By Matthew Moss; Patent Graphics, The U.S. Patent Office

With the popularity of firearms suppressors at an all-time high and the Hearing Protection Act hopefully gaining momentum in Congress, it is an appropriate time to ask: When did suppressors first emerge and why did they disappear? At the turn of the 20th century there was an explosion of silencer designs and by 1912 the U.S. Army had become interested in their military applications, but the Great Depression and the 1934 National Firearms Act saw sales decline.

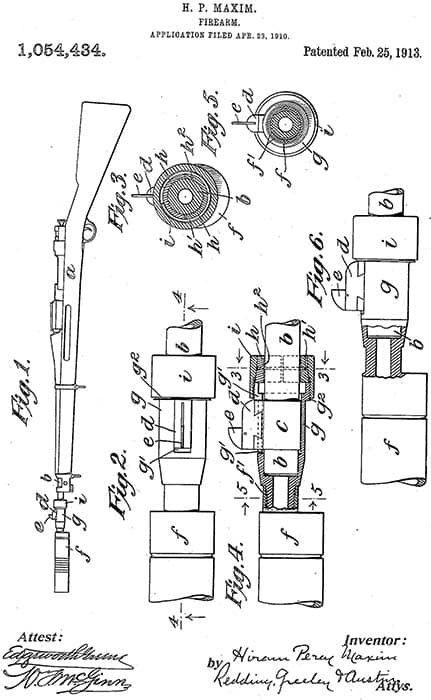

The first viable firearm suppressors appeared at the turn of the 20th century with a series of patents between 1909 and 1920. In 1895, Hiram Percy Maxim, son of Sir Hiram Maxim—inventor of the machine gun—established an engineering company. Initially, Maxim’s company was focused on the burgeoning automobile market. It was not until 1905 that Maxim began developing a series of designs to moderate sound. To begin with, he experimented with valves, vents and bypass devices. He eventually finalized his basic idea and developed a series of practical suppressors; these were sold by the Maxim Silent Firearms Company, which later became the Maxim Silencer Company.

In later years, Maxim claimed that he came up with the idea after taking a bath. As he watched the water drain out of the bath he noted that it spiralled as it formed a whirlpool at the drain. He believed that the propellant gases leaving a firearm’s muzzle could also be whirled to create a vortex, thereby slowing them sufficiently to prevent them making a noise as they left the muzzle.

Maxim experimented with his idea and created his first silencer, which used an offset chamber and valve to trap and swirl the muzzle gases in an effort to slow their travel. Maxim’s results with this design were encouraging, but the design needed further refinement.

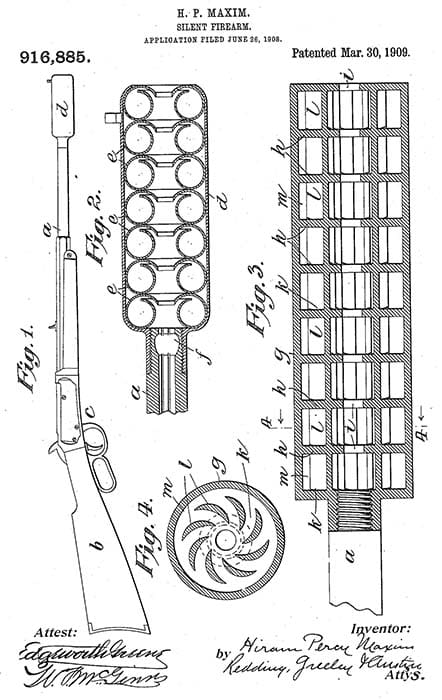

In June 1908, he filed his patent for an “improvement in Silent Firearms.” Granted in March 1909, this design used curved vanes or blades to create a series of miniature vortices to capture and slow the muzzle gases.

