By Virginia Ezell

A Visit to the Izhevsk Machine Plant

I got the official call in September. Our friends at the AK factory in Izhevsk had everything organized for a special celebration in November. The factory, in fact the town of Izhevsk, was planning to commemorate a very special anniversary. For the workers at the Izhevsk Machine Plant known around the world as IZHMASH, 1997 marked the 190th anniversary of the founding of the factory on the Izh River. For Mikhail T. Kalashnikov it represented the 50th anniversary of his most famous weapon, the AK-47 assault rifle. For those of us privileged to be invited to take part, it was another chance to meet with the world famous designer, and in my case to show my regard for his friendship toward myself and Ed Ezell who respected him so much.

As the day of departure approached the numbers of our group began to firm up. The crew included Masami Tokoi, from the Japanese publication Gun magazine. We had traveled together to the same location at about the same time of year just three years ago, to celebrate M.T. Kalashnikov’s 75th birthday. In addition to these two, we were looking forward to catching up with Carlos Davila, Smith & Wesson’s international marketing representative for Eastern Europe and Africa, and Robert Stutler, the general manager at Sturm, Ruger Co., Inc., in Prescott, Arizona. Kalashnikov remembered his good friends from the Northern Virginia Gun Collectors Association who had so generously assisted in Kalashnikov’s first visit to the United States. He invited the whole club to come. Of those members, Bill York was the only one to sign on to the trek. Later in the adventure in Izhevsk we would meet up with Klaus Muller, a German entrepreneur and museum curator, who had become acquainted with Kalashnikov during one of the latter’s trips to Germany.

I traveled to Moscow. Emerging from the customs hall at the Moscow airport, we found the welcome face and familiar lanky frame of Valery Mokin, the senior man from Izhevsk Mechanical Plant’s Moscow office. To save gas and energy we waited a few hours for Tokoi’s flight from Tokyo, and then went on to the hotel at the Center for International Trade Scientific and Technical Cooperation with Foreign Countries (the “Mezhdunarodnaya”). We were told on our last visit that Armand Hammer had the hotel built during the Communist era to meet international standards foreign travelers and businessmen expected. Compared to some of the surrounding buildings the Mezhdunarodnaya is a nondescript structure, like so many international Hilton-type hotels. Located on the Moscow River it is not far from the White House and across from the Hotel Ukraine, one of “Uncle Joe” Stalin’s ideas of what a hotel should be like. It is a massive structure straight out of a “Ghost Busters” film set.

Mokin deposited the three of us and went back to the airport to get Davila. Stutler would be joining us in Izhevsk within the next few days. Once the threesome became four, we had our dinner, and despite the eight hour time difference of Moscow, went to our respective rooms to try to get some sleep. The next days would be long ones. After breakfast the following day, we met with Mokin’s assistant, André, who agreed to show us some of Moscow before depositing us on the train to Izhevsk that afternoon. We saw several of the newly renovated churches. Whatever the conditions of the individual or the solvency of the Russian Federation itself, the Russian Orthodox Church seems to be doing all right. Donations from all parts as well as government support have led to renovation and in the case of the Church of Christ the Redeemer reconstruction. Gleaming onion domes and bright colors can be seen all over the city. In the before time, Stalin closed the churches. Members of the church were banned from “the party.” He tore the Church of Christ the Redeemer down and put in a swimming pool. Russian President Boris Yeltsin and the well-connected mayor of Moscow put it back.

André then offered to take us on a windscreen tour of the city that had been celebrating all year the 750th anniversary of its founding. He showed us where the old KGB headquarters complex still stands including the infamous and rather undistinguished looking old Lubianca prison. The KGB headquarters of Moscow is just down the street. We passed by the Ministries of Defense, Foreign Affairs and Agriculture before André offered to take us to Red Square. Masami and I had never been to Red Square. It was cold, and beginning to snow as we got to the sight of Lenin’s Tomb. The red star still hangs over the square, although André told us, with what seemed to us a bit of disapproval in his voice, a decision had been made to replace it with the new national symbol of the double headed eagle. Like so many people, it seems as though the Russians would like to erase their past rather than face it, so they reinvent themselves with new flags and symbols.

