By Robert G. Segel

World War I, the “War to End All Wars,” was devastating to a large part of Europe and resulted in the loss of an entire generation of men. The unfathomable numbers of death and injury loss from battles and the inhumane life in the trenches in a static war is generally not known or understood today. World War II, with its modern mobile warfare and the advantage of a huge library of film footage, enable the current generation to learn and study in detail the events of the Second World War. But World War I is far in the past, almost 100 years ago, with extremely limited silent film footage that makes it difficult to relate to for today’s media savvy generation. It was the clash of the old world with old world armies and tactics colliding with the fruits of the industrial revolution providing new and efficient methods and means of warfare. The machine gun was the new weapon of mass destruction and tanks and airplanes introduced a new mobility never seen or imagined before. Like the American Civil War, World War I is an area of study relegated to the serious student as opposed to the widespread casual familiarity of World War II. But to the people of France and Belgium, World War I is very much a part of their lives and an integral part of their history. There are museums, monuments and immaculately cared for cemeteries all throughout the region that remind them daily of their past. As we approach the 100th anniversary of the start of that terrible time, we take a look at those memorials to remind us of the ultimate cost.

Albert

The town of Albert (pronounced al-bare) is located in the heart of the Somme battlefields of World War I. Approximately 75 miles from Paris, Albert is a commune in the Somme department in Picardie in northern France with a population of just over 10,000.

In the early months of World War I, fierce fighting was fought in the area with the first enemy shelling beginning on September 29, 1914. The statue of Mary and the infant Jesus – designed by sculptor Albert Roze and dubbed the “Golden Virgin” – on top of the Basilica of Notre Dame de Brebieres was hit by a shell on January 15, 1915 and was put in a horizontal position and was near falling. The “Leaning Virgin” became a familiar sight to the thousands of British soldiers who fought at the Battle of the Somme, many of whom passed through Albert, which was situated just three miles from the front. An administration and control center for the Somme offensive in 1916, the first press message of the “Big Push” originated from Albert. The town was a pile of red rubble and it wasn’t until October, 1916 that the Somme offensive had pushed the German guns out of range of Albert. As civilian residents began to return to Albert to salvage what they could, General Byng made Albert his headquarters while planning the November 1917 attack on Cambrai. In March, 1918, the Germans made a final push in their big Spring Offensive and retook the town. The British, wanting to prevent the Germans from using the church tower as an observation post, directed their artillery bombardment against the Basilica in April 1918 and the Leaning Virgin fell never to be recovered. Albert was retaken on August 22 by the British East Surreys who entered the town at bayonet point and was held by the British then until the end of the war.

Albert was in ruins but was completely rebuilt after the war and the Basilica was faithfully rebuilt according to its original design including the splendid gilt statue of Mary and the infant Jesus at its top.