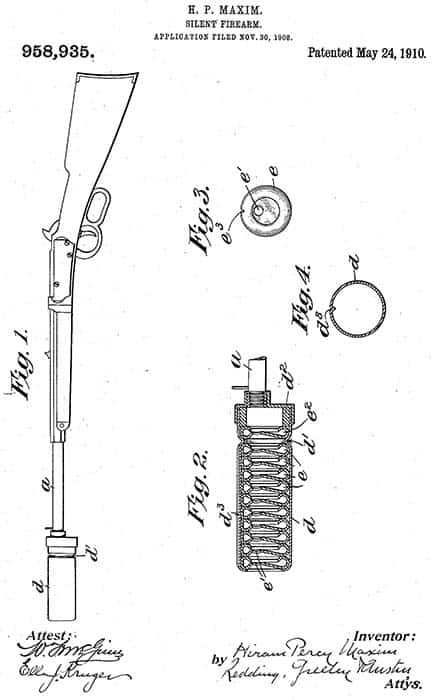

The Model 1909 Maxim silencer was not produced in great numbers and the vortices caused the suppressor to heat up rapidly. While the Model 1909 could reduce a .22LR pistol’s report by up to 30 decibels, the curved internal vanes proved expensive to manufacture. In October and November 1908, Maxim filed two more patents to protect an improvement on his earlier design. This new design became the Model 1910; it still relied on Maxim’s gas vortex theory but had a simplified vane arrangement. The Model 1910 also moved away from having a centrally aligned internal channel and instead used an offset or eccentric design. This had the added benefit of not obstructing the weapon’s sights.

The majority of rifles of the day did not have threaded barrels, so Maxim developed a coupling device that was placed over the muzzle and offered an external thread. One of the main drawbacks of the Model 1910 was that it could not be disassembled for cleaning. Instead Maxim sales brochures recommended that hot water should be run through the silencer’s channel for 30 minutes.

The Model 1910 proved commercially successful and was offered in a number of calibers from .22 up to .45 caliber. The thinner Model 1910 was less effective than the earlier 1909, but when fitted to a .22LR pistol the Model 1910 could still reduce the weapon’s report by up to 25 decibels. Both the 1909 and 1910 models proved to be fairly robust and moderately effective suppressors.

A second variant of the Model 1910 did not use the vortex-creating vanes, instead it used straight baffles (which the patent described as “spreaders”), as Maxim increasingly understood that the most important element of the suppressor was its ability to slow the movement of the muzzle gases.

Maxim’s book Experiences with the Maxim Silencer compiled letters from sportsmen and hunters who had used his silencer. In the book’s foreword, Maxim explained that he developed his system in order to “meet my personal desire to enjoy target practice without creating a disturbance. I have always loved to shoot, but I never thoroughly enjoyed it when I knew the noise was annoying other people.” This continues to be a key argument for suppressor usage today.

The Maxim Silencer Company sold the silencers via mail order, shipping them in cardboard tubes. A .22 caliber silencer cost $5 while larger-caliber silencers cost $7. Maxim’s silencers were expensive items; when adjusted for inflation, these prices respectively equate to approximately $120 and $165.

The adventurer president, Theodore Roosevelt, suppressed his .30-30 Winchester Model 1894 with a Maxim silencer. Roosevelt used his rifle for small game hunting on his Long Island property. Maxim’s commercial silencers sold well during the 1910s and 1920s with hunters, target shooters and plinkers all purchasing silencers. Maxim even sold indoor target backstop boxes that could be filled with sand and used in conjunction with a silencer to shoot indoors.