We had little time to contemplate the changes before we had to be at the train station where we would meet Mokin who had spent the morning arranging for our train tickets. We arrived to find him waiting in the cold, red faced and agitated since we had only a few moments to gather our things and get on board. The train to Izhevsk was full so we were traveling to a town not far from Izhevsk. The overnight ride would take nearly 24 hours. Knowing that in advance, we had purchased some provisions at the convenience store in the hotel complex, but not the kind to sustain us through to the following morning. We had hoped to buy something from one of the vendors on the platform but were disappointed to find there was not enough time to get more substantial supplies. No problem, (Mokin’s favorite English phrase), we thought, we will get dinner on the train.

The three of us shared two compartments. Unlike the rest of Europe, first class compartments on Russian trains do not discriminate so it is possible for men and women to share the same compartment. In the interest of practicality this can mean putting complete strangers of opposite sexes together. Ours was a party of four so we shared two compartments. At least we knew our roommates.

Dinner on the train became an added adventure none of us had planned on. Between the four of us, we could put together four Russian words meaning hello, good bye, thank you and please. Reading each letter was laborious as well. That we managed to get the hot beef soup and warm rolls was evidence of Masami’s ingenuity and their experience traveling to exotic places. Later that evening, Masami went off to have a smoke. Russians do not allow smoking in the compartments or in the corridors. Smokers are relegated to the Siberian-like frigid spaces at each end of the car. There he met a Russian fellow traveler who tried to explain that soon we would be arriving in a town famous for its craftwork. We understood this to mean lace or embroidery, but when the train did stop we saw scores of people on the platform trying to sell crystal products of all sorts. They were offering everything from vodka glasses to crystal chandeliers. All of it was produced in the factory in town. One of the conductors explained that the factory paid its workers with their own output rather than money, so to get cash they tried to sell it to passengers when the trains pulled in. It was after ten o’clock at night, but they waited, their anoraks and fur hats protecting them against the freezing temperatures, for the chance to sell something to one of the train passengers passing through. A set of six cut-crystal vodka glasses cost 35,000 rubles, the equivalent of something over five U.S. dollars.

A night train across the open spaces that divide the center, Moscow, from the rest of Russia is a wondrous experience. The added value in this adventure was the company we kept. The four of us sat in one of the two compartments with Carlos exchanging “war” stories. They have similar experiences traveling in Central America. We went to sleep, or at least to lie down, late. With the lights out, the clear skies of open Russian country the stars were brighter than I could remember seeing outside of a planetarium. Through the darkness you can still see what appears to be isolated villages and farms illuminated with single acre lights. It looked like Kansas. The dusting of snow along the way let us know winter was near by.

On our arrival in the town with a name that sounded like “Agrees,” Elena Kalashnikova, M.T. Kalashnikov’s younger daughter, and Mikhail Dragunov, son of the famous designer Yevgeniy Dragunov, greeted us with a company van. We drove directly to the Izhevsk Mechanical Plant (IZHMECH) headquarters where we met with the chief designer and other senior leaders from the factory and various government agencies who also would be participating in the celebrations of the coming days.

Masami and I had been here before, to attend Kalashnikov’s 75th birthday celebrations in November 1994. Driving around the city of Izhevsk we could see signs of increased wealth or at least evidence of the impact of capitalist reforms since our last visit. In an area on the outskirts of town, about 20 to 25 large single family homes more typical of more exclusive suburban Washington, D.C. than a Siberian city, are being built. It was suggested that some of the directors at the various plants could afford the estimated $500,000 price tag. There are more new cars, many of them imported.

Izhevsk is home to more than 650,000 souls. It is the main city of the Independent Republic of Urdmurtia which has a total population of over 800,000. There are over 20 factories in the town, most of them part of the old military-industrial complex. Similar to other cities in Russia today, there are now nightclubs, private restaurant clubs, casinos, supermarkets stocked with foreign foods, and shops with advertisements in the windows to show their products to consumers. We saw several flea markets where we were told most people do their shopping. These are open-air markets of small individual colorful tent-like booths reminiscent of a small county fair. Apparently these flea markets are open year round because there was already snow on the ground in the first week of November with no thaw in sight before the next April or May.

