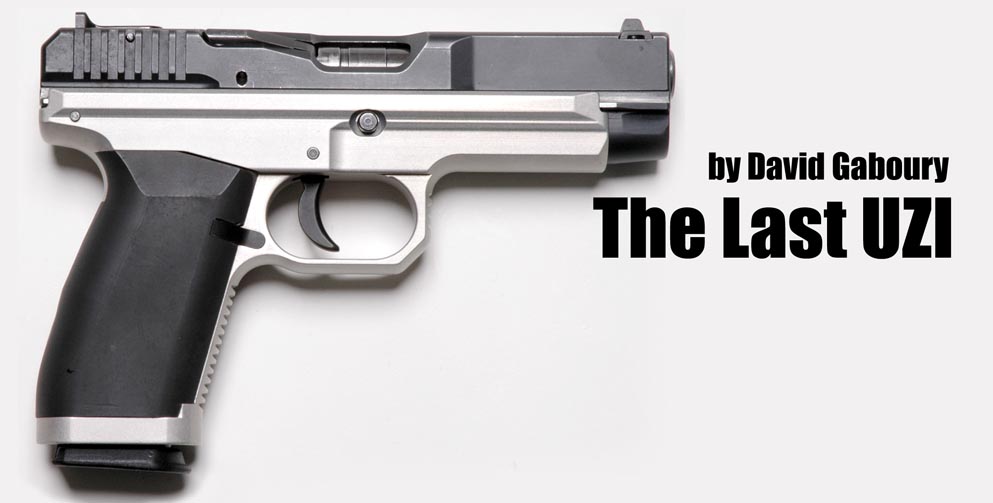

Uzi Gal named his pistol the Model 101. All of his prototypes used a standardized numbering system that identified the type of weapon and caliber.

By David Gaboury

Anyone who knows the name Uzi Gal recognizes him as the designer of the UZI submachine gun. Many people also know he designed the semiautomatic UZI carbine that was sold in the United States by Action Arms from 1980 until 1989. But those are just two projects from a lifetime devoted to firearms design. During the 25 years he lived in the United States, Gal did consulting work for many firearms manufacturers, including Colt, Ruger and Knights Armament. His final design project was a semiautomatic pistol and he worked on it until illness forced him to stop shortly before he died.

Uzi Gal moved to the United States in 1976 and began working under contract for Action Manufacturing. He set up his own business called Gal-Tech and obtained an FFL and SOT. During the 1980s and early 1990s, Gal was extremely interested in the new crop of semiautomatic pistols appearing on the market. An examination of his FFL logbook shows that he purchased many 9mm and .40 S&W pistols. He examined those guns carefully; weighing, measuring and analyzing each of the gun’s components. Ergonomics and reliability were paramount to Gal and he felt that no one had achieved the perfect combination. The solution to this problem was to design a pistol himself. His goal was not to come up with a revolutionary new design but to put together incremental improvements across several key design areas. He believed that by meticulously inspecting the strengths and weaknesses of the many pistols on the market and applying his own insights learned through years of design and combat experience, he could design a weapon that was friendlier to the casual as well as the professional shooter. Gal believed that soldiers could use a poorly designed gun after extensive training, but an infrequently used self-defense pistol must have an optimal design to keep the casual shooter from fumbling with it. That was the pistol he wanted to design. While such a pistol would be ideal for the civilian market, Gal also knew it would give an edge to law enforcement and military users and he hoped for widespread use of the weapon.

By 1997, Gal had a Technical Data Package (TDP) assembled for his new pistol and he engaged a group of investors to fund his project. Initially the investors created an Israeli based company with the intention of manufacturing the pistol in Israel and exporting it to the U.S. and other parts of the world. It was hoped that IMI could be contracted do the manufacturing of the pistol and negotiations went on for a time, but IMI eventually turned down the project. They were already working on a new pistol that eventually became the Jericho (Baby Eagle). Gal considered working with Diemaco, the Canadian company he worked with on his model 201 submachine gun (which became the Ruger MP9), but he wanted to avoid the inherent problems of shipping prototype pistols back and forth across the border. Finally, Gal and the investors reached a deal with Reed Knight at Knight’s Armament Company (KAC) to use their facilities to build the pistol prototypes and work on the pistol could now begin.