Somme 1916 Musée des Abris

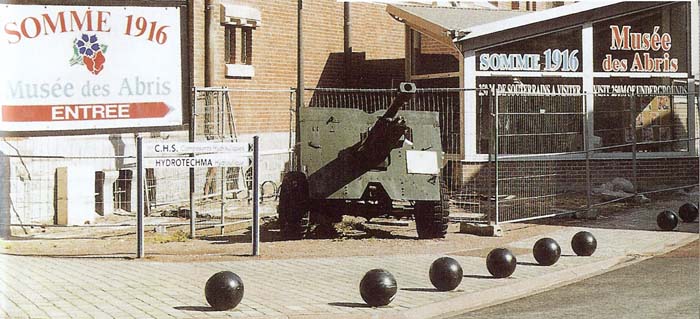

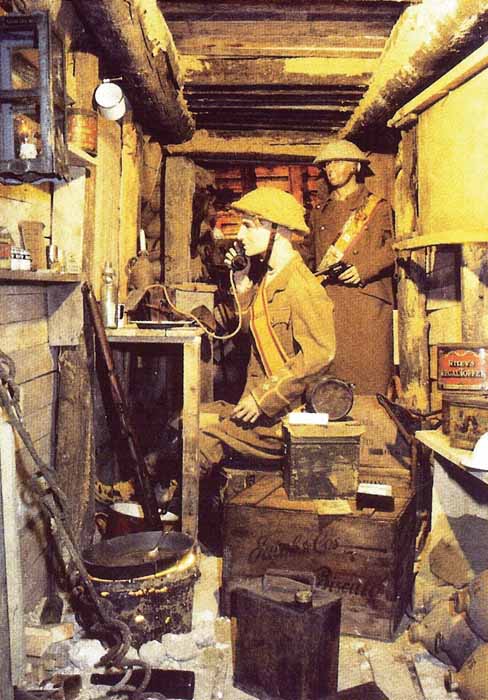

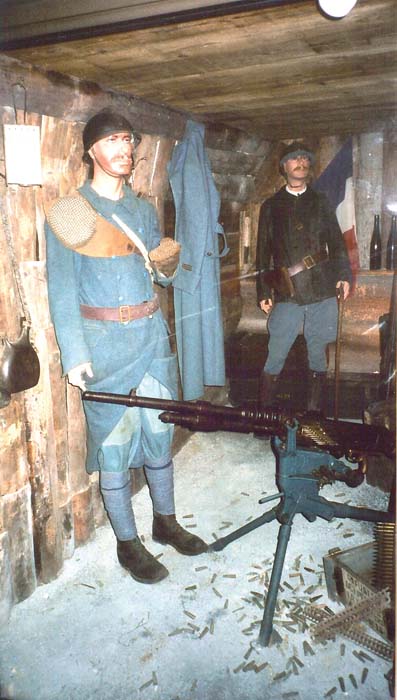

Just off the main town square on Ancient Godin Street, is a small, unassuming “storefront” window with a sign that says “Somme 1916 Musée des Abris (Museum of the Shelters). As you walk in there are some mundane displays of some World War I materiel and pictures on the wall and a mannequin horse outfitted as it would have been during the war: on the whole, not very impressive. But wait; there is a brick staircase that descends ten meters (33 feet) below ground that leads into a series of tunnels and alcoves that represent 230 meters (755 feet) of gallery space and 15 alcoves where you discover the soldier’s daily life in the trenches. The tunnels run beneath the Basilica square and there along the long passages of the tunnels is a marvelous collection of World War I artifacts taken directly from the battle fields that surround the town. Munitions from grenades to artillery shells line the corridor. Barbed wire, helmets, field gear and equipment, personal items, trench art, and weapons are just some of the assortment of all the things that made up life in the trenches and the battles that ensued. In a number of alcoves are mannequins that are set up in recreations of the trench warfare of both sides of the conflict. All the items on display are original equipment taken directly from the battlefields.

Upon exiting the tunnels, one finds oneself at a small souvenir shop in the public gardens several blocks from where you entered.

The museum is open 7 days a week from February 1 until mid December. They are open from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. but are closed for lunch between 12 noon and 2 p.m., though during the summer months they remain open during the lunch period. Entrance fee is 5 Euros for adults, 3 Euros for children 6 to 18, and children under 6 are free.

Additionally, at the Town Hall in Albert, a memorial plaque was presented in 1939 by the Machine Gun Corps Old Comrades Association to commemorate the heroes of the Machine Gun Corps who fell in battle during the Great War of 1914-1918.

Thiepval

Four and a half miles north of Albert is Thiepval with its impressive monument 45 meters high (150 feet) that can be seen for many miles around. The village of Thiepval, in the region of Picardie, was totally destroyed during the war. The present Thiepval settlement is located a short distance to the southwest of the original settlement and has a population of about 100.

The First World War Franco-British Memorial is located at Thiepval. Its 16 pillars bear the carved names of 73,367 British and South African soldiers that fell during the Battles of the Somme between July 1916 and March 1918 and who have no known grave and are known as the “Missing of the Somme.”

The accompanying cemetery at the rear of the memorial unusually contains both British and French burials – 300 of each – to commemorate the joint Anglo-French action, with French burials on the left and British on the right. All the burials bear the inscription “Unknown.”

