By Michael Heidler

People often have crazy ideas. Combined with megalomania and arrogance, they then create things like bomb-carrying bats. This “lowest form of animal life” could have burned down Japan during World War II.

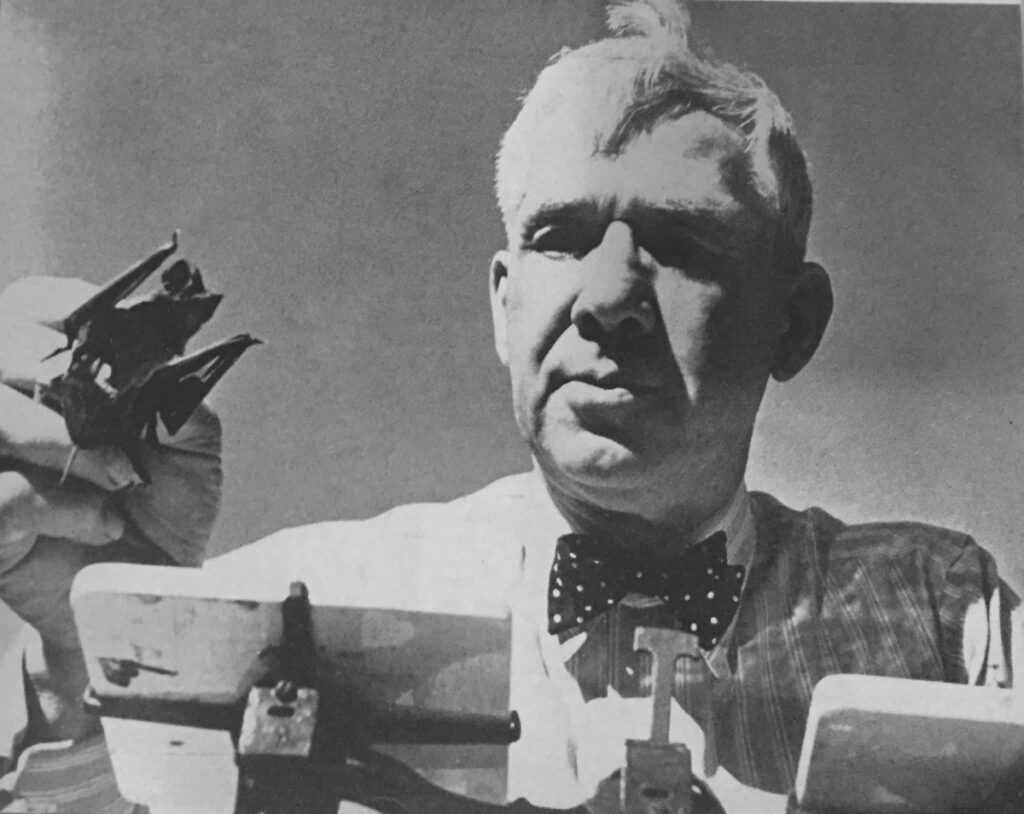

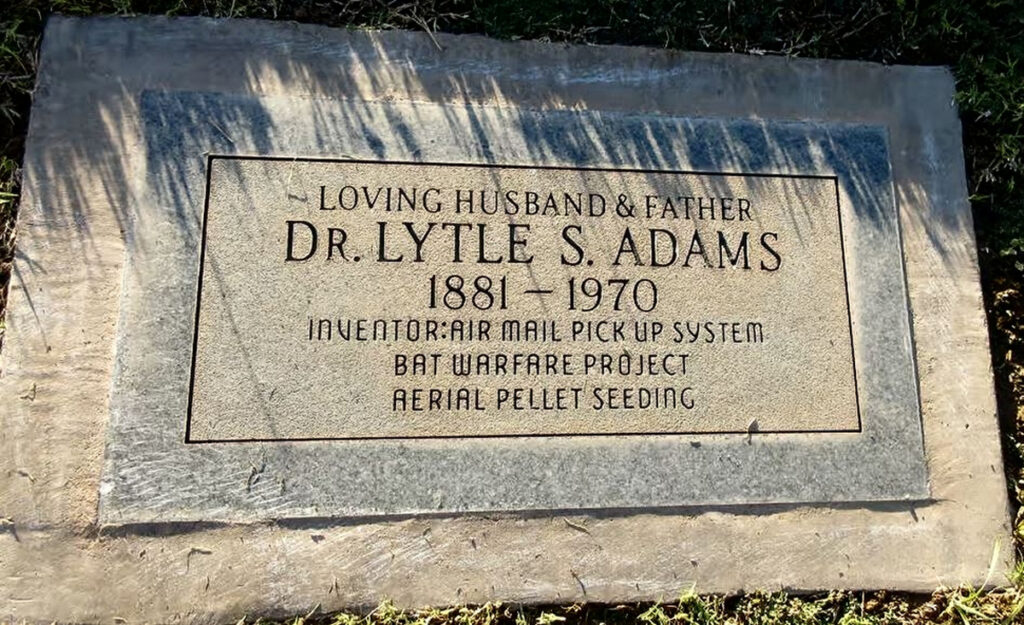

It all started with a holiday. Dr. Lytle Schuyler Adams, a dentist from Pennsylvania, spent a few weeks in New Mexico in December 1941. Among other things, he visited Carlsbad Caverns National Park with its famous stalactite caves. These were then, as now, home to around one million Brazilian free-tailed bats. Their evening fly out of the caves for hunting is an impressive natural spectacle and attracts tourists from all over the world.

On the drive home, Doctor Adams’ ideal world was dealt a severe blow, for he heard on the car radio about the attack on Pearl Harbor. The United States of America suddenly found itself at war with Japan. Doctor Adams was outraged. As a great patriot, various thoughts of retaliation were soon buzzing around in his head. And the countless bats he had observed on holiday came back to his mind. In view of the traditional construction of Japanese buildings made of bamboo, wood, and paper, he devised a most perfidious plan: bats equipped with incendiary material were to set Japan’s cities ablaze.

Since in Dr. Adam’s religious world of faith, man, as the highest living being on earth, may freely dispose of all animals, he also had no inhibitions about this matter. He put his idea on paper and sent a letter to the White House in Washington D.C. in January 1942. He was helped by his acquaintance with President Roosevelt’s wife Anna Eleanor. In his letter, Dr. Adams stated that the bat was the “lowest form of animal life” and that “reasons for its creation