Technical Details

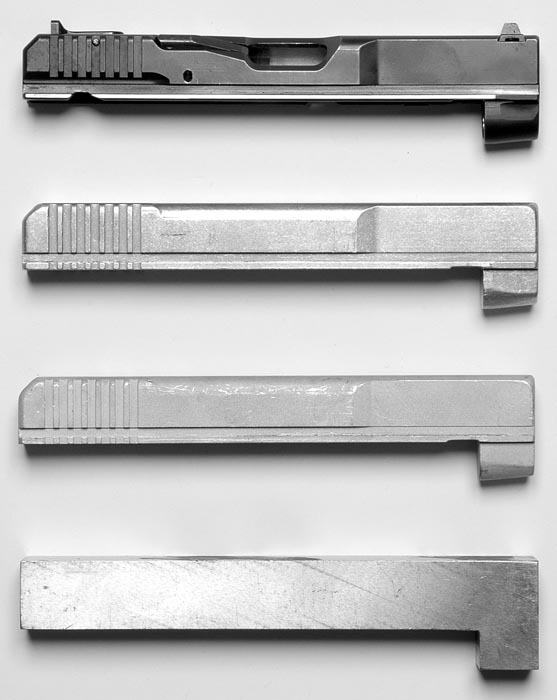

Uzi Gal’s design was for a mid-sized 9mm pistol built on a machined aluminum frame. He planned to make a polymer frame at some point but not until the aluminum framed pistol was complete and on the market. Much of his design focused on the features Gal thought were essential to reliable use in real-life defensive situations; including the placement of all control levers, the ergonomics of the grips and the overall reliability of the pistol. Most of the major parts for the prototypes were made at KAC, while small parts such as pins, buffers, springs and screws were purchased from standard U.S. suppliers. Two components required external vendors: the slide and the barrel. The machined steel slide was rough formed by one of the vendors, finished machined by KAC, and then heat treated and nitrided by another vendor. On the prototypes, the heat treat and nitriding stress relieved the heavily machined slide and caused it to warp. The problem would have to be resolved on production guns.

The barrel, designed by Gal, was produced by Lothar Walther and was the heart of the pistol. It contained both the locking lugs, which locked the barrel to the slide, and the cam lug. The cam lug ran in a separate piece under the barrel called the cam pathway, which caused the barrel to rotate and separate from the slide. Gal was very protective of these features, and vendors were never provided any information about the lugs that would allow them to understand how the pistol worked. Lothar Walther was provided a different print of the barrel that had extra material where the locking lugs and cam lug would later be machined out at KAC. Both 1:10 and 1:16 twist barrels were tried in the prototype and while both were accurate; the 1:16 twist gave the best performance across nearly all types of 9mm ammunition.

The pistol used standard SIG P226 magazines. Gal knew that careful design, extensive testing and stringent quality controls are needed to produce a successful magazine and the process can easily stall the design effort for a new weapon. Additionally, this choice would provide a source of high-capacity magazines during the assault weapons ban.

Working with a Legend

This author recently had a chance to interview Trent Warncke of Inverse Technologies. For almost a year he was a design engineer at KAC and served as the program manager on Gal’s pistol project. Warncke’s experience on that project gives interesting insight into the thinking of a legendary firearms designer.

SAR: At what point did you get involved with Uzi’s pistol project?

Warncke: I started working at Knight’s Armament in April 2001 and a few weeks later started working with Uzi on the project. My role was a mix of design engineering and program management. I coordinated work with subcontractors to ensure that the pistol parts were made to Uzi’s liking and assisted Uzi with design, testing and eventually financial oversight for the program. When I took the program over it was relatively mature. The first prototype was complete and had successfully fired at least 100 rounds. The goal was then to get a second prototype built and start debugging it. Uzi traveled to KAC two weeks a month and while he was back in Philadelphia, I did a lot of the legwork to keep the project moving. KAC was to make a total of 12 prototypes. Only two complete prototypes were made to my knowledge, as Uzi’s death shut down the program.

SAR: What design criteria were most important to Uzi?

Warncke: Reliability was almost everything to him. He saw the need firsthand in the IDF and knew that simplicity of design was an essential part of reliability. His baseline for the pistol was influenced by the early 1980s test reports of the U.S. Military’s sidearm, which yielded the Beretta 92FS and a Department of Justice test plan that called for no more than one malfunction per 2,000 rounds. Uzi would not be happy until the pistol met that DOJ specification. He also referred to various testing procedures that many different weapon manufacturers and militaries used to test reliability. Uzi said he wanted to subject the pistol to various mud and salt conditions, but we never got there.

