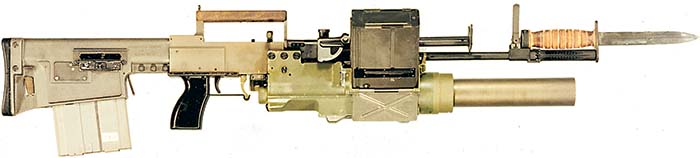

Right side of the Phase I SPIW from Springfield Armory with the full complement of equipment for firing 60 rounds of point-target XM144 flechettes plus 3 rounds of area-fire 40mm grenades, with biped and bayonet. The ingenious double box magazine, featuring two 30-round stacks one behind the other, is described in the text.

By R. Blake Stevens

The APHHW Becomes the SPIW: Point and Area Fire Now Specified

By January of 1962, a set of formal military specifications for a flechette-firing weapon had been prepared and submitted to the Office, Chief of Ordnance (OCO) for approval. The specifications superseded the short-lived APHHW nomenclature with a new name for the project: the Special Purpose Individual Weapon; the SPIW.

In these specifications one important main addition was made to the original burst-fire flechette weapon concept: the new SPIW was to combine the point-fire characteristics of the flechette-firing APHHW with the area-fire potential of a weapon like the recently introduced M79 grenade launcher.

On March 22, 1962, the OCO approved the detailed forecast for the development of the SPIW. The object was to, “provide the individual soldier with a weapon system possessing the capability to engage point and area targets to a range of 400 meters.” The forecast ended by confidently predicting that the SPIW would be type classified “Standard A” by June of 1966.

Terminating the M14 Program: An “Acceptable” Risk

Scant months later all M14 rifle production was abruptly halted, and contracts with the three hapless civilian M14 producers, Winchester, H&R and TRW, were brusquely abrogated. As stated in U.S. Rifle M14,

… [M14] Production at Springfield Armory was scheduled to be phased out first, by September, 1963. All three commercial producers wound down in the first quarter of 1964, amid very bitter and acrimonious comment to the effect that the immense amount of time, energy and money invested in good faith in the M14-manufacturing “learning curve” had all been wasted.

Meanwhile, as America’s military involvement in Vietnam escalated dramatically in the middle sixties, a worried U.S. Senate Subcommittee again queried the Secretary of the Army, Cyrus Vance, about America’s shoulder rifle policy for the immediate future. With implicit reliance in the forecasts of his systems analysts and theoreticians, Mr. Vance testified: “Termination of production of the M14 prior to the availability of SPIW involved certain risks which, after consideration by the Army, are deemed acceptable.”

All the tests by all the agencies over the preceding two years had concurred that the SPIW concept was technically feasible, and that the approach to its development was logistically sound. Heartened by this response, the Army confidently accelerated the SPIW’s adoption date by a full year, to June of 1965.

Choosing the Four Contractors

By December 1962, ten formal written SPIW development proposals had been received from industry. Each posited a completely different design, but all ten promised an on-time and reliable hand-held point-and-area-target weapon which would meet the specifications. In February, 1963, contracts were awarded to two soon-to-be former M14 rifle producers, the Harrington & Richardson Arms Co., and Olin’s Winchester-Western Division. The third and fourth designs that were chosen already had head starts at both the soon-to-be-renamed AAI Corporation (formerly Aircraft Armaments Inc.), and at Springfield Armory.

What the “SPIW Must Do”

Some salient characteristics excerpted from the carefully prepared SPIW Technical Data Package (TDP), which was supplied to each potential contractor to govern their manufacture, read as follows:

The weapon shall:

… Be of minimum weight… the loaded weight including a minimum of three (3) area type rounds and sixty (60) point type cartridges excluding other accessories shall not exceed ten pounds.

… Be capable of shoulder firing without undue discomfort from recoil or blast.

… [Produce] no hazard from ejected particles to personnel…

Reading over just the few characteristics quoted above, one can begin to understand the enormity of the gulf that has historically separated weapons designers from those who think up the specifications. Those searching for the SPIW project’s Achilles’ heel need look no further: the mutually-exclusive requirements of great complexity within stringent weight and size limits effectively locked each competing contractor into an arcane series of trade-offs and compromises, virtually insuring the ultimate failure of the program right from the outset.

In an interview with the author, retired Springfield Armory engineer Fred Reed summed this up bluntly as follows: “The SPIW was the first of the programs to be doomed from the start by ridiculous specifications.”

The Four First-Generation Firing Models

Difficulties notwithstanding, firing models of each of the four competitors’ first-generation SPIWs were duly delivered for examination and trial in March of 1964, only one month behind schedule. Three of the four were subjected to a variety of tests throughout the summer. The fourth design never even made it to the firing trials; it was rejected almost immediately as being far too heavy, and unsafe.