have remained unexplained“. Completely insane, he went on to write that bats were created by God to wait to play their part in the plan of free human existence and to thwart any attempt by those who dare to desecrate that way of life. Roosevelt read the letter and noted “This man is not a nut“. It sounded like a crazy idea to him, but it would be worth looking into.

Dr. Adams gave four reasons why the bat was the ideal object: They are strong enough to carry a small load. By lowering the temperature, they go into hibernation, which makes it easier to load and transport them. In daylight, they seek dark hiding places, such as cellars and attics. And finally: there are millions of bats, so there is an almost infinite supply.

After Roosevelt gave his approval to the project, it became the responsibility of the U.S. Army Air Force. Adams assembled the staff for the project, including mammologist Jack von Bloeker, who described himself as a “bat lover”. In a later interview, he admitted that it never occurred to him to question the morality or ecological consequences of sacrificing a few million bats. Actor Tim Holt was also part of the team, then still 23 years young and at the beginning of his career as a western actor.

First of all, the type of bat had to be determined. After testing several species, the choice fell on the Brazilian free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis). Dr Adams had to ask the National Park Administration for permission to take a large number of these animals from the caves on government land.

The original plan was to equip the bats with white phosphorus. But then the chemist Louis Frederick Fieser joined the team. At the time, he was experimenting with a sticky, slow-burning incendiary compound that would later become famous: Napalm.

