By Ted Dentay

It didn’t look like much until it cost 9,777 U.S. Marine casualties over just a couple of months that summer of 1918. They were the worst losses ever experienced by the Marine Corps up to that time. It was a hell of a European baptism of fire, especially after earlier actions in the Spanish-American War days like Nicaragua and Cuba. But American Expeditionary Force (AEF) troops had never experienced killing on such an industrial scale, as the European theater was described after World War I. They were fighting against seasoned German troops, fresh from years of combat on the Russian Front, that had been released to ‘take ‘em on’ that summer. French troops, exhausted after four years of incessant combat, were in support. Unlimited artillery ammunition was available to the enemy. German 7.7s (77mm) in particular, fired from latest Krupp FK 96s, devastated them, the equivalent of British 18-pounders fired by the tens of millions a little further northwest in Flanders’ trench war…the “Western Front”.

Marines were hastily equipped before being shipped off from the continental United States. They toted their rifles, .30-06 caliber ’03 Springfields and P-17 Enfields with them (the latter made by Winchester, Remington Arms and the Eddystone Arsenal) with new-issue ’06 ammo stashed and issued quickly from quartermaster stores. Some of the ammo was modified from .30-03 stocks

the original caliber that predated the ’06, of which eight million rounds were modified by Frankford Arsenals to the new 2.479-‘06 case. Those new ‘06s, stoked with Hercules smokeless powder, propelled their 150-grain stannic-stained, cupro-nickel jacketed bullets from the muzzle at 2,750 feet per second.

Light machine guns (LMGs), usually restricted to French “Chauchat” C.S.R.G. machine rifles, originally chambered for the French 8mm Lebel but, later, rechambered to the American .30-06. Perhaps there was the odd M1917 Browning watercooled medium machine gun (MMG). More commonly the Hotchkiss (Benet-Mercie) LMG, probably the last model that was good enough to remain in service until after World War II, despite the fact that the 1918 B.A.R. (Browning Automatic Rifle) had been developed at the time but was not an issue item then.

Unbeknownst to me at the time, “follow the bullet” was the word of the day as I got to Belleau Wood in July 2018 after having previously spent time down south in the relatively unknown Vosges Mountains battlefield of Hartmannswillerkopf.

The impeccably maintained Aisne-Marne American Cemetery with its marble gravestones, the redolence of thousands of pink roses, and the echoing chapel at the top of the hill. A deeply moving place. But the forest behind the cemetery beckoned.

Researching U.S. involvement in World War I is a sketchy business because politics sticks its nose into everything. America often claimed a role that other combatants of the time contested, claiming the U.S. had hardly entered that war before it concluded on November 11th, 1918. Regardless, the actions of U.S. troops at that time were brave beyond measure. The problem for me was trying to imagine what happened in Belleau Wood during those days of summer, 1918.

I asked the French cemetery maintenance staff where the actual battle area was and they pointed me to a narrow-paved lane to the east, its grassy verge lined with red poppies. Immediately north of the memorial chapel, and with no-one apparently caring, I went up in the rental car, my metal detector and shovel in hand. What I found told a forensic story.

Belleau Wood today is administered by XXXX (details to follow). They do not encourage visitors to explore the one-mile by one-mile now-heavily-treed battlefield. [PULL THE RED HIGHLIGHTED PASSAGE IF WRITER CAN’T AMMEND/CONFIRM-RC] A flimsy wire fence surrounds the southern boundary, close by where French farmers dump rotting bales of hay and produce. But there is an unlocked gate and no sign forbidding entry.

The forest resounds with birdsong today. The rocks and topography are much the same as they must have been more than 90 years ago. Remnants of slit trenches wander beneath the fallen leaves. Not the deep trenches as in Flanders, but the type of crawl trench that would keep your ass from being shot off if you kept your buttocks low.

Two grayed rocks poked above the forest floor a few hundred yards north of the gate through which I passed. I looked at them, looked out over the field to the northeast where I figured the Germans must have attacked from, then tried to work out their tactical situation of the time. Deploying my detector I looked in front of the rocks and found what, from my point of view a century later, told a story.

Just ahead of the crevice of the large rocks, which I too would have chosen as cover for my LMG, was a small pile of empty cases and a live one: an 8mm Lebel. To the right were some corroded .30-06 empties and a couple of empty five-round brass stripper clips.

To the left were some corroded empties plus a partial stripper clip of unfired .30-06 rounds. Casting about behind the rock and the trench behind it, I found a partially exploded artillery shell about 15 feet away. Here’s my interpretation of what happened during those moments of that day. It’s a guess made on the evidence I found:

I wondered about the presence of 8mm Lebel ammo there since I knew the French weren’t present. It was likely a U.S. Marine Hotchkiss position, the whole business of light machine guns with U.S. forces being a complete story unto itself.