Uzi also put a lot of emphasis on ergonomics. We spent hours in the extensive KAC museum holding various weapons and commenting on their ergonomics. The Colt 2000 was one of his favorite pistols in terms of good ergonomics.

SAR: So the KAC museum turned out to be a valuable resource in the design process?

Warncke: It definitely was. Uzi tried to learn from what other firearm designers had done. This may sound like an obvious approach but I know some designers who avoid examining other weapons so they don’t stifle their creativity. Uzi would often times ask me to accompany him to the KAC museum in order to examine several firearms. The pistol prototype didn’t have a safety yet and one would have to be added before it could be sold to in the U.S. We would hold pistols in the museum and talk about the safety location and ergonomics in order to determine where the safety should be located. He would spend a lot of time examining grips as well, being obsessive about their shape and texture. Uzi’s attention was mostly focused on issues that surfaced during testing of the pistol. When you fire several hundred rounds a day, many issues become apparent.

SAR: I can picture Uzi as an old-time craftsman building this gun by hand at a small workbench, but that’s not how he worked, was it?

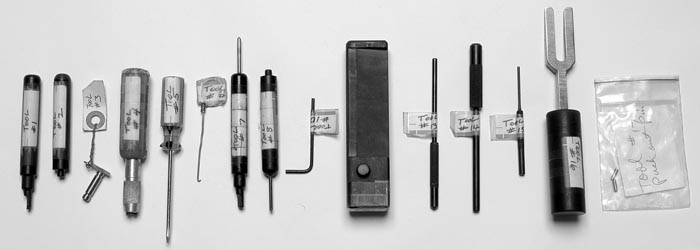

Warncke: No, not at all. Uzi didn’t make any parts himself, and he was very particular about that. He felt that to evaluate his design you must assemble and test weapons using parts that matched his prints. He felt that if he filed or Dremeled parts to make them work he would not have a good baseline, and the results would be inconclusive. Uzi had some 2-D CAD software that he ran on an Apple laptop. It would have been easier if he used our 3-D software from Solid Edge, but he was very concerned about electronic files being stolen so he only gave us printed copies of the TDS. A few parts with cammed surfaces were hard to call out on his 2-D software so I recreated them in Solid Edge. It became a challenge to keep the prints updated with all the revisions that many of the parts were going through as designs changed, but Uzi wouldn’t budge on the security issue.

SAR: What was the biggest design challenge you worked on with Uzi?

Warncke: We had a problem where the weapon would sometimes fail to extract the spent casing, causing a double feed. This malfunction rarely happened but it was very concerning to Uzi and he would not approve the pistol until this issue was resolved. The pistol used a rotating barrel principal in order to unlock the system. Our first thought was that the rotation of the barrel was “throwing” the extractor away from the centerline of the bore and thus causing the extractor to disengage or override the rim of the spent case being extracted. High-speed digital video yielded little help, but we were able to capture a malfunction with it. We tried stronger extractor springs to overcome whatever force was pushing the extractor out of engagement with the spent case’s rim. This seemed to help, but it was difficult to determine if the changes were sufficient since the malfunction only occurred a few times per thousand rounds of firing. We also tried reducing the mass of the extractor. Finally, we theorized that at the moment of firing, gases leaking before the case was fully expanded to the chamber walls may be forcing the extractor outward. To address this issue Uzi added gas relief slots to the extractor. All these solutions seemed to help the issue.

SAR: How did you handle the warping problem with the slides?

Warncke: The warping was very minor for most of the slides and was overcome by working the barrel in the slide. One solution that Uzi and I discussed was that production slides could be pre-heat treated, then machined with periodic stress relieving operations and lastly nitrided. This process would allow the oversized part to warp before the machining steps took place. The problem was that it would cost a lot more to machine the slide in the hardened state compared to the non-heat treated state so Uzi eliminated this option. The other option is to machine the slide from unhardened steel with periodic stress reliefs between machining operations. Once all the machining was complete, the entire part would be hardened or heat treated. The periodic stress relieving should prevent most warping during the final heat treat.

SAR: What was Uzi’s approach to solving problems?

