By Frederick Clifford –

In 1915, the Italian Army became the first to adopt a submachine gun, with the twin-barrelled 9mm Villar Perosa, designed the previous year by Col. Abiel Revelli and produced by RIV Officine di Villar Perosa, a small subsidiary of the larger, well-known FIAT factory in Turin. The Villar Perosa (contemporaneously referred to as the Revelli, FIAT, or O.V.P.) consisted of two tubular receivers affixed adjacent to one another, taking two 25-round magazines in overhead feeds, fired from a pair of spade grips fitted to the rear of the gun. It was designed to be fired from a mount – originally a twin-legged shield or a tripod, but later a bipod – as a crew-served light support weapon, with a gunner and three ammunition carriers. Therefore, the Villar Perosa was not really a “submachine gun” as we understand the term today, but nevertheless it coined the equivalent Italian term, “pistola mitragliatrice.”

The Villar Perosa did enjoy some success during World War I, with around 15,000 units produced and fielded extensively by the Italians in their war against Austria-Hungary, who even fielded their own copy in 9x23mm, known as the “Sturmpistole.” However, the physical limitations of the Villar Perosa prevented it from fulfilling its full potential as an assault weapon. This was soon to change as the weapon would be adapted into a shoulder-fired infantry carbine.

In December 1916, the Italian Army oversaw tests of a new weapon, based on the Villar Perosa. This was the FIAT submachine gun, designed again by Col. Revelli collaboratively with FIAT of Turin and RIV-OVP of Pinerolo. The gun consisted of a single, largely unmodified Villar Perosa receiver, mounted onto a wooden stock with a conventional trigger and three-position fire selector switch, thus creating one of the very first conventional submachine guns in history. Further tests of the FIAT submachine gun took place in January 1917 and the Italian Army became invested in this new concept. A requirement for a new weapon of this type was declared and several industrial firms were commissioned to develop and submit similar prototypes for comparative trials. The three main firms participating in this competition were FIAT (whose prototype has been described), Ansaldo, and Beretta – companies who were already involved in the manufacture of the Villar Perosa to varying degrees. Submissions from SIAI Savoia and the Aviazione Navale were also reportedly developed, as well as a design by Capt. Amerigo Cei-Rigotti, however the records concerning these models are few and far between.

Pietro Beretta entrusted the design of his company’s submission to Tullio Marengoni. Although often described as young when he began work on the Beretta carbine, Marengoni was in fact 36 years old in 1918 and had already been working at the firm for practically all of his adult life. He rose to prominence in the firm almost entirely through his connections – he was a childhood friend of Pietro Beretta’s nephew, and had no formal training as an engineer. But despite his lack of qualifications, Marengoni proved himself nothing short of a self-taught prodigy in the field of gunmaking and was probably the most exceptional designer ever employed by Beretta.