Flanking the Marine MG gunner and his loader must have been a couple of riflemen. When the Germans attacked the action was deadly. The M1914 Hotchkiss, one of 7,000 purchased by the U.S. from the French, chattered until there was a stoppage. The gunner cleared the jam, extracting the chambered round where it dropped onto the ground amongst the empties, and kept on smoking at 500 rounds per minute. On either side his flankers were firing their bolt guns as fast as they could. The right-hand guy was whaling away effectively, making every round count. Grabbing clip after clip from his webbing and reloading his now-hot rifle. The Germans’ nightmare of Marine “Devil Dogs” and their accurate fire coming true. General John “Blackjack” Pershing, commander of the AEF, was quoted as saying, “The deadliest weapon in the world is a Marine and his rifle!” He is also quoted by various sources as having said, “…the Battle of Belleau Wood was for the U.S. the biggest battle since Appomattox and the most considerable engagement American troops had ever had with a foreign enemy.”

The left-hand flanking rifleman wasn’t as certain. He must have tried to reload in the heat of combat, fumbling and dropping a full five round clip onto the ground. Maybe he was distracted by the muffled explosion of something hitting the ground just behind him: a German 7.7cm artillery round that failed to completely detonate (see the sidebar.) He did manage to send off many 150-grain cupro-nickel deadly messages to the Germans before this happened, judging by the corroded empties near his position. We’ll never know for sure.

What we do know is where and when the rifle ammo was made, by whom, and how it reflects more than just ammunition: it is an indirect record of how well U.S. supply lines worked, reaching from the shores of the continental United States to a battered forest in northeastern France, and contains some interesting clues on the development of the .30-06 Springfield round.

Incidentally, the artillery round that almost killed the Marines manning that Hotchkiss position also provides an equally interesting sidenote into artillery use during World War I.

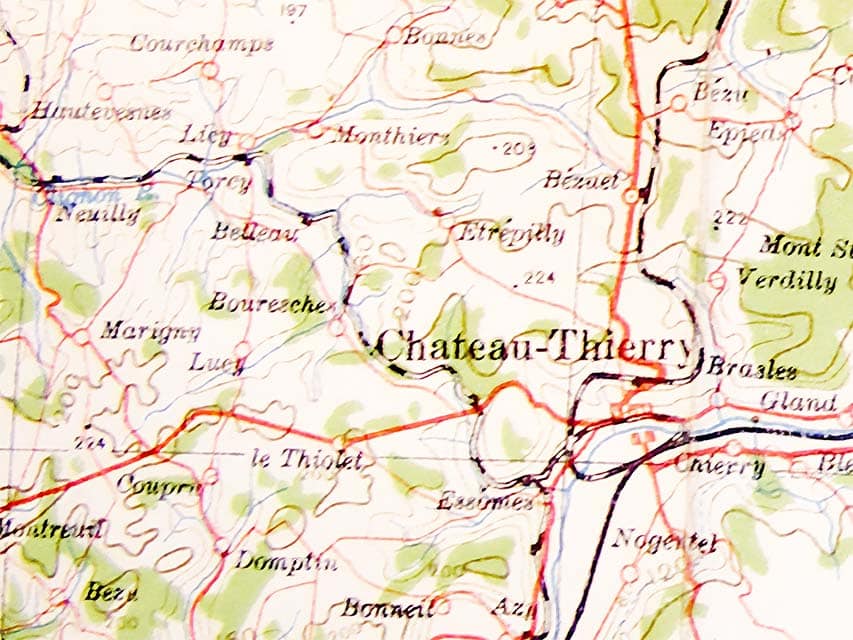

About 100 miles east of Belleau Wood and Chateau Thierry is the 1916 slaughterhouse that was Verdun and the fortress of Douamont. One of the most inexplicable and bizarre ammunition finds I ever made was found in a stretch of forest a few kilometers southeast of the fortress itself. Under the loamy duff, I found a section of steel plate that had been blasted by artillery fragments, had a bullet hole, and was dimpled by something else. Nearby was a French 8mm Lebel cartridge that seemed to be empty at first blush and had a crack on the case that looked like water had frozen inside, expanded, and split the case. When I shook it there seemed to be something inside the case, mud, or sand I thought, until I gave it a vigorous shake. Out came the base of a bullet.

