by J. David Truby

Tough, disciplined Japanese troops hit the Philippines just after the Pearl Harbor attack, roaring through the islands, capturing Manila by January 2, less than three weeks later. The dazed American and Philippine survivors stumbled to Corregidor in retreat.

“With the Japanese in charge so quickly and firmly, the allies had only one hope to regain freedom – guerrilla warfare,” the British military historian Trevor Dupuy wrote of the deadly defeat.

Only days after the Japanese victory, word got around the islands that a few Americans were in the rugged mountains, trying to organize guerrilla bands. However, when Corregidor fell in May of 1942, the last headquarters of the Americans was gone. General Jonathon Wainwright, under great duress, ordered that all Americans surrender to the Japanese.

Not all Americans obeyed that order. Many chose to continue that battle. The true stories of many of these heroes, e.g., Blackburn, Noble and Moses have filled novels and have been the subject of films and military histories. Interestingly, one of their major universal problems was a severe shortage of firearms. Guns, badly needed to fight the Japanese, were a rare item, until a bright, young U.S. Navy officer showed up to help. Under the leadership of Lt. Iliff Richardson, USNR, the early Philippines guerrilla troops literally ripped apart their own plumbing and built guns to fight the Japanese, beginning on Leyte. Freedom’s revolution spread.

“Like a character in the book A CONNECTICUT YANKEE IN KING ARTHUR’S COURT, Lt. Richardson showed the guerrillas how to fashion the badly needed guns right in their own villages using scrap material like plumbing pipe and old lumber,” correspondent Ben Waters reported in 1944.

Young Richardson’s impact and fame were the right stuff for democracy, and his exploits were featured in two best selling books and Hollywood films of the ’40s. That’s the rare and right stuff for a preacher’s (dad) and a teacher’s (mom) son born in Denver in 1918, to accomplish in such a short time.

A rangy, 23 year old Ensign, with blond hair, Iliff Richardson evaded the Japanese during those first hectic war days of December, 1941, eventually fleeing into the hills with a few Filipino soldiers and other civilian refugees. The war correspondent Ira Wolfert wrote of Richardson’s experiences, “His life leading irregulars against the Japanese was a how-to book, e.g., how to make fuel for your car out of palm tree sap, or how to scrape your way through jail bars with a beer can opener, or how to make field artillery out of a brass pipe, how to tell time in the jungle at night when you don’t have a watch, or how to sail a banca, or how to make bullets out of a curtain rod.”

In 1938, Iliff Richardson was a young college student at California’s Compton College when he decided that we wanted to see the world before graduating. So, he spent 18 months traveling in Europe and the near and far East. He quickly surmised that a World War was in the immediate offering. He returned to the States just prior to the Fall of France in 1940 and enlisted in the U.S. Navy.

Because of his college background, after Boot Camp, he got into OCS at Northwestern University, graduated college, was commissioned, and by the fall of that year was on a minesweeper in the Philippines. He transferred to the new Motor Torpedo Boats in 1941, and volunteered for Lt John D. Bulkley’s PT Squadron 3, the so-called “expendables” that both carried General Douglas MacArthur’s family and staff from the Philippines to Australia, plus covered for that White House-ordered deployment. He served aboard PT Boats 33 and 34, and was at the helm of the 34 boat for the start of the MacArthur’s evacuation.

“After that, our mission was to run murderously outnumbered combat patrols around Bataan, Cebu, Corregidor and Mindanao against Jap transports, barges and gunboats, trying to keep the Japs busy while the brass got out,” Richardson said. “The Japs sunk most of us ‘expendables’ including my boat in Subic Bay.”

Richardson and other survivors managed to float wreckage and swim for nearly 24 hours, evading the Japanese, finally making land in Mindanao. Their plan was to steal a Japanese boat and reach Australia, 1300 miles away. Lt. (jg) Richardson took charge of ten stranded army air corps pilots and they tried to sail a native boat out for Australia. It was sunk, so he then led a 13-mile survival swim to Leyte. Again, they thought to get another boat to escape by sea.