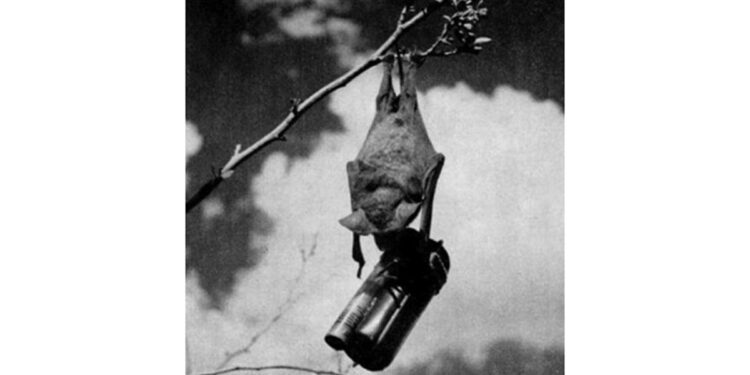

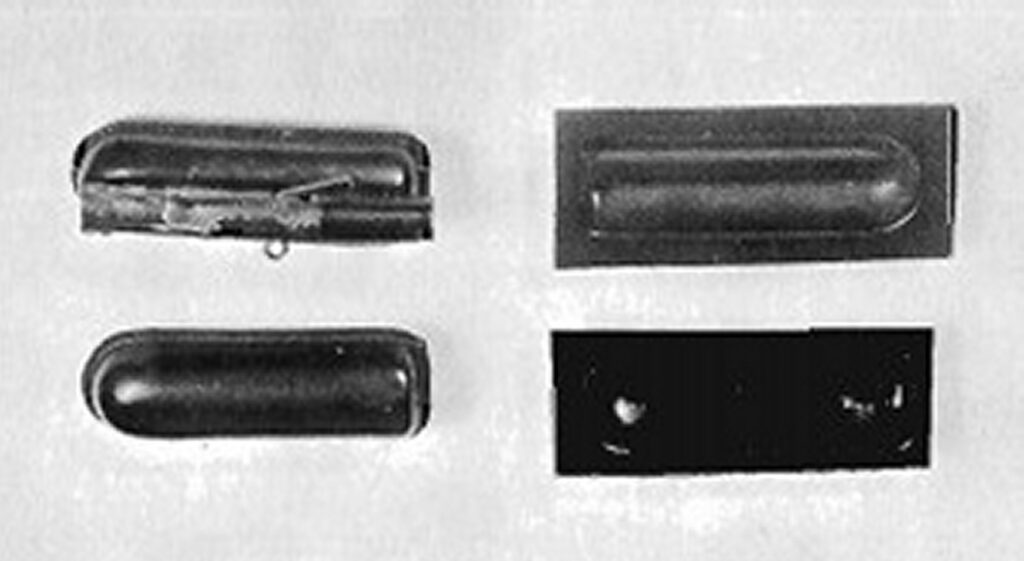

In tests, a 0.5 oz. (14g) bat could carry about 0.53 – 0.63 oz. (15 – 18g) of payload. The napalm was filled into small, easily inflammable cellulose containers, so-called “H-2 Units.” After trying different methods of attachment, it was decided to stick the containers to the bats’ chests with a strong adhesive. This method would also be quick, given the large number of animals to be prepared.