Since I had personally dug it up, I knew that there had been no substitution. This was how the thing had been made! But “why” is a question I’ve not been able to answer. The closest guess is hearkening back to the introduction of the first tanks during World War I…but that was at Cambrai in 1917, which was a year after Douamont had fallen. At that time the Germans found their 8x57mm bullet, which would glance off the primitive armor of the time more often than not, would penetrate the armor if the bullet was reversed in the case. So why this?

The 8x50R Lebel has some interesting design characteristics that I only discovered after having observed different base designs on the various cartridges I found on battlefields across Europe where French forces had been involved. One of the major design differences is a large annular ring around the primer. Some samples didn’t have that ring.

Turns out that the French had a unique solution to deal with using their then-new spitzer (pointed) bullets in the eight-round tubular magazine of their Mle 1886 M93 (Lebel) rifle. The point of one bullet wouldn’t touch the primer of the round ahead of it because it was guided onto the annular ring so accidental ignition from the rifle’s recoil was significantly reduced. These rounds were usually base-stamped “D a.m.” which stood for the Balle D. bullet and a modified primer.

The Balle D bullet, in conjunction with the 8x50R cartridge, was a major milestone in small arms ammunition that involved both French and Swiss technical advances at the time.

It was the first rifle round to use smokeless (nitrocellulose) propellant, Poudre B, developed by French chemist Paul Vielle in 1884, and to use a spitzer, or pointed, boat-tailed bullet. Although the gracefully designed 197-grain Balle D was solid bronze, it sprang from Swiss Capt. Eduard Rubin’s (a partner in the design of the Swiss straight-pull action Schmidt-Rubin rifle) development of the cupronickel-jacketed, lead-cored, full metal jacket bullet that has been the defactostandard in small arms projectiles ever since. The French use of smokeless powder and the new bullet tripled the power and effective range of a small arms round over the former black powder cartridges of the time. The claimed maximum extreme range for the Balle D was claimed to have been 4,000 yards; the maximum wounding range 1,800 yards, and a realistic effective range of 457 yards. The round had a muzzle velocity of just over 2,100 feet per second with a remaining velocity of about 750 feet per second at 2,250 yards.

About 300 miles southwest of Belleau Wood, where Germany, France, and Switzerland meet, about an hour south of Strasbourg, France, is the little-known battlefield of Hartmannswillerkopf. At 4,500 feet and the highest peak of the Vosges Mountains, it was the site of interminable struggles through the whole 1914 – 1918 period that involved almost all the European powers drawn into the conflict, even the Swiss. Over the years I have found some technically and historically fascinating ammunition and other materiel that would paint a picture of what happened there. Another example of “follow the bullet.”

Riddled with tunnels and concrete bunkers, the original forest blasted to matchwood at one time, the rugged area is again heavily forested today. You could easily imagine how difficult it must have been — all while under intense fire — for the individual soldier to get around, much less keep the troops supplied. I heard from Alsatian locals that between 1914 and 1918 almost seven meters (22 feet) was blasted off the entire mountaintop by the millions of artillery shells fired at it.

Shallow slit trenches, paralleling the rugged contours of the mountainside almost like terraces, still exist and tend to lead to the more complex fortifications perforating the mountain. The combatants had four years in which to consolidate the many positions, which regularly changed hands, so it was always a guessing game to find still existing redoubts that were still relatively safe to explore. (Deep trenches, such as those found in Flanders’ salients, were difficult to dig in Hartmannswillerkopf because of the crenellated topography and rocky substrate.) I wouldn’t have wanted to attack uphill there where dozens of grenades could simply be rolled down on top of you by the defenders.

Because of the well-drained and relatively dry rocky soil, unlike the wet blue clay underlying Flanders, artifacts such as barbed wire, small arms ammunition, explosive ordnance, and other materiel remains quite well preserved. The classic World War I 12-barbs-to-the-foot barbed wire, which has crumbled to red dust pretty well everywhere else, still remains effective there, even a hundred years later, as my jeans can attest!

The 8x50mm Lebel cartridge as found

When I first started exploring World War I battlefields in 1971, I made an interesting find in one of the tunnels. Just inside the entrance I found the remains of a cardboard box partly filled with 8x50Rmm Lebel ammunition. Later, at home in Germany, on pulling the 197-grain bronze Balle D bullets, I found the case to be filled with fine sand, which I thought was the result of water and silt infiltration. Later I learned that, well into World War I, the French knew they were losing. At least one ammunition manufacturer lined its corporate coffers by substituting powder with sand, theorizing the ammunition would never be fired anyway. I understand from reading the history of the time that those responsible were eventually executed by the French for treason.

Other unique discoveries included an odd spent bullet; a nearby lead core; something that looked like an overgrown “jumping jack”, and a grenade of some sort.

