By Knox Williams –

Silencer. Suppressor. Muffler. Moderator. Can. All words to describe the same thing – one of the most misunderstood tools in existence. Within the gun world, there’s a tremendous amount of debate surrounding what they should be called. However, unlike clips and magazines, where they really are two different things, all sides have a leg to stand on when it comes to the name of these devices.

That’s because when they were invented around the turn of the twentieth century, the original inventor called them silencers. Federal law mirrors that, defining them as a “firearm silencer” or “firearm muffler.” My non-profit, the American Suppressor Association (ASA), chooses to call them suppressors because it’s the most accurate description of what they actually do. In England, they’re called moderators. Colloquially, we just call them cans. Feel free to call them whatever you want, but know this: the only difference between a silencer, a suppressor, a muffler, a moderator, and a can is word choice.

Hollywood

When you hear the word silencer, what’s your first thought? If you’ve never heard a suppressed gunshot in real life, I’d wager that in your mind’s eye many of you see (and hear) a small cylindrical device that renders gunshots completely inaudible. After all, that’s how suppressed gunfire is portrayed in the movies.

So, is Hollywood’s portrayal of suppressors accurate? No. Absolutely not. Not even close.

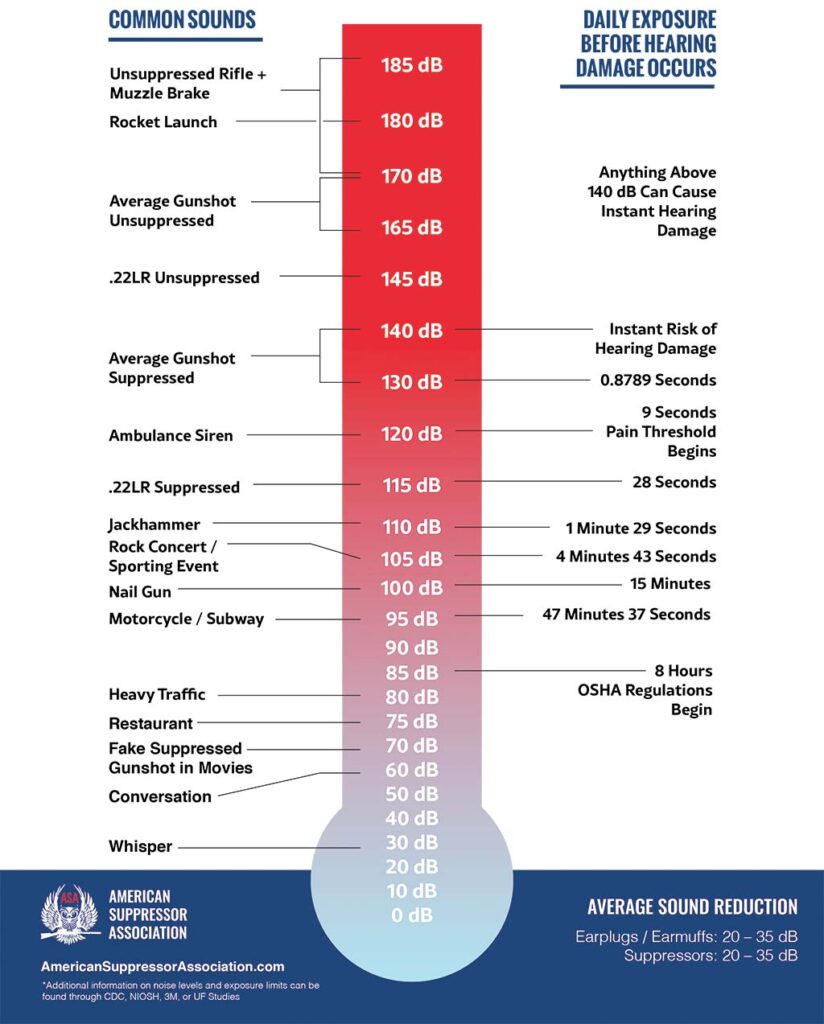

On average, suppressors reduce the signature of a gunshot between 20 to 35 decibels (dB), roughly the same attenuation as earplugs or earmuffs. Even the quietest suppressed gunshots are as loud or louder than a jackhammer striking concrete. Would you trust anyone who told you that a jackhammer is too quiet to hear? I think not.