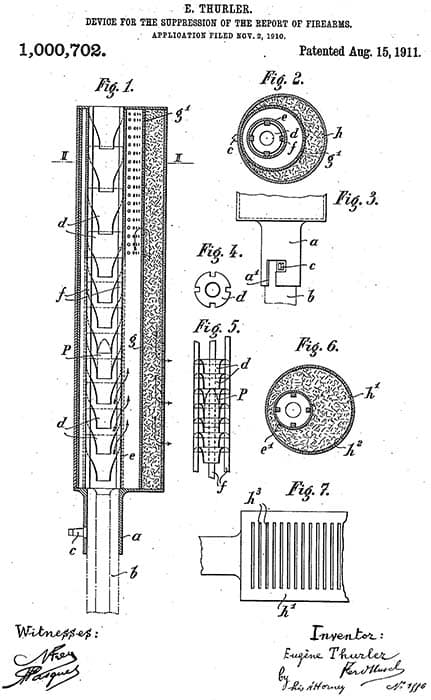

Maxim’s Rivals

With the success of Maxim’s silencers, a number of rival companies began selling their own designs. The early 1910s saw a flurry of designs patented, which included the following: James Stinson’s “Gun Muffler”; the George Childress hemispherical expansion chamber silencer; Charles H. Kenney’s 1910 silencer, which had a large pre-expansion chamber; and Andy Shipley’s 1910 patent was one of the first to suggest porting the firearm’s barrel. Others included Major Anthony Fiala’s spiral baffle silencer; Harry Craven’s early shotgun silencer; Eugene Thurler’s 1911 patent that described a bayonet-style attachment system and used deflecting cones; Herbert Moore’s gas trap; and R.M. Towson’s “Recoil Neutralizer and Muffler,” which was little more than an unconventional muzzle brake for both small arms and artillery.

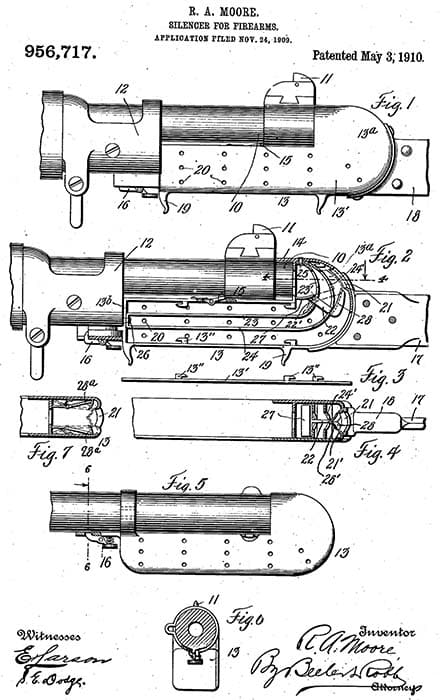

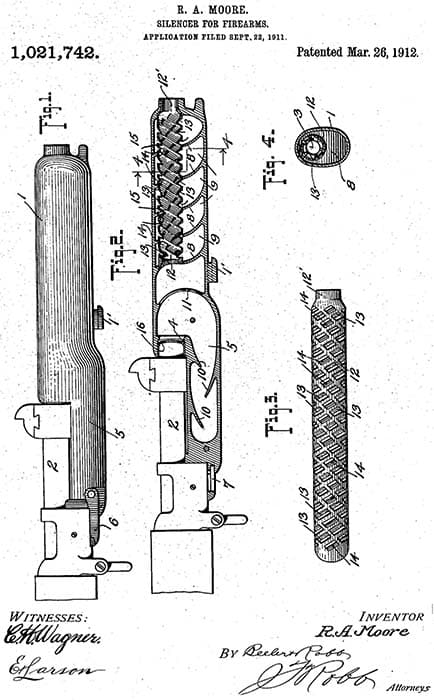

Among the multitude of rival designers, Maxim’s most competent competitor was Robert A. Moore, who patented his first silencer design in 1910. Developed for large caliber hunting and military rifles, Moore’s design included a large gas chamber that sat beneath the rifle’s muzzle. The muzzle gases were supposed to be deflected by concave surfaces down into the silencer, which had a number of partitioned chambers. The sides of the silencer were ported with vents to allow cool air to rush into the casing and, theoretically, cool the gases. The entrance to the silencer’s chambers also had a movable divider that was opened by the force of the gases and closed to prevent their escape.

Moore’s silencer had a number of interesting features. For instance, it used a rifle’s bayonet lug as an attachment point and also had removable side plates to allow cleaning of the silencer’s interior—both practical features for military use. Moore’s first design, however, did not go into production and he began work on a second model.