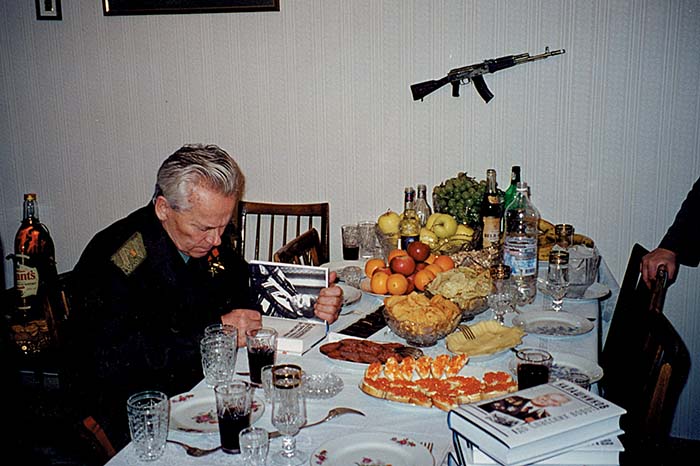

Later in the day we met M.T. Kalashnikov at his apartment where he was autographing copies of his new autobiography for some local government officials, including the President of the Republic of Urdmurtia, of which Izhevsk is the main city and capital. We later learned that the role of President is akin to that of governor of a state in the United States. We toasted each other’s good health and congratulated Kalashnikov on the anniversary of his achievement and to the success of his new book. He then was off to some other function of which there would be many over the next few days.

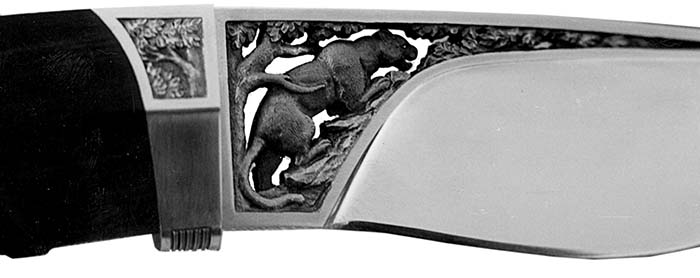

Meanwhile Elena Kalashnikova wanted us to meet some of her friends. We went to a small “art gallery” she had created, having commandeered several of her bosses offices at the local telecom company where she works as a computer specialist. Each of the artists displayed incredible talents, in everything from religious iconography to lacquer boxes and exquisite traditional fairy tale illustrations. One young man, Serguei, makes handcrafted presentation hunting knives with detailed hand-carved wooden handles and sheaths, some of them with inlaid silver. Each of the blades had intricate engravings; each of them was unique. Most were in their own presentation boxes with hand carvings in the same motif as the knife and sheath inside. The skills and artistry of these young people were impressive, but in an economy in which most people find it difficult to support their daily needs, it was clear that the fruits of these artists’ labor could easily be allowed to wither.

