By Gabriel Coutinho de Gusmão

(This is a multi-part series. Click here to read Part I.)

In the last chapter of this story, we talked about the conversions patented and made during the interwar period. The United States had set out requirements for a new semi-automatic rifle, one of them being to re-use as much tooling from the M1903 Springfield as possible. Brand new nations rose up after the end of the first world war, like Czechoslovakia and Poland, who had to scavenge as much equipment their former overlords had left behind while trying to keep up technologically with the other great powers, leading them into the “conversion” route. Italy followed a similar route as the United States, having interchangeability/ease of manufacture in mind.

With the ascension of Germany and the threat of war looming again, some countries resorted to drastic measures to arm themselves. By the start of WWII, semi-automatic rifles had progressed to a point where they were viewed viable as an army’s standard issue rifle, like the M1 Garand. However, their importance was neglected by other nations like the United Kingdom, who, even though ran many trials throughout the interwar period, failed to adopt a semi-automatic rifle in time for the Second World War.

Others tried to capitalize on this issue, companies like A/B Snabb marketed a way to convert “obsolete” bolt-action rifles into semi-automatic ones for a fraction of the price. Though an attractive proposal, these usually came with a few caveats. Most conversions, however, came from private inventors trying to help their countries in such a time of need.

THE SUN NEVER SETS

The Commonwealth had a rough start in the Second World War. Despite many trials conducted in the inter-war period, they never settled on adopting any kind of semi-automatic rifle or submachinegun, finding them superfluous. With Germany’s Blitzkrieg catching the British by surprise in Dunkirk, the advances made in Africa and the Japanese threat in the Pacific, it was realized that there was a need for desperate modernization of small-arms in the Commonwealth forces.

The most successful attempt out of all of the conversions submitted was the Charlton Automatic Rifle. In fact, it is quite likely the most successful conversion ever made. This system was the brainchild of inventor Philip Charlton, who noticed his country’s dire situation when Japan declared war while most ANZAC troops were fighting on the North African front. The rifle was tested and passed with flying colors, which was followed by an order of converting 1,500 rifles, mostly obsolete MLEs and Lee-Metfords left over from the Boer war.

The Charlton operated very similarly to other Lee-Enfield conversions, with a gas-tube being precariously attached to the right side of the gun. However, the New Zealand model was unique in a sense, since it was one of the few conversions that allowed for fully automatic fire. The other Charlton manufactured in Australia was a more conventional rifle, having most of the inner workings covered up and being semi-automatic only.

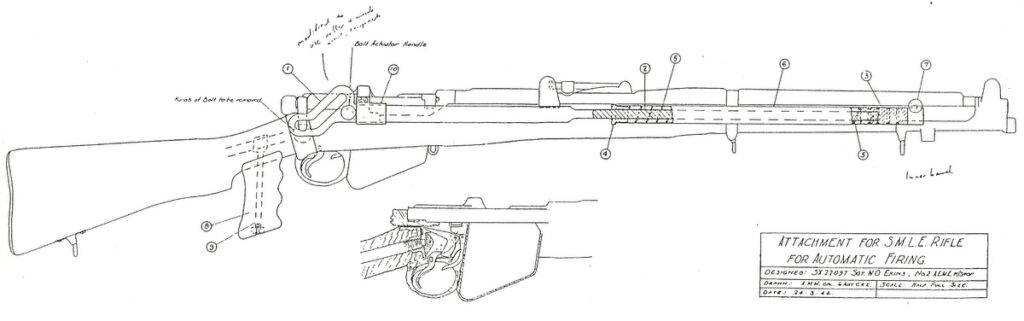

Another less well-known rifle from the Oceanic colonies was the Ekins, however there is no evidence that his rifle went farther than a surviving draft dated to 1944.

The Rieder was another proposal from the colonies, this time from South Africa. Henry Rieder, who tinkered with radios and televisions, proposed a simple conversion of the SMLE to the South African authorities in early 1940. 18 rifles were then modified, and some were sent to England for formal trials. It seems that by 1944 with the war almost at an end in Europe the Rieder rifle was finally set aside, with a single rifle being returned to Rieder on behalf of the Admiralty.

Also from South Africa, the curious Howard-Francis carbine, chambered in 7.63x25mm Mauser. It was shortly trialed by the Ordnance Board in London where it failed to meet even the most basic expectations. The feed system malfunctioned, had to be manually fed every shot, and the rifle was noted to have extremely poor accuracy. The Ordnance Board concluded that there was no point in any further interest due to its poor results in the tests. Information about other submissions from the Empire are, unfortunately, hard to come by. Included is the Brown machine-pistol adapter for the No.1 and No.4 rifles, apparently it was very similar to the American Pedersen device of the First World War.

Designs from other countries were also considered. Rehnberg and his company offered to convert an SMLE to the SNABB system, which as far as the author knows was never undertaken. The other was the Scotti system being applied to a P14 Enfield rifle, which was completed and sent to the British for testing before the start of the Second World War. The rifle had a rough start, as when it arrived from Italy, some parts were already broken off and certain accouterments requested for testing were not present, such as spare barrels. Nevertheless, the British continued trials of this rifle until 1941 when it was finally deemed unacceptable. Meanwhile in Canada, a curious SMLE conversion by the American Russel Turner was being tested against the M1 Garand. Unfortunately, even though in some aspects it performed better than its competitor, it still lost out because it was deemed too complex.

MISCELLANEOUS COUNTRIES & CONVERSIONS

By the time the Second World War started, most countries had already written out conversions as a possibility, instead opting for brand new semi-automatic rifles, like the SVT-40 in Russia, the M1 Garand in the United States, and the G41/43 rifles in Germany. Despite this, some minor nations still considered the idea viable. As I couldn’t locate many from a single country like I’ve done in prior entries in this series, this part is going to be an amalgamation of what I was able to identify.

In Greece, we have the Rigopoulos conversion. Being tested shortly before the German invasion of the mainland, it was apparently approved for adoption and requests were sent for its production. Despite this, the author has not been able to identify much information about this rifle.

In Russia, at least two conversions were tested before the adoption of the SVT-40; these are the Mamontov and the Goryainov. Both worked in a very peculiar way, by utilizing the slight movement of a cartridge between the bolt face and the chamber, comparable to earlier attempts by Georg Roth and Garand of making primer-actuated rifles.

In Sweden, during trials to adopt the Ljungman self-loading rifle, an inventor named Erik Wallberg submitted a few designs for converting the Swedish Mauser to be semi-automatic. They all utilized a simple gas piston. Wallberg would go on to build SLRs from the ground up instead of conversions using the same principle.

And finally, China. In 1944, engineers named Wen Chengding, Wu, and Liu developed an automatic rifle based on the Arisaka by simply attaching a gas-piston to the left side of the gun. It seems that the rifle was tested against a M1 Carbine, which the designers remarked that their rifle had a better muzzle velocity and range.