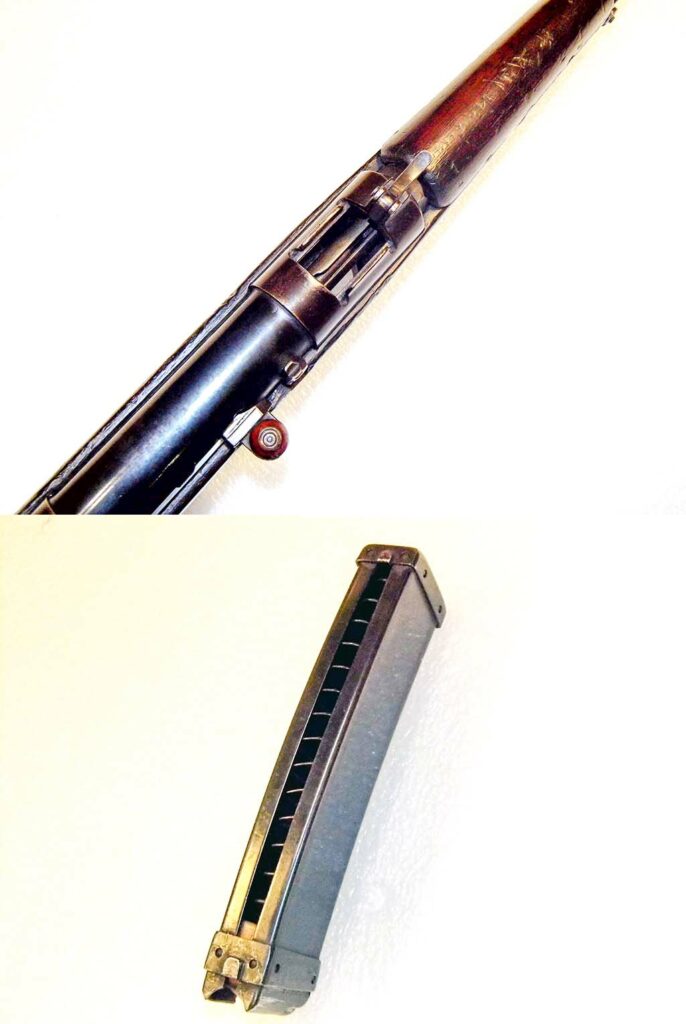

In designing the Beretta Model 1918 carbine, Marengoni demonstrated his technical efficiency by making extensive use of components from existing weapons. Not only was the receiver taken from the Villar Perosa, but the furniture was lifted from the obsolete Vetterli rifle, as is especially evident from the distinctive trigger guard. In most models, the fore-end was only half-stocked, with the partially exposed barrel mounting a folding spike bayonet, of the type used on the Carcano M91 carbine. The bayonet swivel, situated underneath the muzzle, was built with a locking switch. On rarer examples of the Model 1918, the fore-end was fully stocked with no integral bayonet, but instead had a mount, taken from the Carcano M91TS carbine, for a detachable bayonet. Marengoni’s intuitive recycling of components from the Vetterli, Carcano, and Villar Perosa resulted in a weapon which employed relatively few original parts of its own, lessening the production time considerably.

A key misconception about the Beretta Model 1918 is that it was a submachine gun. It may come as a surprise to some readers that this is not the case, despite it having been long described as such by experts like Nelson & Lockhoven. In fact, the standard Model 1918 carbine was a self-loading carbine, with only semi-automatic capability. Twin-trigger models with automatic capability were made, but only in small numbers on a very limited basis; these models were not made by Beretta, but by Manifattura Italiana d’Armi (M.I.D.A.) of Brescia. Experimental models with fire selector devices were also tried, including a particularly unusual model with a piston-like buffer connected to the bolt handle. However, the typical, single-trigger version that is most commonly depicted was not capable of automatic fire.

In the Model 1918, as with the Villar Perosa, a delayed blowback action was employed in which the bolt guide was interrupted by a 45-degee cam at the forward-most point of the cocking slot. This forced a rotation of the bolt before it blew back, creating – in theory – a delay in the style of the Blish lock used in the Thompson gun. The reality is, much like the Blish lock, the delay was negligible and had no appreciable effect on automatic fire. Since the standard model Revelli-Beretta fired in semi-automatic only, there was no particular advantage gleaned from this system; regardless, the Villar Perosa’s action was retained with little modification.

The magazine feed of the Villar Perosa was also basically unchanged, taking the same 25-round mags from an overhead position, although the magazine catch was of Beretta’s own design. Due to the placement of the magazine, the sights were offset to the right side of the receiver, much like the later Owen gun. Villar Perosa magazines were designed with a windowed slit on the rear side, allowing the user to easily check their remaining rounds; especially useful considering the rear of the magazine would always be in view of the firer. The downward-facing ejection of the Villar Perosa was retained, although now encased within a distinctive rectangular chute. Variances could also be found in the pattern of buttstock; most were built with straight-hand stock, but some other examples feature a rounded pommel grip.

Although the Beretta Model 1918 is usually stated to have been chambered in 9mm Glisenti, the then-standard Italian pistol cartridge, this is actually only half-true. Both the Villar Perosa and the Beretta were designed to fire a special variant of the Glisenti cartridge with a higher load than the standard version that was used in pistols. This modified cartridge, now extremely rare, fired at a velocity roughly equivalent to the German 9x19mm Parabellum cartridge. Consequently, the Beretta may fail to discharge when loaded with the standard Glisenti pistol cartridge. The Glisenti and Parabellum rounds are, however, so dimensionally similar that it is possible to load and discharge the Beretta with 9mm Parabellum – however it should be stressed that it is not actually designed to fire this cartridge.

The FIAT, Ansaldo, and Beretta prototypes – referred to as “moschetti automatici,” or “automatic muskets” – underwent trials in 1918. While small quantities of the FIAT and Ansaldo guns, which were both selective-fire submachine guns, were apparently issued on the front for field tests, it was the Beretta gun formally taken into service by the Italian Army that year. It received the official designation “Moschetto Automatico Revelli-Beretta”, with Col. Revelli receiving a shared credit in the nomenclature presumably because the gun was operating on the Villar Perosa action, which was protected under his patent.