Instead, Richardson and the others spent the next three years on Leyte, serving as guerrilla leaders eventually becoming chief of staff to Col. Ruperto Kangleon, the major resistance leader. Richardson set up and maintained the radio net that linked about 50 guerrilla groups, enabling them to coordinate their activities and to communicate with MacArthur’s headquarters.

In addition to the communications job, Lt. Richardson also became the officer in charge of ordnance, communications, finance, quartermaster, and public relations for Col. Kangleon.

During Richardson’s service on Leyte, MacArthur direct commissioned him as a Major in the US Army and appointed him as Army Intelligence liaison. He was also commissioned as a Major in the Philippine Army. This assignment meant he had to delegate his other duties while he concentrated primarily on communication and liaison between the guerrilla command and MacArthur’s people. Indeed, one of the first Americans MacArthur requested to see as the invasion of Leyte was taking underway was Major/Lt. Iliff D. Richardson. MacArthur personally awarded Lt. Richardson, USN, the Army’s Silver Star with oak leaf cluster, in lieu of a second Silver Star, was awarded two Presidential citations, plus there was talk of MacArthur nominating him for a Medal of Honor, which Richardson, in his own modest style, downplayed.

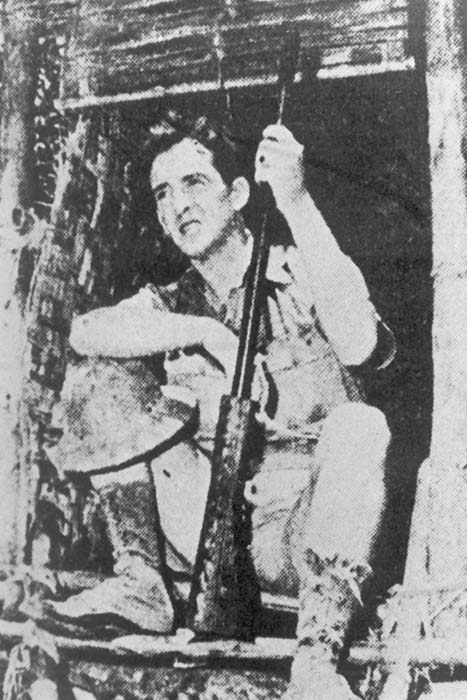

In addition to his leadership for three years, plus his ordnance skills, battle savvy and courage throughout the war, Iliff Richardson also made his own unique small arms contribution, the ubiquitous Philippine Pipe Shotgun. His 1942 “invention” shows up among armed rebels even today as various Philippine rebel groups continue to fight their various political battles, more than 60 years later.

“It’s a slam-action shotgun made from two pieces of plumbing pipe, a chunk of wood, and a nail. We made them from scraps,” Lt. Richardson explained in 1945.

“Sure, it’s crude and ugly. But it kills just as dead as that fine, expensive M1 rifle you have,” he replied to a skeptic who poo-poo’d the junk gun.

“The idea was to use our pipe shotgun to kill a Jap so our people could liberate one of their real rifles and all the other battle gear we could,” Lt. Richardson explained.

His shotgun was a rough hunk of wood, perhaps a whittled piece of old 2×4 with a hole bored in one end to accept a short bit of plumbing pipe. This was the crude receiver.

A nail was placed at the back of the receiver, sticking forward. Then a homemade, 12 gauge shotgun shell was loaded carefully into the longer, smaller diametered piece of plumbing pipe – the barrel.

Lt. Richardson said, “The two pieces of the gun were joined gingerly together when one of our men got close to action. Firing was a matter of clamping the wooden piece under your arm, then slamming that barrel back into the receiver, like a trombone. Hopefully, the sharp end of the nail hit the primer in the shotgun shell.

“If so, BLLOOOMM…the Emperor lost another soldier and our guys gained another real rifle and ammo from the departed Jap.”

