By Frank Iannamico

Smith & Wesson

The Smith & Wesson Corporation is one of the oldest firms in the United States and is still actively in business. Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson joined forces in 1852 to develop a repeating firearm. By 1857, the company employed 25 people. During that year, a total of four revolvers were manufactured. The U.S. Smith & Wesson Corporation has long been recognized for producing some of the finest revolvers in the world. Many served the United States and the Allies with distinction during World War I and World War II.

Smith & Wesson (S&W) began the development of their Model N Hand Ejector revolver in 1905. The large frame revolver was originally designed for the .44 Special cartridge. The first model was also known as the “Triple Lock;” the name referring to a third locking lug on the cylinder crane. The third locking mechanism was thought to be necessary due to the increased power of the .44 cartridge.

During World War I, the British Ministry of Munitions contracted with Colt and S&W in 1914 to manufacture revolvers chambered in .455 Webley in order to supplement a shortage of their Webley Mk VI revolvers. Smith & Wesson manufactured approximately 75,000 of its high-quality Second Model, Hand Ejector, double-action revolvers in .455 caliber for Great Britain and Canada. The S&W revolvers were adopted as “substitute standard,” designated as the “Pistol Smith & Wesson .455 with 6.5-inch barrel Mark I.” The British considered the extra locking lug redundant and requested it be eliminated from the design. Subsequent orders, lacking the third locking lug and ejector shroud, were known as the Mark II. As the U.S. prepared to enter the First World War, there were no additional British contracts, as production shifted to the U.S. to arm a rapidly growing U.S. Army.

In anticipation of America’s eventual involvement in the conflict, the factory increased its efforts to develop a revolver chambered for the standard U.S. service .45 ACP cartridge. The U.S. Army tested a S&W Hand Ejector revolver configured to fire the standard .45-caliber round during 1916–1917. After testing, the revolver was deemed satisfactory for military use; with this endorsement, S&W began tooling up for large-scale manufacture of the U.S. Model 1917 .45-caliber, double-action, six-shot revolver.

Early Production M1917s

Early production of the S&W M1917 revolver featured hammers with fine circular grooves. The Army felt as though the milled grooves would collect dirt and possibly cause malfunctions. As per the Army’s request, subsequent production hammers were smooth. Other features of early production were wooden grips that were dished at the top; these were also eliminated, replaced by full-rounded wood grips. Early revolvers had a round top strap and a rear sight with a small U-shaped notch. Later manufacture, post-WWI civilian production, had a flat top frame with a square-shaped notch for the rear sight. The revolvers were finished in a low-gloss blue, with a color case-hardened trigger and hammer. A 5.5-inch-long, 6-groove barrel had a right-hand twist of one turn in 14.659 inches. A lanyard ring was placed at the bottom of the weapon’s butt. The overall length was 10.79 inches. The S&W revolver was slightly lighter at 2 pounds, 4 ounces than Colt’s 1917 model that weighed 2 pounds, 7 ounces.