The H&R SPIW and the Dardick Triple-Bore Tround

The H&R SPIW earned the dubious distinction of being the only contender of the four to be rejected out of hand as “dangerous to shoot.. It was built around an exceedingly ill-conceived refinement of the revolving open chamber principle, which had previously been unsuccessfully offered on the commercial market in pistol form by its inventor, Mr. David A. Dardick. Working for H&R on the initial phases of that firm’s SPIW project, Mr. Dardick adapted the special triangular plastic cartridges his pistol had utilized, called Trounds, to contain three of the standardized AAI flechette-and-sabot projectiles, grouped around a central primer and powder charge. The result was called the “5.6x57mm triple-bore Tround.”

In the Dardick/H&R SPIW, the only reciprocating part was a top-mounted gas piston, which cammed a revolving cylinder 1200 (a third of a turn) with each fired shot. The three open-sided chambers in the cylinder thus successively picked up the leading round of a belt of the taped-together Trounds from a drum magazine suspended below the standing breech, positioned it for firing, and then released the spent case, still in its plastic belt, down the other side of the weapon. When the chamber containing a live Tround was in the firing position, all three of its flechettes were automatically lined up with a triangular cluster of three smooth bores, which had been drilled in the weapon’s ponderously front-heavy steel barrel.

In the open chamber concept, the body of each plastic Tround itself plays a much more crucial part in containing the forces of the explosion than does a conventional cartridge case, completely supported in a normal chamber. Initial function firings of the H&R SPIW had produced excess bulging and splitting in the Trounds due to variations of only a few thousandths of an inch in the plastic tape which surrounded each Tround.

Another immediate and fundamental problem concerned the three-shots-at-once theory. The three “barrels” were in fact one common space: every time the H&R was fired, gas leakage began as soon as the flechettes left their Tround. The first flechette exiting the muzzle triggered a further dramatic drop in pressure. At best, this reduced the muzzle velocity and consequently the range and accuracy of the other two flechettes. At worst, the pressure drop just might leave one or both of the remaining flechettes stuck in their respective bores, waiting to act as a serious obstruction when the next shot was fired.

In any event, the H&R SPIW package weighed in loaded at a ludicrous 23.9 pounds: the specification, it will be remembered, read a maximum of ten. Examining officers at Aberdeen’s Development & Proof Services promptly turned thumbs down on any further testing of any part of the H&R SPIW design.

The Olin (Winchester) Soft Recoil SPIW

Firing the conventionally-primed Springfield XM144 5.6x44mm flechette cartridge, the recorded muzzle velocity from the Winchester’s 20-inch, non-chromed smoothbore barrel was 4,585 fps. The weapon weighed twelve-and-a-half pounds fully loaded. The rate of fire was around 700 rpm for both full-auto and burst modes of fire.

The innovative blow-forward grenade launcher was the only feature of the Winchester design to survive the phase 1 selection process. The point fire portion of the weapon was judged unsatisfactory. Indeed, it was discovered that the very advantages claimed for the “soft recoil” concept were difficult if not impossible to obtain when teamed with the Winchester’s low rate of fire: a recoil housing many times longer than that provided would have been necessary in order that a three-shot burst could be fired at 700 rpm before the recoiling parts abutted the rear of their housing and transmitted the recoil impulse to the shooter.

The Olin (Winchester) SPIW was consequently abandoned, but the blow-forward launcher was developed further under contract for the Springfield SPIW team, in favor of the Armory’s own initial launcher design.

The Springfield Armory Bullpup SPIW

If the first two candidates mentioned above were quick disappointments, the remaining two were not. Indeed, it is ironic in the extreme to consider that the Phase I weapons fielded by AAI and especially Springfield were prototype designs, which sprang in their complexity virtually from nowhere in terms of predecessors, and yet in some ways their performance was never surpassed or even matched in the following six, expensive years.

Aberdeen described the 1964 Springfield bullpup SPIW as “a conventional gas operated system which fires the XM144 cartridge. Main portions of the mechanism are housed in the butt stock.” The rifle fired from a 60-round double-box magazine and was gas-operated (conventional gas piston), with a front-locking, rotary bolt.