The flat-based bullet miked out at 7mm (.284-inch), which was unusual since everyone was using a fairly distinctive 8mm bullet in their small arms at the time. My best guess is that someone (probably German) was using a gun chambered for the 7x57mm cartridge and rifled with a five grooved right-hand twist. A more comprehensive examination could probably tell you the specific gun it was fired from.

The jumping jack was a caltrop, a small multipronged steel spike that, however thrown, would always land with a point upwards. It was originally intended to be used as an area denial device against cavalry horses and could possibly have been intended to deter horses used to haul artillery and supply wagons on this battlefield. (Quite possibly the last time in the history of warfare that the caltrop was used.)

The grenade was shaped like a lemon and had the remains of a wooden plug at its mouth. A rotted length of safety fuse and a perforated blasting cap was in its interior. Otherwise, it was free from explosive. Just full of mud and one juicy worm. As its shape would indicate, this was an example of the French “Citron” grenade. I had visions of a French trooper, glowing Gauloise cigarette butt in hand, trying to light the fuse. I’m unsure of how they were initiated since this model is a very early one.

About 400 miles (670 kilometers) due north of Hartmannswillerkopf are the well-known battlefields of Flanders, Belgium, Ypres being the most notable. Others included Passendaele and Poelkapelle. While America took a while to shuck their notion of isolationism, Canadians had been beavering away in many of the salient battles, the fields still rich with lead shrapnel balls, shell fragments, artillery fuses, unexploded ordnance (UXO), and the general litter of war.

Virtually every farm has an “Obus” pile: a stack of UXO of every description which are regularly carted away by a Belgian armed forces truck.

One strange experience I had early on in my battlefield explorations took place on the bank of the Yser Canal, near the village of St. Eloi in Belgium, within earshot of the cathedral bells in Ypres, and virtually a stone’s throw from one of the immense craters created by a huge underground mine explosion, part of the “Battle of the Craters”. The explosion was so immense that it had been heard many miles away in England.

My friend and I were having lunch one summer’s day and I was idly digging through the soil with my fingers. It didn’t take long before I found a couple of empty cartridges; an 8x57mm and a .303. A little bit lower down I found another couple of empties, again, 8x57mm and .303.

Curious as always about headstamp information I cleaned off the bases.

What I saw made me re-examine them more closely. The 8mm round had been manufactured by Germany in 1943. The .303 had been manufactured in 1941 and also featured the Mk.VII stamp, which denoted the propellant type. More strangely from the evidence, the 8×57 round had unmistakably been fired from an MG-42 machine gun and the .303 round from a Bren light machine gun. The MG-42 characteristically mangles the case mouth on ejection from the gun for a few reasons: one being that the ejection port is on the bottom of the receiver. Another being that the roller-locked action is assisted by a muzzle booster which taps powder gases in order to give a greater impulse to the action and which contributes to the phenomenally high fire rate of 1,200 rounds per minute of this stamped-steel gun. This violence of operation left a characteristic imprint on one of the empties. The Bren has an elliptical firing pin imprint. Remember: we were sitting on a World War I battlefield.

The other two empties? They had been manufactured variously between 1914 and 1916. German and Allied troops had fought over the same ground, decades later, showing that no lessons were learned in the interim.

Overall, it’s interesting how a modicum of gun knowledge can reveal long gone worlds of conflict, much like reading a book can. Ammunition is the tell-all if you can speak the language. All you have to do is “follow the bullet”. As for explosive ordnance? Well, if it didn’t go off when it was intended to, then it wasn’t just dropped in the heat of combat and still remains as deadly as when it was first made.

Finally? By sheer dint of tenacity, bravery, and timing, Belleau Wood ultimately became an American victory. Semper Fi, guys. Semper Fidelis.

The German UXO 7.7

This shell led me on a merry chase. At first, I measured it as a “75”, which was the standard caliber of the then-famous 75mm French artillery piece. But the French couldn’t have been firing on the Americans in Belleau Wood since they were allies.

With rust and mud on the round from having been buried for almost a century I could be forgiven for my error. It was a heavy piece of ordnance. From later research I found it to be the equivalent of the British 18-Pounder, but without the lead shrapnel balls used further northwest in Flanders to get at the deep trenches of that area of operations, although the shell did have a shrapnel-ball variant along with poison gas and a primitive, direct-fire antitank round.

Concerned about explosive content before bringing the spent round home to Canada with me, I cleaned it out and found that, indeed, there was still some explosive material left in it. The neutron backscatter explosives sniffers at Montreal’s Trudeau airport reported the traces of 100-year-old explosive. Terrorists beware!

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V26N4 (April 2022) |