The purpose of the Richardson pipe shotgun was not to engage the Japanese regulars in set piece, pitched battles. Rather, it was a “home-expedient weapon”, as the U.S. military quaintly called it in post war reports, “designed solely to kill enemy soldiers so that irregulars could acquire military rifles and ammunition.”

Later, the U.S. would furnish real military small arms to the guerrilla groups. But in the early days, they used Richardson’s pipe shotguns to harvest Japanese Arisaka rifles and ammunition. The process worked well.

Richardson led his guerrillas and their Rube Goldberg shotguns into many small group ambushes, early in 1942, explaining, “These pipe guns weren’t worth much in open combat, but they’re great for ambush. As soon as he got a modern rifle from a dead Jap, our man would pass his slam-bang shotgun on down the line to a new recruit, who’d pass it along after he used it to get his new rifle.”

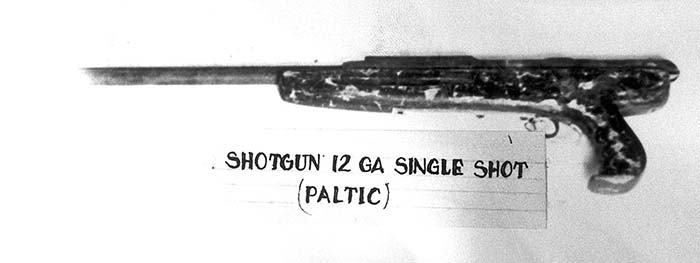

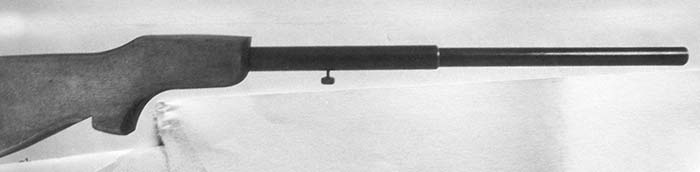

After the war, Iliff Richardson tried to market a commercial version of his weapon back in the States. He called it the M4 Guerrilla Shotgun, advertised it for “lowest cost hunting,” and sold it for $7.20. His slam-fire design took on a more commercial look as The Guerrilla Gun, Model R-5 12 gauge, which was manufactured by Richardson Industries, Inc of New Haven, CT. The gun was 36½ inches overall, with a 24-inch barrel, and sold for $7.99. Very few were sold and the idea was folded in 1947.

Literary history was kinder to Richardson, though. He was the inspiration for the war correspondent Ira Wolfert’s 1945 best-seller, AMERICAN GUERRILLA IN THE PHILIPPINES. Although the book was nominally fiction, the protagonist and his story were Richardson.

In that book, Richardson’s character, through Wolfert, describes how he organized, armed, and led his people against the Japanese.

“At first, we did it all in the villages, making all our supplies in impromptu workshops. We used hack saws, hand files, plumbing pipe, tape, nails, and materials stolen from the Japanese supply depots.

“In one 10×20 ‘factory,’ we even had a hand forge. There, we made shotguns, some rifles, and all of our ammunition. All of it was from homemade ingredients, and all of it was done by hand.”

Hollywood turned Wolfert’s story of Richardson’s heroics into a film, starring Tyrone Power, in 1950. However, his real story was more deadly interesting than the reel one.

For example, the first ambush with the homemade shotguns was in early February of 1942, and netted Richardson’s band of eight men and two women five Japanese rifles, one submachine gun, and a few hundred rounds of ammunition.

“We got hand grenades and more ammo from the soldiers we ambushed on the second try a week later. We got a light machine gun and more small arms the third time. We now had enough real arms to make real raids,” Richardson reported.

Jungle telegraph word of Richardson’s success spread, as did the number of small groups under his nominal command, all using the same tactics. In addition to killing Japanese troops and taking their weapons, equipment and food, these tactics were forcing the enemy to utilize more troops to find the shifty irregulars; the first step to not losing a guerrilla war.

At that point, toward the end of 1942, Richardson’s group became a vital link in organized guerrilla activities, not only in Leyte, but also in all the islands. The U.S. Navy promoted him to Lieutenant and in addition to his U.S. Navy rank; he was also a Major in the Philippine Army.