The Springfield point target magazine serves very well to illustrate the ingenuity of design born of sheer desperation that was to become the rule rather than the exception during the SPIW program. Springfield’s solution to the 60-round capacity specification combined two thirty-round, double-column stacks, one behind the other. (It was here that the bullpup concept came to the rescue, providing the least awkward place to mount such a box-like device.. In firing, the reciprocating bolt stripped rounds off the leading stack until it was empty and the follower appeared. This freed a device that had been depressing the rear stack of cartridges, allowing them to rise into the path of the bolt. The rear magazine had no feed lips as such: the bolt first slid the top round from the rear magazine forward onto the follower of the empty front one, and then fed it up into the chamber.

The designer in charge of development of the 1964 Springfield bullpup SPIW was Mr. Richard Colby. He had not chosen the unique double magazine design frivolously. Feeding sixty rounds of even the small, lightweight XM144 flechette cartridges from a single double-column stack had proven to be an impossible task: no magazine spring that could be reloaded by hand would provide enough lift fast enough to have the next round of a full magazine ready for feeding during 1,700 rpm burst fire. This is not to mention the fact that calculations for such a magazine revealed that it would be so long and unwieldy as to make shooting from the prone position impossible.

Both Winchester and, as we shall see, AAI answered the first-generation 60-round point target capacity requirement by using drum-type magazines, but in so doing both firms encountered many new and serious frictional forces inherent in a rotary feed system. This led to chronic feeding problems and consequent unreliability, which in Olin’s case contributed to the demise of the whole Winchester SPIW program. It is noteworthy that the point target ammunition capacity specification was eventually relaxed to a more realistic fifty rounds, but not until the perfection of the sixty-round magazine had eluded a further two years’ expensive development.

The AAI Corporation Primer-Actuated SPIW

The 1964 AAI SPIW was 39.9 inches long overall and weighed eleven pounds unloaded, or 13.3 pounds fully loaded with the required sixty XM110 flechettes and three 40mm grenades. Muzzle velocity from the AAI’s 18-inch barrel-and-stripper was 4,820 fps, with an actual measured cyclic rate of 2,400 rpm on three-round burst fire.

A Note on Rates of Fire

It is worth commenting that both the Springfield and AAI SPIWs had answered the “salvo” requirement by featuring blisteringly high rates of burst fire. The rate of fire for the Winchester, which was by far the slowest of the first-generation SPIW submissions, was 700 rpm, which is just over eleven rounds a second. Burst and full-auto fire from the 1964 Springfield SPIW was measured at 1,700 rpm, which translates to over 28 rounds a second; while the AAI burst fire rate was 2,400 rounds per minute, or an astonishing 40 rounds per second.

Phase I Results

The results of the phase I Aberdeen D&PS examinations and that summer’s firing trials, which had taken place at Fort Benning from April to the middle of August, 1964, led to a curiously mixed reaction. Army Weapons Command remained solidly behind the SPIW as a concept, and the SPIW designers themselves had long since recognized and accepted most of the erratic, not to say startling, behavior of their brainchildren as necessary trade-offs in the desperate attempt to meet the specifications. Nevertheless, a bewildering array of problems in almost every conceivable area of the endeavor was documented by the test teams.

By November of 1964, when all the results were in, one thing was certain: the carefully-planned scenario leading to the adoption of a successful SPIW by the following June was out the window completely. Even phase II of the initial TDP, which had confidently envisaged a short period of full-scale engineering development for the successful phase I candidate followed by its limited manufacture for final troop trials, was itself now out of the question.

Regarding the summer’s simulated mass production runs of XM110 and XM144 cartridges, no economical way had been devised to fabricate a satisfactory flechette round in quantity. The contractors complained that every component required extraordinary care in manufacture and assembly in order to ensure a reliable round. This meant a great deal of costly and difficult-to-inspect hand-work on each cartridge.

In general, reported user dissatisfaction with the two finalist SPIW designs (Springfield and AAI) as weapons was lumped into three basic categories: poor reliability, poor durability, and excessive weight.

As for system durability, the exasperated designers grew weary of trying to explain to adamant AWC test officers that every conceivable ounce had been shaved from these complex weapons in an attempt to meet the weight requirement.

As it turned out, no SPIW ever came within the ten-pound-loaded, point- and area-fire weight limit. As the program continued, this official weight requirement was ignored as much as possible, with weights for the two halves of the SPIW system thenceforth discussed separately.

The Second Generation SPIW Plan

Many of the SPIW’s initially startling idiosyncrasies, which had been abruptly user discovered in the first generation trials, were already the subject of much AAI research. The AAI engineers felt strongly that effective remedies were not only feasible but just a matter of a little more time and R&D money. This attitude was at length adopted by AWC.

