zone under the ASF or to reorganize its existing FTZ under the ASF. Unless and until a grantee reorganizes its existing FTZ, the zone will continue to operate under the traditional framework. A list of FTZs organized under the ASF is available at: https://enforcement.trade.gov/ftzpage/letters/asflist.html.

V. Conclusion

There is no question FTZs can offer valuable benefits to help offset some of the challenges inherent with importation of firearms, ammunition and other similar defense articles. The deferral of Customs duties, unlimited storage time and the ability to undertake certain operations inside the FTZ are only some of the advantages an FTZ user may enjoy. In light of the recent tariffs President Trump imposed on steel and aluminum, the importance of FTZs should not be overlooked. And as more zone grantees apply to reorganize their zones under the ASF, more companies assuredly will get involved with the FTZ program. FTZs are indeed an invaluable tool for international trade.

The information contained in this article is for general informational and educational purposes only and is not intended to be construed or used as legal advice or as legal opinion. You should not rely or act on any information contained in this article without first seeking the advice of an attorney. Receipt of this article does not establish an attorney-client relationship.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Johanna Reeves is the founding partner of the Washington, D.C., law firm Reeves & Dola, LLP (www.reevesdola.com). For 15 years she has dedicated her law practice to advising and representing U.S. companies on compliance matters arising under the federal firearms laws and U.S. export controls. Since 2011, Johanna also has served as Executive Director for the F.A.I.R. (FireArms Import/Export Roundtable) Trade Group (http://fairtradegroup.org). In 2016, Johanna was appointed by the U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Political-Military Affairs to serve on the 2016-18 Defense Trade Advisory Group (DTAG). Johanna can be reached at 202-683-4200, or at jreeves@reevesdola.com

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V22N6 (June 2018) |