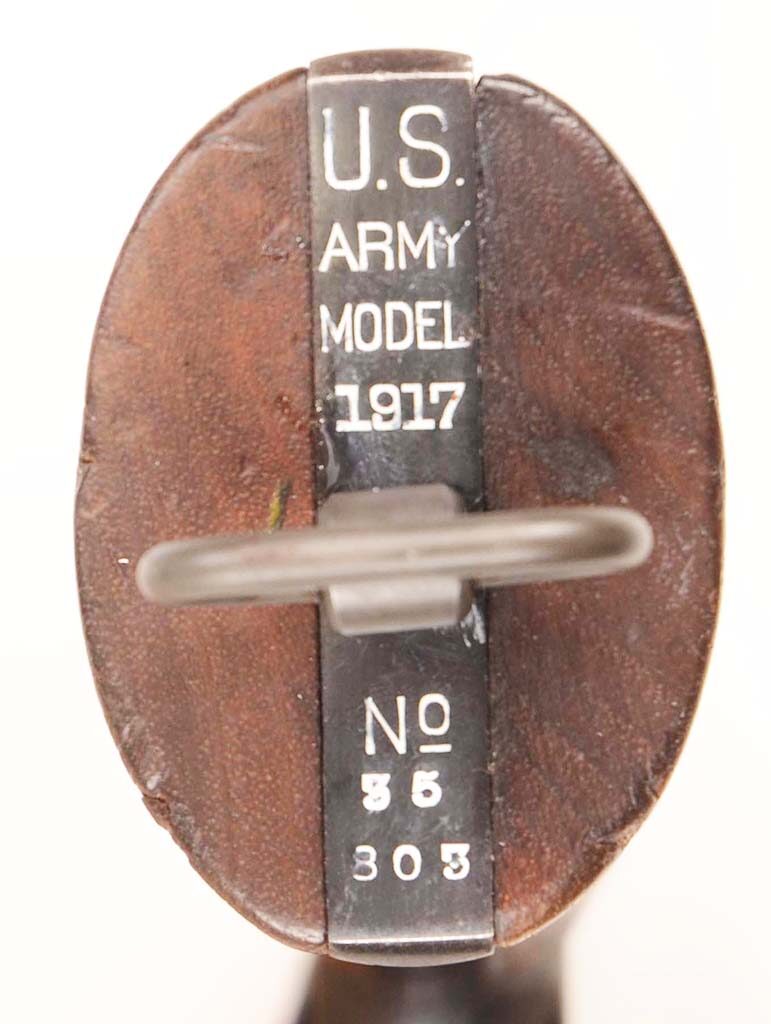

The original government contract price for each revolver with two clips was $14.75. The price was later increased to $15.60. Spare barrels were priced at $5.58 each. S&W production ran from October 1917 until January 1919, with approximately 163,635 Model 1917 revolvers manufactured. Serial numbers were placed on the butt, cylinder, underside of the barrel, rear of the yoke and in pencil on the inside of the right wood grip. Along with the serial number, the butt was marked: “U.S. ARMY MODEL 1917.” The top of the barrel was roll-marked “SMITH & WESSON SPRINGFIELD MASS U.S.A. PATENTED DEC. 17, 1901, FEB 6, 1906, SEP 14, 1909.” The left side of the barrel was marked “S&W D.A.45.” The bottom of the barrel was stamped “UNITED STATES PROPERTY.” A provisional inspection mark on early component production was a letter “S,” reported to be the mark of Gilbert H. Stewart. Later production used the eagle’s head with a letter and number code: “S2,” “S3,” etc. The S&W trademark logo, normally stamped on its commercial firearms, was not used on the military contract 1917 revolvers.

Note: The number stamped on the butt of the S&W military M1917 is the weapon’s factory serial number. The factory serial number on the Colt-manufactured U.S. Army Model 1917 is stamped on the frame. A different, non-matching number is stamped on the butt; it is not the serial number but is a government control number.

Each assembled weapon and spare barrel were proof-fired in the presence of an Ordnance inspector, using a special high-pressure cartridge. After successfully passing the test, a proof mark was applied to each weapon by the person performing the test. Each revolver was function-fired with six rounds; three in double-action and three in single-action. Weapons were test-fired for accuracy at a range of 15 yards. A 2,000-round endurance test, using standard-issue ball ammunition, was performed on one revolver from each lot. The Army Inspector of Ordnance (AIO) acceptance stamp was “GHS” of Officer Gilbert H. Stewart on early production; later the “flaming bomb” ordnance or the “eagle head” insignia was used to designate government acceptance.

Holsters & Clips

There were three different leather holsters issued to carry the M1917 revolver. The earliest was the M1909 model designed at the Rock Island Arsenal. During World War II, the M2 holster was introduced which was similar to the M1909 holster, except the butt of the weapon was pointed rearward. The WWII M4 holster was similar but had a closed bottom to keep debris out of the muzzle.

Ammunition was issued on the 3-round half-moon clips. During WWI, a three-pocket canvas pouch was supplied to carry two clips in each pocket for a total of 18 rounds. During the post-War period, a handy six-round “full-moon” clip was designed by a S&W engineer. Although the clips are reusable, they can be difficult to load and unload. To eliminate the need for the clips, the Peters Cartridge Company introduced the .45 Auto Rim, also known as the 11.5x23R, in 1920. The rimmed version of the .45 ACP cartridge allowed the Model 1917 revolver to fire and eject all the spent cases without the clips.

During production of the M1917 revolvers, there were a few labor issues at the S&W factory that resulted in the government organization, the National Operating Company (NOC), taking over management of the S&W plant. After the end of WWI and subsequent production of the revolvers for the military concluded, S&W reassumed management of their factory in 1919. After the military contracts ended, there were a substantial number of unfinished revolvers and parts remaining. After the rebuild contracts were terminated, S&W purchased the parts from the government. During the 1920s, civilian production of the N frame revolvers resumed. The commercial 1917 first appeared as a regular cataloged model in “Catalog D-2,” issued in January 1921.

In 1937, Smith & Wesson sold 25,000 .45-caliber Model 1917 revolvers to Brazil, assembled with new manufactured parts and frames. There was a second Brazilian contract for 12,000 additional revolvers in 1946. Many of the components used to assemble the revolvers for the second contract were left over from World War I production; most of the frames and parts have military inspection markings on them.