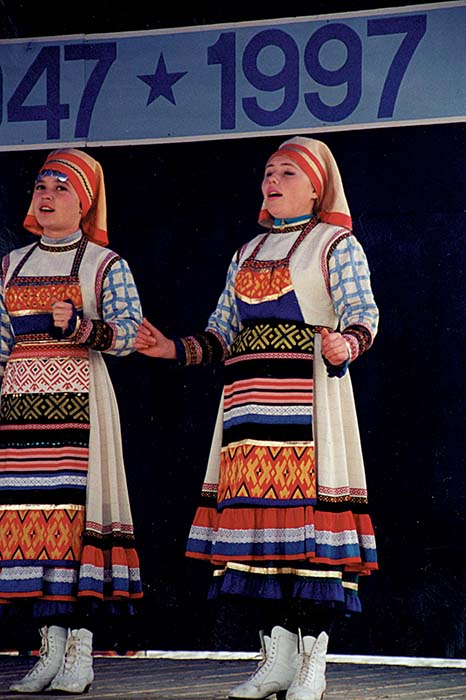

The ceremonies began with a blessing by the bishop dressed for the occasion on the steps of the main basilica in Izhevsk. He blessed the workers and especially the heads of government, and Kalashnikov. Because this was a celebration of the weapon and the factory where it was made the world renowned designer received congratulations and thanks from local and federal government representatives. However, celebration of the workers at the factories and their contributions over the years were given the same respect as those who had achieved individual greatness. One celebration followed a format similar to the old “This Is Your Life” program. We saw families representing three generations that had worked in the weapons factory. Staff read their own poetry and told stories of their lives and work at the factory. A play told the story of the founding of the original factory in 1807, and its effects on the little town and its inhabitants. On every occasion local dance troops performed in traditional costumes from the various parts of Urdmurtia. In many cases the performers were factory workers who studied local dance and folklore in their free time. All the speeches and toasts and performances made it clear that the weapons factories of Izhevsk are a center of the town’s history and commercial activities.

Among the many senior political leaders attending, Prime Minister Victor Chernomyrdin said in his speech during the formal ceremonies that economic reform was on the right track but also said factories cannot do it alone. According to Chernomyrdin and others, while privatization is the goal the Russian arms industry needs the government’s continued support. There were repeated references in official speeches to Russia’s international reputation being based in the quality of its weapons. The emphasis was on their intention to capitalize on that reputation emphasizing the defensive nature of their weapons. Several speakers referred to Kalashnikov’s weapons as “weapons of peace,” or “defensive weapons.”

The Prime Minister also said the Russian army needs new weapons, that they need to be resupplied and their inventories updated. He may have been referring to a decision made during the celebration to support procurement of the new 5.45 x 39mm AN-94 assault rifle. According to one source the Russian government has ordered production of a lot of 100 Abakan (AN-94) assault rifles for troop trials, with an additional order for 1,000 more for further tests. This still leaves unanswered the question of the feasibility of shifting to a complex, untried weapon system during a time of economic and political uncertainty. As Kalashnikov said in one of his speeches, “complex things are not needed, what is needed is simple…. All great things are simple.”

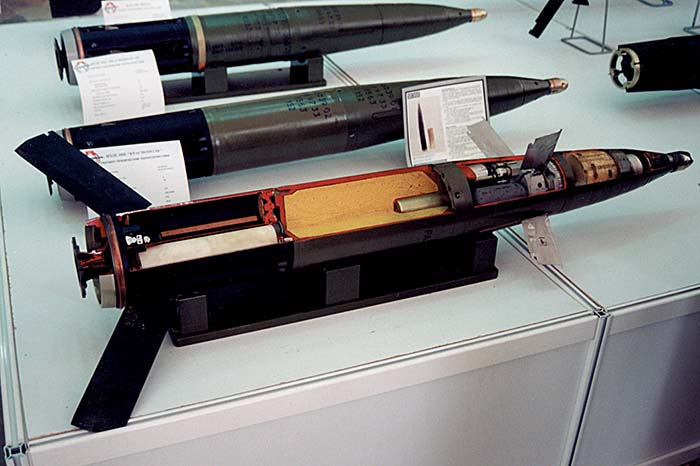

Over the next days various celebrations were held at several venues throughout the city: the Opera House, the City Theater, at the front gates of the old factory. Under the old Soviet system, IZHMASH was a complex of factories spread throughout the city. There was an open house and exhibition held at IZHMASH’s car factory, which we learned, was the site of the first production line of the AK47. They made the weapons there while the full production line was being set up at the IZHMASH weapons factory. The exhibition displayed the wide array of weapons, including prototypes, and other equipment made in some part of the IZHMASH complex. One subsidiary makes avionics equipment for surface to ground missiles. Another factory makes the guidance systems for the missiles, and another makes the missiles. They have a factory that makes electronic equipment for Russia’s space program. They also make hospital equipment, telecommunications switching equipment and night vision devices. In addition to making cars, one of the factories makes motorcycles.