In a move that coincided with the March, 1965 deployment of American troops into the combat zones of South Vietnam, AWC approved a re-orchestrated, 35-month, two-phase SPIW development plan under which AAI and Springfield were both to develop and fabricate ten complete second generation weapon systems. There was one difference: “Standard A” status for the successful second-generation SPIW was rescheduled for March of 1968, a postponement of almost three full years.

Another interesting difference in the new plan was that the Army had turned thumbs down on any further development of the bullpup concept, which Springfield had emulated in 1964, or even a rifle with a separate pistol grip like the early AAI models. From now on, all SPIWs submitted were to feature what AWC considered to be the increased pointability of conventional rifles, like the M14, or, to give it its due, the 1964 Winchester SPIW.

The busy program at AAI contrasted sharply with the mood at Springfield, where following the 1964 trials the Armory engineers had received virtually no feedback regarding their first generation design. Reasons for this brusque treatment were not long in surfacing: in a further reorganization disguised as cost cutting, Defense Secretary McNamara had already announced the termination of Springfield Armory as an official agency, to be effective by April of 1968.

Improvements in Flechette Cartridges The Fatter Springfield / Frankford XM216

Springfield in particular had experienced difficulty meeting the velocity requirement with their XM144 cartridge; in fact the unofficial word is that they never quite did. Be that as it may, both contenders redesigned their cartridge cases for more powder capacity before entering the second generation competition. Thus, Springfield’s XM144 was presently superseded by a completely new round, the somewhat fatter XM216. Both the XM144 and the XM216 were fitted with the “Primer, Miniature, FA T186E1.”

The AAI XM645, with One-Piece “Anvilless” Piston Primer

AAI’s XM110 had already left its dimples behind, to become the slightly longer XM645. Both new rounds were loaded with AAI’s still-standard flechette-and-sabot package for the upcoming second generation trials.

AAI had in the meantime also developed an ingenious one-piece piston primer to replace the more complex and prohibitively expensive first-generation multi-piece design. The AAI one-piece piston primer was yet another remarkable product of the SPIW program, in that it was designed to function without an anvil. In other primers, whether Boxer, Bloehm or Berdan, it is the action of crushing the priming compound against the anvil that causes ignition. No such anvil was present in the new one-piece AAI primer design.

Interestingly enough, no one was really sure just how the AAI anvilless primer worked. Some thought the priming pellet, which contained about three times more primer mix than usual, slid a bit when the piston was pushed in, thereby striking itself alight like a kitchen match. (As part of the manufacturing process the priming mix was very heavily compressed: a note on the drawing reads “Primer mix is to be compressed within a compaction pressure range of 129,000 psi to 172,000 psi. Piston-primer size must not be altered as a result of the compaction operation.”)

Others felt that the restricting front collar acted like an anvil. Still others pointed to the roughened, or finely threaded, internal sides of the primer cup itself, positing that the specially-compounded priming pellet set itself alight as contact here was abruptly broken by the firing pin blow.

In addition to remodeling their SPIW along more conventional lines, AAI was to set up a simulated mass-production assembly line to produce 130,000 rounds of its new improved XM645 piston-primed cartridge. Production contracts for AAI’s second generation cartridge case, and for new one-piece piston primers, were first let at this time to the Canadian government ammunition facility Dominion Arsenals in Quebec (initial headstamp DA 65).

The Last SPIW from Springfield Armory

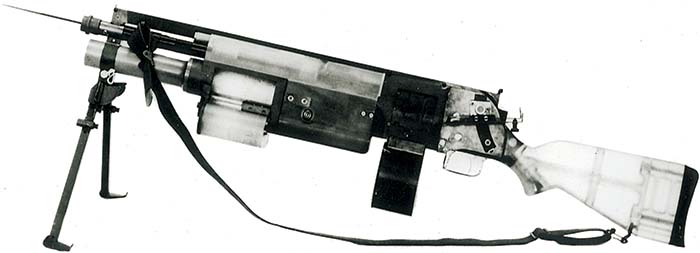

The 1966 Springfield SPIW was exactly 40” long and was chambered for Frankford’s new, fatter XM216 cartridge. The 60-round point target ammunition capacity specification was still in effect, and due to the conventional nature of the new rifle the longish, front-and-rear double magazine of 1964 had been reconfigured. It was now made of clear Lexan plastic and, in a further burst of desperate ingenuity, featured two thirty-round stacks side-by-side. Springfield’s Preliminary Operating and Maintenance Manual (POMM 1005-251-12) for their 1966 SPIW described the functioning of this novel magazine as follows:

The left cartridge stack is depressed by the stack release mechanism when the magazine is seated in the magazine well, while the right stack remains elevated in the stripping position. When the last round is stripped from the right stack, its spring actuated follower raises the cartridge retainer actuator into the path of the operating rod. After the operating rod moves rearward after [the chambered] round is fired, it cams the actuator and retainer to [the] left side, releasing the left cartridge stack to stripping position.