John Dillinger

A stolen S&W 1917 revolver was used by infamous outlaw John Dillinger, with the serial number and all military markings carefully ground off. Like many of the weapons used by Dillinger, the revolver is in the custody of the FBI.

In the Movies and Television

The S&W Model 1917 revolvers have been featured in films and video games in the hands of both good guys and villains.

There were two different revolvers used by the hero Indiana Jones in the 1981 Steven Spielberg movie “Raiders of the Lost Ark.” The .45-caliber S&W 1917 used in the movie was not a U.S. military contract revolver, as evidenced by the S&W trademark logo on the left side of the frame, absent on military revolvers. The barrel was shortened down to a length of 4 inches. Interestingly, the serial number of that revolver, 172449, falls in the reported range of Brazil’s second 1946 contract for the Model of 1937, a copy of the M1917 revolver.

The other revolver used in the movie was a British-issued .455-caliber S&W 2nd Model Hand Ejector with a lanyard ring and a barrel shortened to a length of 4 inches. This was reportedly the revolver Indiana Jones used in the famous scene where he is confronted in the Cairo marketplace by a black-robed man with an over-sized scimitar. As the man began displaying his skill with his weapon, Indy, desperately preoccupied with finding his kidnapped love interest Marion, simply draws his revolver and shoots the swordsman.

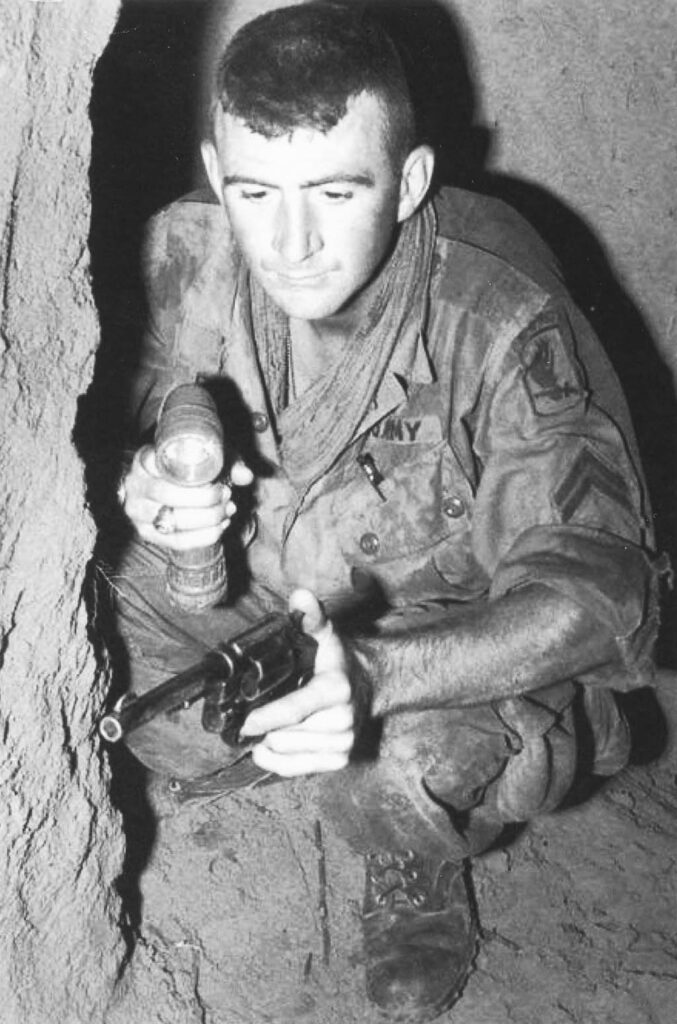

Left: A World War I soldier with a holstered M1917 revolver and a three-pocket canvas pouch that held two 3-round clips in each pocket for a total of 18 rounds. Right: A U.S. Army Corporal from the 173rd Airborne Brigade armed with a .45-caliber, M1917 revolver on tunnel-rat duty during the Vietnam War.

Brad Pitt’s character, Sergeant Don “Wardaddy” Collier, in the 2014 Hollywood World War II movie “Fury” carried a S&W M1917 revolver as his personal sidearm. His revolver sported a set of plastic “sweetheart” grips with the image of an unidentified female. Other films of note that featured the S&W Model 1917: “The Highwaymen” by actor Kevin Costner’s character Frank Hamer; “Hacksaw Ridge”by characters Tom and Desmond Doss; “All the Kings Men”by actor Mark Ruffalo’s characterDr. Adam Stanton.

There is still quite a collector interest in the old .45-caliber 1917 military revolvers. Enough interest that S&W reintroduced a commercial slightly updated version of the 1917 for their Classic Series, designated as the Model 22. There is also a modern version .45-caliber revolver from S&W in stainless steel, the Model 625.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V25N1 (January 2021) |