In his speech Chernomyrdin said production was up 29 percent at IZHMASH, evidence that the strategy for development is showing results of the transition [to a market economy]. Economic reform at IZHMASH has meant splitting off of those various parts of the company – the auto manufacturing plant; rocket making facilities; holster factory; and others. They are now somewhat on their own to sink or swim in the new Russia currently organized as government-private joint stock companies. Company representatives at one of the factories admitted they continue to rely on the central government as their primary customer, but said their plans are to ultimately become entirely privately owned. They said their company which makes telecommunications equipment, among other things, recently signed a cooperative agreement to make switching equipment with Siemans of Germany. In every case, IZHMASH Joint Stock Company has preserved it’s position as the super structure of the corporation acting as a holding company of all of it’s former parts. In this way, it retains the ability to collaborate and transfer technology between the various design bureaus of all of the factories.

Some of IZHMASH’s competitors from Klimovsk and Tula also presented some of their work at the exhibition. There were holster makers, ammunition manufacturers, and enterprising artisans displaying specialty items such as one-of-a-kind hunting knives and colorful hand painted wooden presentation targets.

Masami and I spent time among the exhibits, Carlos Davila and Bob Stutler were giving interviews to the Russian media and meeting with government representatives. The presence of the two men coming from major American firearms makers meant potential new jobs to the Russian gun industry. The Russians were looking for their guests’ insight on the firearms market. They also were aware of the months of negotiations which Carlos, representing Smith & Wesson, was now in the process of firming up with the director general of IZHMASH. The agreement they reached during the days of the celebration would lead to a collaborative arrangement in which the two companies would be selling the other’s products. Smith & Wesson would try to sell IZHMASH’s submachine gun, the Bizon, and some versions of the Saiga shotgun in S&W’s police markets, while IZHMASH would assemble and sell S & W products in Russia. The Bizon comes in several calibers: 9 x 18mm; 9 x 19mm Luger; 9 x 17mm (.380 ACP); and a new caliber for this weapon, 7.62 x 25 TT. The latest caliber was adopted to defeat current Russian body armor.

While there appears to be a developing rivalry between the two factories, their labor and output had been clearly divided between long guns made at IZHMASH and handguns, submachine guns and various types of shotguns made by IZHMECH. The latter was established during World War II with machine tooling from Tula. Today they make the Makarov pistol in various calibers as well as specialty hunting rifles. IZHMECH also makes the Klin submachine gun designed by Mikhail Dragunov. The rather unassuming Mikhail would only take credit for completing a design he said his father had begun before his death.

The intense competition between the two arms makers of Izhevsk was evident during the celebrations. Given the intentions of IZHMASH to broaden it’s market share of the law enforcement and personal protection market, the intensity of this rivalry is bound to increase as the international outlet for their weapons production shrinks. The recent S&W/IZHMASH agreement to sell S&W products in Russia appears to be oriented toward the law enforcement market. It can take up to five years for an individual to receive a permit for a handgun, but perhaps as little as one month for a permit to own a shotgun. In addition, Russian laws are more lax regarding gun barrel length. Shotguns restricted to law enforcement sales in the United States can be legally owned by private citizens. According to a company spokesman it is IZHMASH’s intentions to promote shotgun ownership in Russia in the home protection market.

It seemed apparent during our visit that both IZHMECH and IZHMASH are going after their domestic market, which is clearly a source of the increased rivalry between the two companies. A representative from IZHMECH said that his company was not as concerned about the U.S. market at this time convinced the Clinton administration’s arms import bans against nearly every Russian firearm are designed to protect American gun makers. While determined to get the money owed them from U.S. companies who have taken deliveries without paying, IZHMECH representatives said the company will continue to market in the United States but rely on sales to other countries and in Russia.

IZHMECH also hopes to recoup money from the government of Estonia it says the country owes for weapons confiscated in 1992. At that time a quantity of IZH-70 pistols in transit to the United Kingdom were confiscated by Estonian customs in Tallin, Estonia. IZHMECH sued the Estonian government. After appeals the courts decided in IZHMECH’s favor but the Estonians have so far failed to comply with court orders to compensate IZHMECH. The company has asked its Member of Parliament to appeal to President Boris Yeltsin to speak to the Estonian government on its behalf. Hearings in the Urdmurtian parliament have been scheduled. Meanwhile IZHMECH hopes to win over world public opinion to pressure Estonia to pay up; an effort some say will be an uphill battle given Russia’s reputation in it’s treatment of Estonia under the Soviet regime.