In 1912, Moore patented a more sophisticated silencer, moving away from the ported chamber concept. Instead, Moore’s new design first trapped the gases in a large expansion chamber, which again deflected some of the gases into a chamber beneath the muzzle. The silencer also had an additional series of curved baffles in front of the muzzle with expansion chambers below them. The elegant curves of the chamber partitions were designed, much like Maxim’s, to impart spin and create vortices to slow the travel of the gases. Moore’s patent explained that the curved baffles created two separate sets of vortices that slowed one another down when they intersected. The result was a silencer which attempted to slow the travel of gases with both expansion chambers and vortex-creating baffles.

Ingeniously, Moore designed his baffle system to be removable to facilitate cleaning and maintenance. Moore’s 1912 silencer also used the rifle’s bayonet lug as an attachment point and also provided another lug on the silencer’s housing to allow a soldier to attach a bayonet even while using the silencer. There were, however, some issues with fixing a bayonet while using the silencer. The additional length of the silencer combined with the bayonet meant the rifle’s balance was adversely affected, making it muzzle-heavy and difficult to fire accurately off-hand. During trials of the rifle it was noted by Ordnance Corps evaluating officers that the silencer’s rounded muzzle allowed the bayonet ring to slip under recoil.

The Military Maxim and the U.S. Silencer Trial

In 1912, with commercial growth slowing, Maxim turned his attention to the Military market and began designing a silencer that could moderate the report of a Springfield M1903. The Ordnance Corps had tested Maxim’s first silencer in 1909. Colonel S.E. Blunt, the commanding officer of the Springfield Armory, reported that the silencer eliminated approximately 66% of the noise and 67% of the recoil normally made when a rifle was fired.

The Maxim Silencer Company developed the Model 1912 and subsequently the improved Model 15, which Maxim christened the “Government Silencer.” Encouraged by the early military interest, Maxim envisioned a military silencer being useful in roles such as sniping, guard harassment and marksmanship training. He believed that the increasing number of inexperienced shooters from cities joining the U.S. military was struggling to master the .30-06 M1903 because of its loud report and recoil. Maxim felt that using a silencer would prevent recruits being intimidated by their rifle and help them to learn the fundamentals of marksmanship faster.

The U.S. Army decided to test both Moore’s and Maxim’s suppressors. When they compared the two rival designs, there was little difference between them with regard to the reduction of sound, recoil and flash. However, the Springfield Armory’s report in July 1912 found that the Moore silencer was more accurate and had a better attachment system. The Maxim silencer, on the other hand, was more durable and could withstand more prolonged rapid fire. Army Ordnance recommended the purchase of 100 of both silencers for field trials with two silencers to be issued per company for use by sharpshooters in conjunction with two star-gauge (accurate barreled) rifles and the M1908 and M1913 Musket Sights. This was not the large-scale contract that Maxim had hoped for, however, the funding was not available and the idea behind the silencers’ use was not fully embraced by the military.

The U.S. military’s first deployment of silencers came in 1916, when General John Pershing’s Mexican expedition against Pancho Villa included a squad of snipers apparently armed with silenced M1903s, however, little is known about their use in the field.