The experts recognized Richardson’s impact.

“The propaganda slogan of the Japanese sweep through the Pacific had been one of racial nationalism, ‘liberating their racial brothers from the exploitation of their white colonial masters.’ While the idea was successful in some parts of Asia, heroes like Lt. Richardson stopped it cold,” was the assessment of Major General Edward Lansdale, a military icon in that region.

He added, “There was little question of the Philippine/American friendship and loyalty. The Japanese came on so very heavy handed that their racial stuff didn’t work. So they resorted to their old tactic from China, terror, torture and horrible death for all in their path.”

The historian Trevor Dupuy wrote, “The Philippine people are proud, freedom-loving, and independent. During WWII, man for man and woman for woman, they fought harder against an occupation enemy than any other nation.”

Yes, the Japanese were cruel and harsh. But so were the guerrillas. It was that kind of war.

“When the nationalism didn’t work, the Japs really put on the direct pressure, lots of terror killings, civilian hangings, and heavy, hunt and kill patrols,” Richardson said.

“They also told us by radio that Gen. Wainwright had surrendered all American forces and that the only honorable thing for us to do was to surrender. They promised us good treatment. But, by then we already knew about Bataan and the death march.

“Later, they said they would kill surviving prisoners from Bataan and Corregidor unless we came in,” Richardson said.

Feeling an obligation to honor, a few senior officers did surrender. The younger ones, like Richardson, were cynical, and stayed to fight, as they did not believe the Japanese…who were lying, and killed the prisoners anyway.

“We learned, too, that Lt. Col. Martin Moses and Lt. Col. Arthur Noble and a few of our key men had escaped from Bataan and were determined to build an even stronger resistance movement. That was very good news,” Richardson added.

By October of 1942, Gen. Douglas MacArthur urged Resistance units to “strike whenever and wherever possible” at the enemy. He also established submarine supply and communication plans for the irregulars who remained behind enemy lines.

“We’d been operational way before October. But, I was glad to hear about the supplies. We were getting low on captured material and had little powder for our homemade guns,” Richardson remarked.

Not only didn’t enough supplies arrive, but by a stroke of bad luck, the Japanese captured both Colonels Moses and Noble in May of 1943. The officers were beheaded publicly.

“The Japanese also offered great sums of money to locals for informants, especially to turn in Americans. But there were only a few isolated cases. The Philippine people were wonderfully loyal to us, and to their own freedom,” Richardson explained.

Richardson said, “The Japanese had played the racial issue all through WWII, trying to convince these native peoples in each nation they invaded that they were there to save them from American and British colonial masters. What damned nonsense.”

However, coupled with the Japanese brutality, this racism, plus monetary rewards, did create collaborators among the local population. This did not sit well with the guerrillas. According to most experts, in general, Filipino people are usually mild and peaceful folks. Aroused or engaged, like any of us, they can become fearfully vindictive and brutal.

Richardson recalled one instance where guerrillas on Leyte caught some of their countrymen cooperating with the Japanese to kill both Americans and Filipino leaders. He said the guerrillas minced the captured Filipino collaborators alive, and floated the pieces downstream, into their home village. He said there were far worse events that he heard about.

The relentless Japanese pressure never broke the guerrilla movement. By late summer of 1943, Col. R.W. Volckmann took command of the guerrilla units and re-established communication and supply networks, increasing combat efficiency, and morale.

“Not only did Col. Volkmann do that, but also he pushed MacArthur to send along the supplies he’d been promising, finally! We started to get both regular air drops and submarine supplies that included the latest equipment and weapons,” Richardson recalled.

“By early 1944, we were certain the allied invasion wasn’t far off. We really intensified our counter-terror campaign against the Japanese.

“Finally, we got coded radio messages that the invasion would be on the eastern shore of our island, Leyte. Our units were given more arms and supplies, and told to get more recruits so we could support the invasion force,” Richardson said.