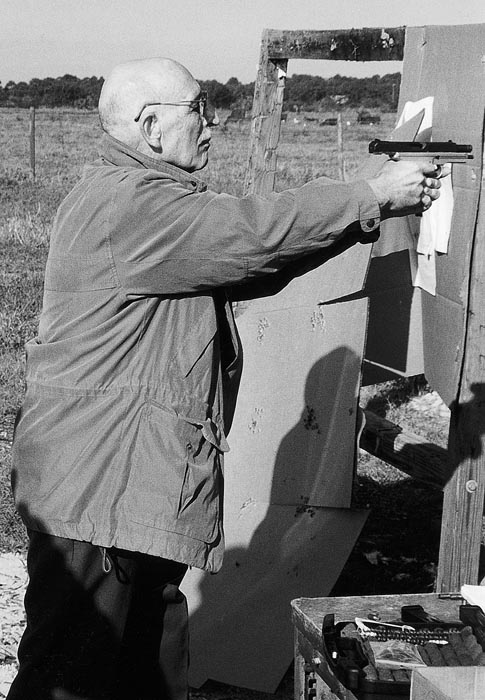

Warncke: His approach to problem solving was based on his work in the IDF where he spent most of his time doing small-arms research in both garrison and combat environments. He told many stories of testing new sights and various magazines in combat, keeping detailed records of how the stressed soldiers performed with the item being tested. His scientific approach of collecting field data was evident when we would live-fire the pistol and encounter malfunctions. Once a malfunction occurred, he insisted that I not move or clear the weapon. While holding the weapon pointed downrange, Uzi and I would analyze the malfunction and describe it in a logbook. All the magazines we used for testing were numbered and recorded with each malfunction.

As rigid as Uzi was about certain items such as collection of test data, he also possessed a “let’s try it” attitude. We tried a number of extractor designs to cure the extractor problem. One would think Uzi’s personality would have demanded a computer analysis of each of the new extractor designs, but instead he just had them made and we would go shoot them to determine the results. Uzi also asked others around him for advice when issues arose. He turned to Reed Knight many times for suggestions as Reed had designed the Colt 2000 Pistol with Eugene Stoner, and had dealt with issues that come along with a rotating barrel pistol. Uzi had strong opinions and would let you know if he disagreed, but he would listen to everyone’s opinion before making an important decision.

SAR: Did Uzi help with the marketing of the weapon?

Warncke: Uzi was a designer at heart, but he did help with marketing. Uzi and the investors knew it would be easy to find a manufacturer but it appeared they wanted to sell the TDP outright. Reed Knight suggested to Uzi that he talk to Bob Morrison of Taurus. Their U.S. headquarters was just south of KAC in Miami. On the first trip, we took one of the prototype pistols and met with Bob and one of Taurus’ top designers from Brazil. Overall, they were happy with the design. Uzi and I made a second trip to Taurus where we were able to meet with other officials of the company in hopes of them buying the TDP. Uzi’s son came with us to help his father due to his failing health. In the end, Taurus decided not to buy the design. I think they were afraid to buy the TDP when they knew Uzi would not be alive to help them with initial production problems, as is common with all new weapons. At this point, the project investors own the design and the prototypes. Maybe someday it will go into production or they might consider doing a limited production run of the guns for collectors who want to own “the last Uzi design.”

SAR: You must feel very fortunate to have had the opportunity to work with such a legend in the history of firearms.

Warncke: Uzi was truly one of the most influential people I have ever worked with – both as a small arms designer and as a person. I was fortunate enough to train under him for a year, but I was blessed to have been his friend. He possessed tremendous knowledge of small arms and his days of serving in the IDF taught him a lot of interesting things. He was always making comments that were in contrast to current opinions and he could back up his claims with actual combat test data from IDF soldiers. Besides having tremendous knowledge about small arms, Uzi was always patient and respectful with everyone. There were many challenges in the pistol program that would have made many people lose their temper. Uzi never once lost his temper or raised his voice. Even when he was disappointed by people, he had an attitude that would always make the best of a bad situation. He was also compassionate for all people. When he was telling war stories, it was clear that he respected the enemy as human beings. It was a real honor to work with Uzi on his last project, and I will never forget the time I spent with him.

Resources:

UZI Talk Discussion forums

www.uzitalk.com

Inverse Technologies

726 East Main Street

Suite F #161

Lebanon, OH 45036

(937) 470-7466

info@inverse-tech.com

Knight’s Armament Company

(321) 607-9900

www.knightarmco.com

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V11N9 (June 2008) |