The monument was opened on July 31, 1932 by the Prince of Wales and the Thiepval memorial was and is the largest British war memorial in the world.

According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, “On 1 July 1916, supported by a French attack to the south, thirteen divisions of Commonwealth forces launched an offensive on a line from north of Gommecourt to Maricourt. Despite a preliminary bombardment lasting seven days, the German defenses were barely touched and the attack met unexpected fierce resistance. Losses were catastrophic and with only minimal advances on the southern flank, the initial attack was a failure. In the following weeks, huge resources of manpower and equipment were deployed in an attempt to exploit the modest successes of the first day. However, the German Army resisted tenaciously and repeated attacks and counter attacks meant a major battle for every village, copse and farmhouse gained. At the end of September, Thiepval was finally captured. The Village had been an original objective of 1 July. Attacks north and east continued throughout October and into November in increasingly difficult weather conditions. The Battle of the Somme finally ended on 18 November with the onset of winter. In the spring of 1917, the German forces fell back to their newly prepared defenses, the Hindenburg Line, and there were no further significant engagements in the Somme sector until the Germans mounted their major offensive in March 1918. Over 90% of those commemorated at the Thiepval Memorial died between July and November 1916.”

Delville Wood Cemetery

Located about 7 miles east of Albert is the village of Longueval and just east of the village is the Delville Wood Cemetery – nearly 1 kilometer square, it is the third largest cemetery of the Somme Battlefield. There are 5,521 servicemen buried or commemorated at Delville Wood Cemetery and is a concentration of several cemeteries and isolated graves of the area. The unnamed graves number 3,590 and represent nearly two thirds of the whole.

Opposite the Delville Wood Cemetery on the other side of the Longeuval-Ginchy road in Delville Wood is the Delville Wood South African National Memorial. This memorial serves as the national memorial to all those of the South African Overseas Expeditionary Force who died in World War I. Some 229,000 officers and men served in the forces of South Africa in the war and of these some 10,000 died in action or through injury or sickness.

According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, “On 14 July 1916, the greater part of Longueval village was taken by the 9th (Scottish) Division and on the 15th, the South African Brigade of that Division captured most of Delville Wood. The wood now formed a salient in the line, with Waterlot Farm and Mons Wood on the south flank still in German hands, and, owing to the height of the trees, no close artillery support was possible for defense. The three South African battalions fought continuously for six days and suffered heavy casualties. On 18 July, they were forced back and on the evening of the 20th the survivors, a mere handful of men, were relieved. On 27 July, the 2nd Division retook the wood and held it until 4 August when the 17th Division took it over. On 18 and 25 August it was finally cleared of all German resistance by the 14th (Light) Division. The wood was then held until the end of April 1918 when it was lost during the German advance, but was retaken by the 38th (Welsh) Division on the following 28 August.”

Lochnager Crater

Two miles east of Albert is the village of La Boisselle, site of the Lochnager Crater, the largest British mine crater on the Western Front. In preparation of the 1st Somme offensive, several mines were dug (the Lochnager Crater was named after the trench from where the main tunnel was started) under the German front line positions and on July 1, 1916, at 07:28, two minutes before the start of the offensive, two charges of ammonal explosives of 24,000 and 30,000 pounds (nearly 26 tons), were detonated, crating a crater 300 feet across and 90 feet deep. The explosion sent an earth column of debris nearly 4,000 feet into the air and could be heard all the way to London.

Units of the 34th Division attacked this area and the nearby village of La Boisselle, which was in the Germans hands. This formation contained two whole brigades of “Pals” battalions – the Tyneside Irish and the Tyneside Scottish. They suffered heavy casualties that day with five battalions losing over 500 men each. The whole division lost 6,380 men that day. The entire attack was without success, for by the time the attack was made following the explosion; the Germans had regrouped and repelled the oncoming British. However, the Worchesters took the area around the crater two days later on July 3.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V13N9 (June 2010) |