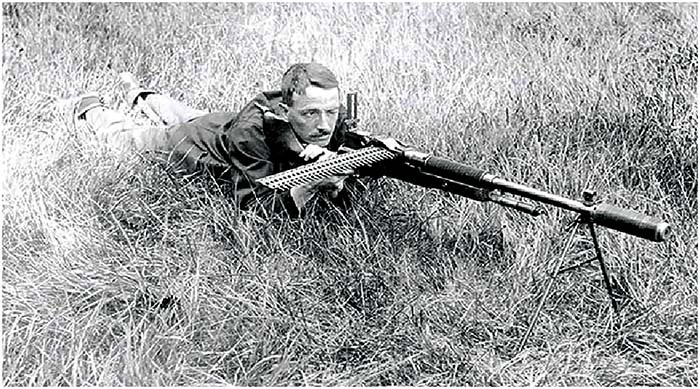

Maxim’s military silencers shipped around the world, with orders from Mexico, South America, China, Japan, Britain, France, Belgium, Russia and Germany. One pre-war Maxim advert boasted that the design had been approved by the German military. During the First World War, both the British and Germans deployed snipers equipped with Maxim silencers in small numbers. Some American troops deployed to Europe were also equipped with silencers, which were often paired with the M1913 Warner & Swasey “Musket Sight.” While these rifles could not prevent the supersonic crack that occurred downrange, they were able to mitigate muzzle flash and the rifle’s report. In 1917–18, a plan to deploy silencers with rifles with accurate star-gauged barrels was developed. An order for 9,100 was placed. Although part of this order was fulfilled before the end of the war, the exact number of silencer-equipped rifles manufactured remains unknown. After the war, these rifles were offered for sale through the Civilian Marksmanship programme in 1920, others were given to National Guard units for training purposes, and the remainder were declared obsolete in March 1925.

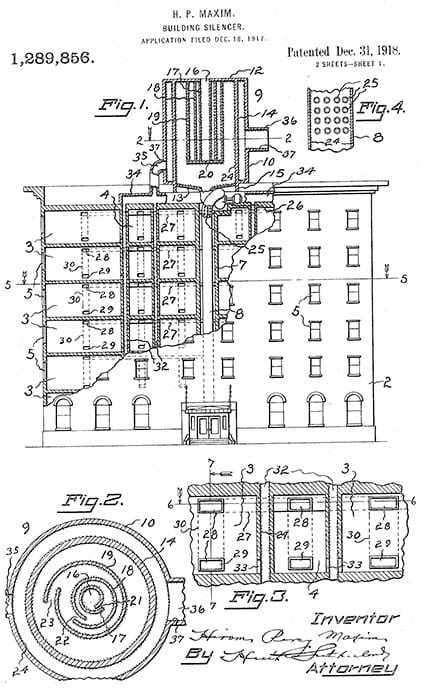

While the First World War offered a brief boom in sales of silencers this did not last, and Maxim’s company continued to diversify after the war. The Maxim Silencer Company manufactured not only firearm silencers but also sound-moderating devices for everything from automobiles to naval engines; from plant machinery to building silencers which were fitted to heating and air conditioning systems. Similarly, Moore, like Maxim, also later developed silencers for automobiles, filing a patent for an Exhaust Muffler in 1930.

The company began to move away from firearms silencers in 1925, instead concentrating on industrial and automotive sound moderators. Hiram Percy Maxim died in 1936, and his son took over the company. Although no longer family-owned, the company continues to specialize in industrial sound-moderating technology.

The National Firearms Act and the Decline in Civilian Silencers

The civilian market for firearms silencers was dealt a severe blow in 1934, when the National Firearms Act was introduced in response to the rise of organized and violent crime, with gangsters like John Dillinger and Baby Face Nelson increasingly using automatic weapons. While the use of silencers by gangsters was minimal, they were included in the National Firearms Act, which required a tax payment and registration of their ownership with (what later became) the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. While this was not a ban on suppressors, the prohibitively expensive $200.00 tax stamp (approximately $3,500 today) placed on them effectively killed the market. Interestingly, during the National Firearms Act’s passage through Congress, silencers were almost never mentioned during the debates or committee meetings. It is often said that they were included at the request of the Department of the Interior to prohibit poaching or as a personal preference of the Attorney General Homer S. Cummings; however, the true reason for their inclusion in the act remains unknown.

The result of the National Firearms Act was that all silencers had to be registered and that pre-existing unregistered silencers were subsequently illegal to own. This has led to the destruction of many early examples to avoid Federal penalties.

It was not until the outbreak of World War Two that silencer technology would be revisited by the military. The technology was not adopted for the training uses envisaged by Maxim, but for specialized, clandestine roles that required quiet, efficient and deadly weapons.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V21N7 (September 2017) |