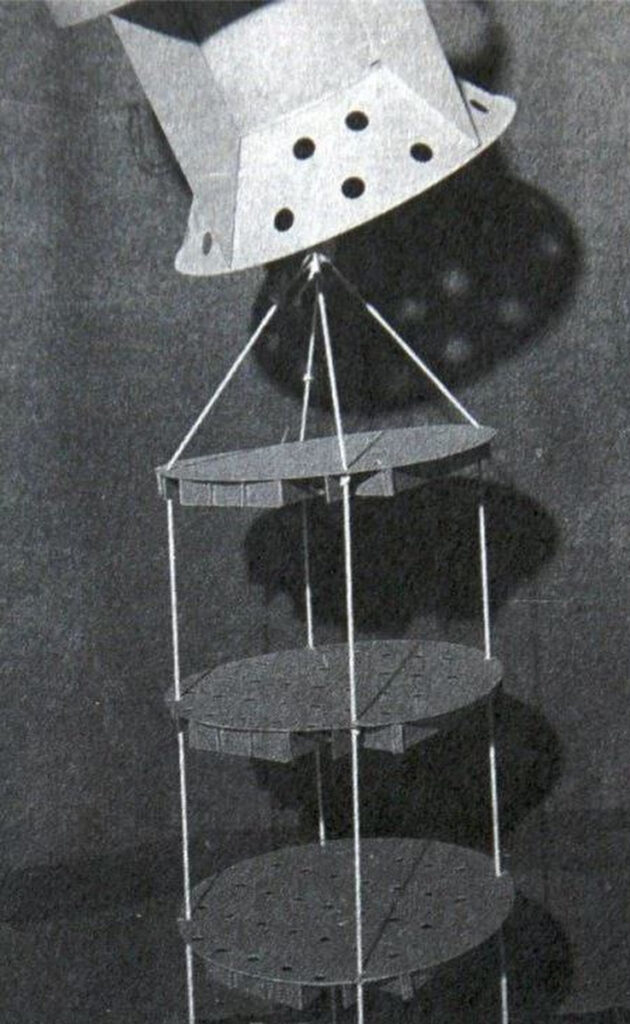

Now the flying incendiaries had to be brought to their destination. Dr Adams had a new employee named Andrew Paul Stanley make a cardboard model of a drop container. Inside were 26 round trays, each 76cm in diameter, each stacked on top of the other with a spacer. The trays were stacked with the open side down and connected at the edges with 7cm long strings. On the parachute, the trays would then hang among each other like an accordion. Each tray would hold 40 bats in individual chambers, similar to a square egg box. This means a total of 1,040 bats per transport container.

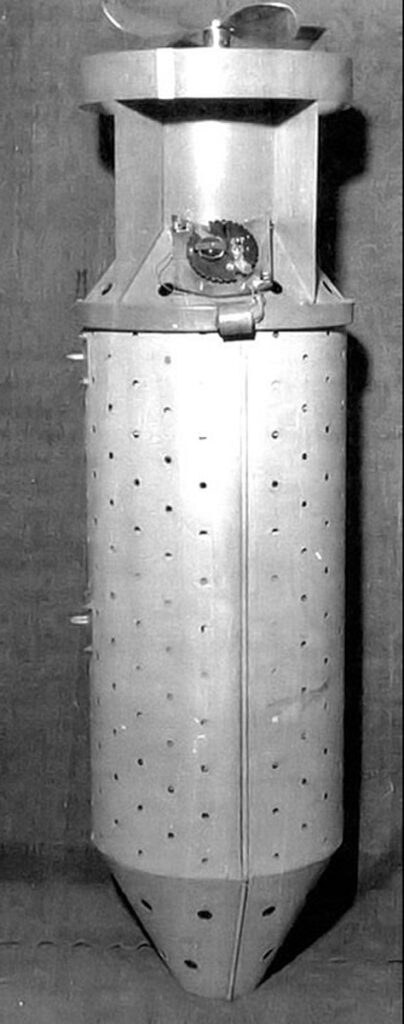

During the first test flight, the (still empty) cardboard container was shredded by the air current. So they turned to a small engineering firm in Del Mar, which belonged to the singer and actor Bing Crosby and his brother Larry. There, based on the plans of the cardboard model, a version in sheet metal was designed. Only the trays for the bats remained made of cardboard. The 5 ft. (1.5m) long transport container was also fitted with a parachute for slower sinking, a barometric opening device for dropping the side parts and a small heater to wake the bats from hibernation before dropping.

It was then to be brought to Japan by plane. After being dropped at dawn, at an altitude of 4,000ft (1,200m), the brake parachute would release, and the sides of the container would fall off. The bats would then be free to make their way to a protected shelter within about 20 to 40 miles (32 to 64 km).

Dr Adams was thrilled and ecstatically wrote down his ideas: “Think of thousands of fires breaking out simultaneously over a circle of forty miles [64 km] in diameter for every bomb dropped. Japan could have been devastated, yet with small loss of life“.