Amazingly, Richardson wrote a 200-page personal diary, typing duplicate pages on an antique typewriter on his rare breaks. One finished copy was buried by priests in a Mindanao church yard, after sealing it in a bamboo box. He gave the other copy to the Navy brass upon the full liberation of the Islands in 1945. Following WWII, the priests returned that copy to Richardson.

Coma Richardson, his wife of 56 years, says, “That original manuscript is in remarkable condition. We gave it to the Nimitz Museum in Fredericksburg, TX for their archives.”

Mrs. Richardson, a charming and delightful lady, said that friends and family members would like to see Lt. Richardson’s original diary published, verbatim, for the pure reality of daily life in the guerrilla life. She says it is more starkly realistic that the novel of her husband’s incredible experiences.

On October 21, 1944, Gen. MacArthur waded ashore on Leyte, the day after the U.S. Sixth Army had landed. He announced, “People of the Philippines…I have returned. By the grace of the Almighty God, our forces stand again on Philippine soil. Rally to me! Rise and strike!”

A bemused Iliff Richardson said, “That sure was pompous grandstanding for the newsreel cameras. We guerrillas have been rising and striking for three long years already!”

All over the Islands, guerrilla units fought side by side with regular forces to finally defeat the Japanese, who didn’t give up easily. The Allies encouraged the guerrillas already behind Japanese lines to step up their favorite tactics of assassination, ambush, destruction of supplies, terror, and cutting communications. Slowly and painfully, the Japanese rolled back.

“By January of 1945, our irregulars were in the front line that moved into Luzon. When the Japanese finally surrendered the Philippines, the Allied unit nearest their major headquarters was our guerrilla band,” Richardson said proudly.

“Considering what we started with, I’d say that victory was truly ours,” added this real American guerrilla in the Philippines.

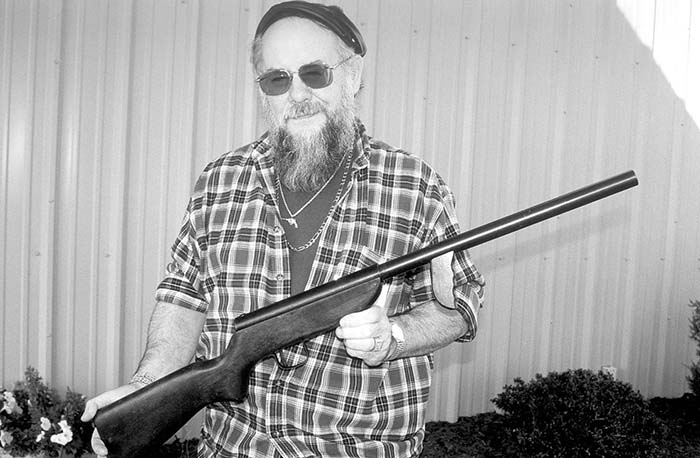

Following the war, Iliff D Richardson returned to Texas, married, raised a family, and began a civilian career with Northwestern Life Insurance Company, after his brief fling with that civilian version of his guerrilla shotgun. He also worked as a motivational consultant to corporations and government agencies.

He never returned to the Philippines to visit any of his former wartime comrades. As Coma Richardson says, “Rich told me that once the war was over, it was over, and he was ready to move on with our life together.”

In honoring Richardson after the liberation of the Philippines, Col. Kangleon said of his American friend, “He was the light that led MacArthur back to the Philippines.”

Yet, Iliff Richardson has no ship nor other USN facility named after him for his accomplishments nor is anything likely to be named in his memory. He wasn’t a lifer, a careerist, and he survived the war. He did his duty, wow, did he do his duty, WAY above and beyond the call of that duty.

When Iliff David Richardson passed away at age 83 on 10 October, 2001 in Houston, Texas, local journalist Chuck Hlava wrote, “Richardson had courage, brains, organizational skills, charisma and character. They don’t make them that way anymore…He left a legacy of bravery and ingenuity like no other.”

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V7N11 (August 2004) |