In September 1918, Beretta secured the patent for the Model 1918 and subsequently received confirmation from the Italian army that they would immediately receive 5,000 Villar Perosa submachine guns to be converted into 10,000 Revelli-Beretta carbines. Production commenced in these last few months of the war, but was prematurely cancelled at the end of November, a matter of weeks after the signing of the armistice. The end of the conflict meant the requirement for the Revelli-Beretta carbine practically disappeared overnight, and it’s estimated that only about half of the agreed 10,000 weapons were actually assembled and delivered to the army. These guns were distributed at a limited rate of 18 units per battalion, specifically issued to the best marksmen of a given company, and while some Revelli-Berettas may have seen active use during the climatic Italian offensive at Vittorio Veneto at the end of October, it is a point of contention as to whether the gun was ever used in combat in 1918.

the Villar Perosa was not really a “submachine gun” as we understand the term today, but nevertheless it coined the equivalent Italian term, “pistola mitragliatrice.

Almost immediately after the end of the Great War, the Revelli-Beretta’s performance came under scrutiny. These concerns were not so much levelled at the gun itself, but rather the entire concept of pistol-caliber automatic carbines and submachine guns. The Revelli-Beretta and Ansaldo guns were subjected to renewed tests and it was decided that they would be replaced by a new intermediate-caliber, selective-fire carbine that could fulfil both the roll of the submachine gun and the infantry rifle. In 1922, the state arsenal at Brescia actually developed a modified version of the Revelli-Beretta in the intermediate cartridge, with automatic fire capability and a reworked clip-feed system taken from the FIAT-Revelli machine gun. But this prototype, and the intermediate carbine project as a whole, soon floundered and had been completely defunded by 1928.

In 1930, Beretta developed a new version of the Model 1918 carbine known as the Model 1918/30. On a technical level, the Model 1918/30 had little in common with the original Revelli-Beretta, with the method of operation completely revamped. The Villar Perosa action was entirely eliminated and replaced with a closed-bolt system of Beretta’s own design. It featured a new type of bolt with a separate spring-loaded firing pin that was retracted by a ring-shaped piece protruding from the rear end of the receiver (hence the gun was nicknamed “Il Siringone”, or “The Syringe.”) The magazine feed was relocated to the underside of the receiver, freeing up the weapon’s line-of-sight, and new proprietary straight box magazines were used instead of the old Villar Perosa magazines. All aspects of the design that were derived from Abiel Revelli – who had passed away the previous year – were now gone, and his credit was removed from the gun’s nomenclature, with it simply being known now as the “Moschetto Automatico Beretta.”

Most Model 1918/30s were produced by manually converting existing Model 1918s, which can perhaps go some way as to explaining why there are so few surviving original Revelli-Beretta carbines. The Model 1918/30 was sold in quantity to the Italian police, particularly the Forestry Corps, and also achieved export sales to Argentina where it was adopted by their federal police. It was produced under license in Argentina by HAFDASA, and also served as the basis for several designs by Halcon in the 1940s.

In spite of the new Model 1918/30 variant, Italian military requirement for the Revelli-Beretta carbine had long since passed by the 1930s and it was considered obsolete. The Italian Army sold these guns as surplus to Saudi Arabia and Ethiopia; in the latter instance, they were issued to Haile Selassie’s personal guard, the Kebur Zabagna, and, ironically, used against the Italians when they invaded Ethiopia 1935 to 1936. A direct consequence of this is that, after the swift collapse of the Ethiopian army, the Italians re-captured stocks of these old weapons and pressed them into service yet again. Reportedly these guns were still in use when the British arrived in North Africa in 1940, as the far superior Beretta Model 38 would not come into general issue until 1941. However, the majority of Revelli-Berettas that saw use during World War II were likely lost amidst the collapse of the Italian forces in Ethiopia; by 1942, the Italian board of ordnance reported that there were only 60 still left in service, effectively ending issue of this antiquated weapon for good.

The legacy of the Revelli- Beretta carbine is a quiet one, as it has historically been overshadowed by the more impactful Bergmann M.P.18,I submachine gun adopted by the Germans at the end of World War I. However it did have some influence on certain post-war SMG projects, such as the Netsch carbine, developed in Czechoslovakia in 1919, and the STA submachine gun briefly adopted by the French Army in 1924. More importantly, the Revelli-Beretta was the first step in the development of Tullio Marengoni’s subsequent submachine guns, leading up to the excellent Beretta Model 38 series. Today, original 1918 Beretta carbines are exceedingly rare, usually only found in museums; the later Model 1918/30 variant is somewhat more numerous, with some examples having made it to the American civilian market. As recently as March last year, the Italian gun dealer Nuova Jager reported they would be importing and restoring a batch of original Beretta carbines – both 1918 and 1918/30 models – from Ethiopia, where they had been sitting in storage for many decades.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V26N1 (January 2022) |