But the time had not yet come, and the bats first wreaked havoc in America itself. Due to carelessness, some animals equipped with incendiary devices escaped from the Carlsbad Army Airfield Auxiliary Air Base on 15 May 1943 and hid in hard-to-reach corners, such as under the tanks with the fuel supplies. And the ‘weapon’ worked – the large fire that was set off destroyed numerous buildings and there were several casualties.

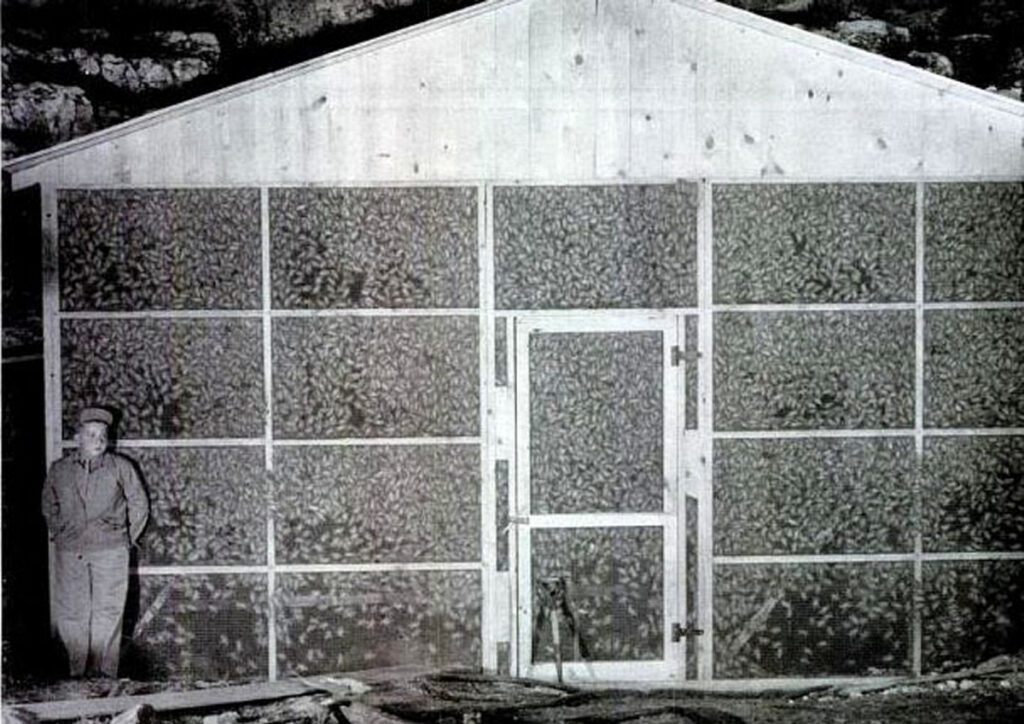

After this embarrassing setback, the project was transferred to the Navy in August 1943, which renamed it ‘Project X-Ray’. Then in December, the Marine Corps took over the project and moved test operations to the Marine Corps Air Station at El Centro in California. After several trials and operational adjustments, the final test was conducted with the Japanese Village. This was a replica of some Japanese houses in typical construction, which had been built by the Chemical Warfare Service on the test site Dugway Proving Grounds in Utah. Right next to it, by the way, there was also a German Village, with two more sturdily built row houses made of bricks and concrete.

The results report provides interesting insights: “A reasonable number of destructive fires can be started in spite of the extremely small size of the units. The main advantage of the units would seem to be their placement within the enemy structures without the knowledge of the householder or fire watchers, thus allowing the fire to establish itself before being discovered“. The National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) observer noted that X-Ray was an effective weapon and was more effective on a weight basis than the standard incendiary bombs of the time: “The normal bombs would probably cause 167 to 400 fires per bomb load, while X-Ray would cause 3,625 to 4,748 fires“.

Further tests were planned for summer 1944, but then the program was cancelled by Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King. By this time, an estimated 2 million U.S. dollars (equivalent to 18.7 million U.S. dollars today) had been spent on the bat project. Presumably, progress was too slow for him, because in the meantime another weapons development had progressed very promisingly: the atomic bomb.

Photos: Dugway Proving Ground Archive, Aberdeen Proving Ground Ordnance Museum