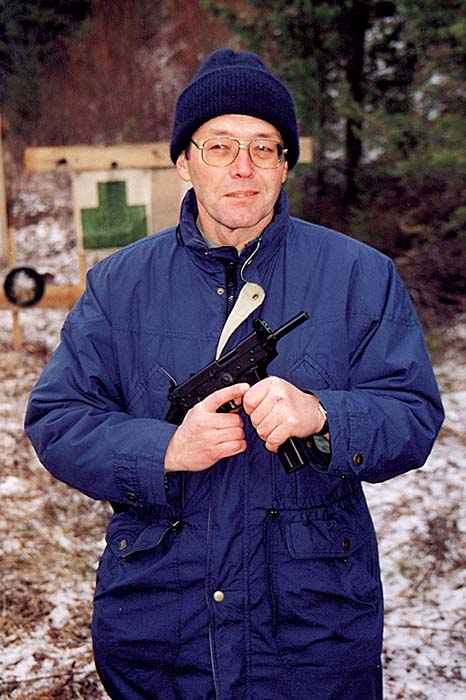

In addition to the exhibitions and speeches, we were given the rare opportunity to go out into the countryside to fire some of the products from the IZHMASH and IZHMECH factories.

At the range, Masami, Carlos and I had the whole array of weapons from both factories from which to choose: everything from Saiga shotguns in various configurations, to new variants of the Makarov pistol. IZHMASH picked us up at our hotel. When we arrived we found the range overrun with many other visitors, as well as members of the Russian media. We also were there to cover the events of the four-day celebration but for me this was a rare opportunity. I chose the Bizon submachine gun which we had heard so much about over the past several months. Not having much experience shooting submachine guns, I was ready for the usual recoil and subsequent climb I usually get when I fire something on full auto. With the buttstock tucked as snuggly as I could get it into my shoulder and leaning slightly forward with knees bent into the weapon, the way some friends at Heckler & Koch had taught me, I aimed at the target and pulled the trigger. To my surprise the Bizon had no recoil! In response to my exclamations, Victor Kalashnikov, Mikhail’s son and one of the weapon’s two designers, admitted that they had dubbed it the “women’s gun.”

The new AN-94, the Abakan, also was on the firing line for people to try. The weapon’s designer, Gennadiy Nikonov, had been a guest of the Institute the year before. His unusual weapon has a variable rate of fire, dropping from an approximate 1800 rounds per minute rate after the first trigger pull to a more routine 600 rounds per minute rate. (See SAR Vol. 1 No. 6) Having seen the pictures and heard the lectures, Masami and I both wanted to fire it. When it seemed that it might be our turn, we were disappointed to find out that they had just run out of ammunition. So Masami went down the line to fire IZHMECH’s new Makarov and the Klin.

By the time we left we had a greater appreciation for the weapons and the people who had designed them. It was an especially cold, gray day. Of the four of us only Carlos seemed comfortable. He was smart enough to bring along the bearskin hat he bought on one of his earlier visits to Red Square in Moscow. The cement floor of the firing line was so cold that it seemed to radiate up through our boots to freeze our bones right up to the knees.

Throughout the several days in Izhevsk we had the privilege of meeting with Kalashnikov, either at his home, before or after the ceremonies, or at dinner at “The Bear,” one of Izhevsk’s fancy new private dinner clubs. On every occasion he impressed us with his vigor and his humanity. We traded stories about each other’s grand children. He gave advice and encouragement to me on our work at the Small Arms Research Institute Ed Ezell had started before his untimely death in 1993. He recognized Ed and Masami for the books they had written about Kalashnikov and his weapons. In his Old World style, he welcomed us into his home and made us feel a part of the family.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V1N7 (April 1998) |