All in all it appeared that, although the Armory SPIW team had taken the project to heart and made it a labor of love, the very tight timing and funding constraints of Secretary McNamara’s termination order were very evident in this second generation Springfield design.

The AAI Second Generation SPIW

AAI’s SPIW program had by far the longest pedigree of any of the four original contenders, due to that company having originated the flechette concept in the first place. The mood at AAI was therefore one of determination and conviction: while a number of features on Springfield’s second generation gun were brand new and born of desperation, AAI’s were mostly refinements of early ideas, which already had a comparatively lengthy firing record.

A parallel program of redesign had resulted in a very well-conceived new plastic-stocked AAI SPIW prototype, which soon emerged fully engineered for second-generation production. The drum magazine and action stroke were both slightly longer in AAI’s 1966 model SPIW, due to the extra 4mm in the length of the new XM645 cartridge case.

Results of the Second Generation SPIW Trials

A second generation engineering design test was conducted by the Infantry Board at Fort Benning from August 26 to October 31, 1966. These trials, or more accurately, comparative evaluations, were in a word disastrous.

The one supreme flaw in the SPIW program still, which AWC had steadfastly refused to face or even consider right from the outset, was the gulf separating the specifications from what was humanly possible to design and construct. The Board’s report on the 1966 comparative SPIW evaluations contained clear indications that this gulf had again proven too wide and deep to bridge.

A Frank Assessment by Colt’s Robert E. Roy

Meanwhile, AWC was trying to find a civilian firm willing to continue the development of the Springfield SPIW, which was to receive no further funding at the Armory regardless of the outcome of the second generation trials: that bastion was being adamantly wound down in response to Secretary McNamara’s termination order. A meeting was therefore set up at Fort Benning in October, while the 1966 evaluations were still in progress, to demonstrate the second generation SPIWs to representatives of a selected few companies who had expressed interest in taking the Springfield project over.

The real if inadvertent importance of this AWC demonstration was that it provided some highly qualified but uncommitted outsiders with their first real look at the SPIW in action. Among those attending was Mr. Robert E. Roy, then the Engineering Project Manager for Colt’s Inc. Colt’s had purchased the rights to the AR-15 from ArmaLite back in 1959, and had since shrewdly piloted the “little black rifle” all the way to quasi-adoption in the U.S. Armed Forces. With America’s massive buildup in Vietnam went more and more Colt-made M16 rifles: Colt’s had more at stake than virtually anyone should the SPIW be successful. They therefore took a very sharp and direct interest in these proceedings. A saboted flechette load in the regular 5.56mm case already existed, for example, as did experimental smoothbored M16s.

The Infantry Board was necessarily constrained to report its findings exclusively in terms of the requirements, but Colt’s was not so restricted: Mr. Roy wanted to know how the SPIWs looked and functioned in a real-world sense. The bottom line was, how long did Colt’s have until the SPIW put the M16 out of business. Mr. Roy’s confidential report to his superiors, excerpted as follows, soon calmed any fears on that score:

… It appears to me that the SPIW system is still far from fruition as an operational weapons system. The “all things to all people” approach that has been used in setting requirements for this weapon has resulted in many problems that appear almost insurmountable, since many of the requirements are at odds with each other.

… The normal tendency when [the flechette] strikes flesh or bone is for the shaft to bend slightly and then to tumble. It is this property that makes such a small, light projectile lethal. When the flechette tumbles, it has lethality comparable with the 7.62 NATO. The flechette does not always tumble, however, and if it does not tumble, it has very little stopping power and a person might hardly know he is shot…

In order to keep SPIW ammunition as light as possible, cartridge cases have been made to the minimum size possible. This makes it necessary to use relatively slow-burning powders in order to get the necessary energy for full velocity. The result is very high pressures at bullet exit. I would estimate bullet exit pressures are in the order of 25,000 psi.

The noise and flash produced by these weapons is far in excess of the M14 or M16 and at least the equal of our M16 Commando submachine gun without the noise-flash suppressor. I have fired the AAI weapon, and it is definitely uncomfortable to fire without ear plugs.

Present plans call for design finalization by early 1968 and initial production by 1969. After looking at the hardware available, witnessing the firing, and firing the weapon myself, I can’t see how this schedule can possibly be met. SPIW is still an R&D effort and will require at least one more complete redesign, and the solving of several basic problems before it can be seriously considered as a military weapon.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V19N2 (March 2015) |