A concept that many people don’t grasp is that seeing suppressors in a James Bond film doesn’t make them an expert on the topic. In the same vein, watching Jurassic Park doesn’t make someone a paleontologist. Like the dinosaurs found on Isla Nublar, the noise, or more accurately the lack thereof, that suppressed gunfire makes in movies is pure unadulterated fiction. It is designed to sell a story, not illustrate reality.

Hollywood exists to entertain. Their depiction of silenced gunfire, which is entirely fabricated in sound effects labs, is excusable because it is just a tool to help them tell their tales. Hollywood is unencumbered by the burden of truth; our political policy is not. At least, it shouldn’t be.

That said, Hollywood is not entirely to blame for the cavernous disconnect between the public perception of what suppressors can and cannot do. In some ways, silencers are a victim of their own initial marketing success. To understand why, we must first learn about their origins.

Invention of Silencers

The term silencer was coined by Hiram Percy Maxim, the man who patented the “Silent Firearm” in 1909. A prolific inventor, Maxim was born into a family of men whose creations changed the course of history. His father, Sir Hiram Stevens Maxim, invented the Maxim machine gun, and his uncle, Hudson Maxim, was an early inventor of smokeless gunpowder.

In Hiram Percy Maxim’s own words, “[t]he Maxim Silencer was developed to meet my personal desire to enjoy target practice without creating a disturbance. I have always loved to shoot, but I never thoroughly enjoyed it when I knew that the noise was annoying other people. It occurred to me one day that there was no need for the noise. Why not do away with it and shoot quietly.”

Maxim spent nearly two years working on prototypes before developing a concept that was able to significantly reduce the noise of a gunshot. Upon inventing the first commercially viable firearm suppressor, he incorporated the Maxim Silent Firearms Company in New York City, New York, in a building across the street from New York City Hall.

Marketing Magic

The business’s third catalogue, titled Maxim Silencers, promised customers the opportunity to shoot “without noise,” claiming that “[t]he Maxim Silencer annuls entirely the report of discharge.” Although the pamphlet goes on to state that the silencer “does not make shooting absolutely noiseless, for, of course, slight sounds can be heard,” the damage was already done. Maxim’s initial assertions serve as the genesis of the myths and misconceptions that haunt suppressors to this day.

Subsequent advertisements further solidified the notion that Maxim’s tool actually silenced firearms. For years, they echoed the claim that customers would be able to “shoot without noise” because the Maxim silencer “absolutely stops all the noise of the report.”

Contrary to Maxim’s claims, as well as popular belief, no tool will ever be able to make a gunshot silent. Outside of the context of shooting, nothing will even be able to make them quiet. Guns are simply too loud.

How it Works

When a gun is fired, a controlled explosion of gunpowder propels the bullet through the barrel. Once the bullet exits the barrel, these hot gases are rapidly released into the atmosphere. The result is the muzzle blast, one of several primary noise sources associated with a gunshot. This is also the only noise source that suppressors abate.

Suppressors work by trapping and disrupting these gases, allowing them to slowly dissipate. It’s the exact same science behind automobile mufflers, which should come as no surprise considering the muffler was another of Maxim’s early inventions. Interestingly, in the United Kingdom, mufflers on motorcycles are called silencers and silencers as we know them are called moderators.

In 1913, the Maxim Silent Firearms Company was consolidated into the Maxim Silencer Company, an offshoot business based in Hartford, Connecticut that Maxim formed to focus on his similar inventions: automobile, maritime, and industrial mufflers. Although they no longer make firearm suppressors, the Maxim Silencer Company still exists today.

Hearing Protection

So why does anyone need a suppressor? In two words: hearing protection.

We all know that guns are loud, but did you know that any exposure to unsuppressed gunshots without adequate hearing protection can instantly cause permanent hearing damage?

Sound pressure levels (SPL) are measured on a logarithmic scale, meaning that they increase in a nonlinear fashion. Every 3 dB increase doubles the sound pressure level; every 10 dB increase raises the SPL by a factor of 10. This means that 3 dB is twice as loud as 0 dB, the lowest threshold of human hearing. 10 dB is 10 times more intense, and 20 dB is 100 times more powerful. The following table illustrates the relationship between dB levels and the logarithmic scale:

Decibel Levels: 0 3 6 9 12 15 18 21 24 27 30 (+3)

Logarithmic Scale: 1 2 4 8 16 32 64 128 256 512 1024 (x2)

Other examples of commonly used logarithmic scales include the Richter scale for measuring earthquake intensity, and units used to measure the data storage capacity of computers.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) established recommended exposure limits (REL) for occupational noise exposure in 1998. Per the NIOSH REL, workers can safely expose their ears to 85 A-weighted decibels (dB[A]) for an eight-hour time-weighted average in a given day. The REL utilizes the equal-energy rule, so “for every 3-dB increase in noise level, the allowable exposure time is reduced by half. For example, if the exposure level increases to 88 dB(A), workers should only be exposed for four hours. Alternatively, for every 3-dB decrease in noise level, the allowable exposure time is doubled, as shown in the table below.”

Average Sound Exposure Levels Needed to Reach the Maximum Allowable Daily Dose of 100%

| Time to reach 100% noise dose | Exposure level per NIOSH REL |

| 8 hours | 85 dB(A) |

| 4 hours | 88 dB(A) |

| 2 hours | 91 dB(A) |

| 60 minutes | 94 dB(A) |

| 30 minutes | 97 dB(A) |

| 15 minutes | 100 dB(A) |

The Prescription for Hearing Safety

According to Dr. Michael Stewart, Professor of Audiology at Central Michigan University, “[t]he level of impulse noise generated by almost all firearms exceeds the 140 dB peak SPL limit recommended by OSHA and NIOSH.” For this very reason, he goes on to state that “it is not surprising that recreational firearm noise exposure is one of the leading causes of NIHL [Noise Induced Hearing Loss] in American today.”

In 2011, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was commissioned to assess the level of noise exposure for federal government agents at an outdoor shooting range in California. The scientists assigned to the study found that “the only potentially effective noise control method to reduce students’ or instructors’ noise exposure from gunfire is through the use of noise suppressors that can be attached to the end of the gun barrel. However, some states do not permit civilians to use suppressors on firearms.”

Getting the Message Out

The CDC wrote their study the same year that we formed the American Suppressor Association. At the time, there were 285,000 legally obtained suppressors in circulation in the 39 states where they were legal to own. A mere 22 of these states allowed their use while hunting. In our minds, that wasn’t good enough.

Today, in large part because of our work, over 2,664,000 suppressors are owned by law-abiding citizens in the 42 states that now allow suppressor ownership. Hunters in 40 states are now allowed to use suppressors to help protect their hearing in the field.

The fact is suppressors should be used in conjunction with earplugs and earmuffs, not in lieu of. After all, suppressors don’t eliminate the noise; they reduce it to safer levels. The fact that a sound level equal to a jackhammer is somehow safer illustrates just how loud guns really are. We don’t tell people to stop wearing seatbelts if their car has airbags. The same principle applies to suppressors: the best way to protect your hearing is by using a suppressor while wearing traditional hearing protection devices.

This is why the National Hearing Conservation Association’s Task Force on Prevention of Noise-Induced Hearing Loss from Firearm Noise wrote in March, 2017 that “using firearms equipped with suppressors” is one of “several strategies [that] can be employed to reduce the risk of acquiring NIHL and associated tinnitus from firearm noise exposure.”

Now that you know the facts, it’s up to you to decide what you want to call them. Like Kleenex and Band-Aid, will you go the name brand route, calling them silencers because that’s what Maxim called them? Or are you the tissue and bandage type who will choose to call them suppressors? For us at ASA, it makes no difference what you choose, so long as you know that they are an effective tool to help mitigate hearing damage.

Knox Williams is the President and Executive Director of the American Suppressor Association.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V26N1 (January 2022) |