By Alton Chiu

Close Quarters Battle (CQB), also known as room clearing, is a demanding endeavor that even ordinary citizens may find themselves doing. If we come home to an open door and screaming family, waiting for help is not an option. If we suspect a home invasion, shelter-in-place is insufficient if we need to gather and secure other family members. In such cases, we prefer not to tackle this difficult and dangerous problem without prior experience.

Orion Training Group (OTG) fills this need with open enrolment courses. We first attended an introductory class focusing on solo and duo-response. We honed fundamentals like footwork, then learned to navigate complex room geometries and the use of additional manpower for speed and security. We attended another night vision CQB class. Using fundamentals from introductory course, we dealt with light gradients while learning the limitations of technology first-hand.

OTG imparted knowledge in digestible chunks, introduced multiple methods to solve the same problem, and held students accountable for their choices (or lack thereof) when they outrun their brain. Force-on-force tested our execution. The teaching points were not focused on any citizen, law enforcement, or military context but rather emphasized how resources, mission, and environment dictated tactics. Throughout these courses, we had to consciously slow our movement down to our processing speed in order to make optimal decisions; more than once, we played the fools who rushed in where angels feared to tread.

SPATIAL AWARENESS

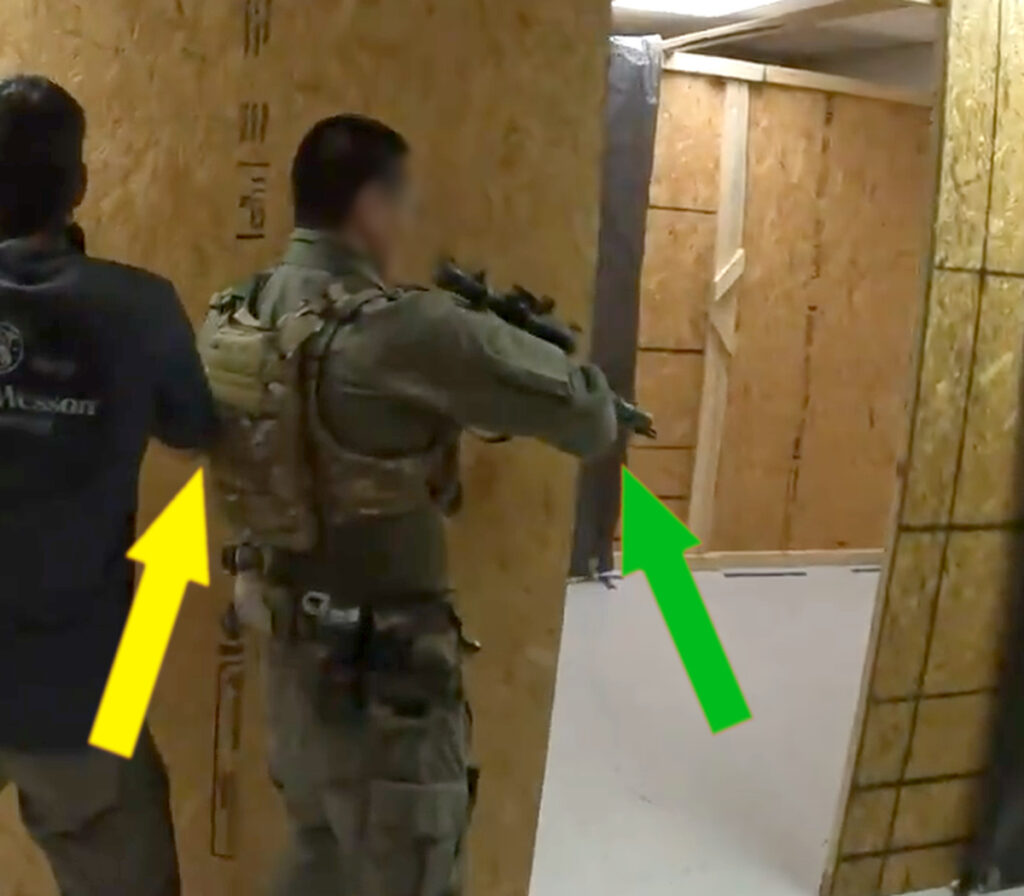

CQB is a game of angles. Before we can process and address the angle with our eyes and weapon, we must avoid overexposing and telegraphing our location. We could procedurally short-stock a rifle over or under our shoulder (see this YouTube video, but we should recognize our environment and decide whether it is necessary or desirable. With wide hallways common in commercial buildings, it is possible to pan a door with a shouldered rifle without extending its muzzle past the threshold. There may even be sufficient room for another teammate to hold hallway security while panning. However, environmental features (such as opposing doors) may dictate a simultaneous pan where it is necessary to short-stock our rifles. During force-on-force, we needlessly compressed our pistol to pan a threshold because we always procedurally short-stock the rifle. This left us unable to return aimed fire when confronted during the pan; we could only run away like Monty Python and the Holy Grail. During this scenario, we failed to recognize and exploit the fact that a pistol reduces overexposure concerns.

We also learned our habit of leading with our elbow when pieing around a corner. With a heavy rifle, we chicken-winged to manage the weight. With a pistol, we formed an isosceles stance. Both caused our elbow to telegraph our location long before our eyes can process the scene, make decisions, and apply ballistic counselling.

We observed other students ducking back behind a corner due to incoming fire, only to re-peek at the same height when opposition is ready and waiting. Force-on-force punished these mistakes and reinforced the demand for spatial awareness that can only result from slowing down to our processing speed. Outrunning our processors inevitably lead to failures.

LIGHT MANAGEMENT

We intuitively understand we should minimize light emissions to maximize surprise, but we also learned to broadcast light to our advantage. If we were already backlit (i.e., already compromised), we can create a photonic barrier with our weapon lights and deny information. The opposition can neither discern our manpower, nor choose a point-of-aim. Of course, we must process the environment to judiciously use this at the cost of surprise.

Light can also be used to disrupt the opposition’s observe-orient-decide-act cycle (aka “OODA” loop) and somewhat increase the violence of action when distraction devices are unavailable. Modern weapon lights with 1000+ lumens can be blinding and might cause recipients to involuntarily squint or raise their hands to block the light, thus disrupting their firing solution. We experienced this during force-on-force. In another scenario, we lost speed while pieing a corner under night vision. Intuiting the bad guy is in the room, we employed white light during entry to increase the violence of action and regain the initiative.

On the more subtle side, we recognized environmental lighting gradients that dictate our entry method. Stacked strong side in a bright hallway and about to enter a dark room, we could have moved across to create a split stack and to better manipulate the door or perform a crisscross entry. However, this would cast our shadows under the closed door and telegraph our location. Mindful of this limitation, we chose to enter strong-side to maintain surprise. In order to make informed decisions, our legs must not outrun our brain.

COMMUNICATIONS

To non-verbally communicate with teammates, instructors emphasized consistency across different lighting conditions. For example, one can muzzle pump or wag to ask a teammate to open the gate for a safe entry. We chose to wag regardless of lighting conditions because one cannot easily discern a pump under night vision by just observing the pointer. The limited field-of-view also forced us to constantly scan for these signals. Moving too fast caused us to miss cues, which created chaos.

Slowing down to process our teammates’ body language made us smoother. For example, a teammate’s intent focus behind a couch indicates a dead space. That prompted us to move and assist. Conversely, we learned to wait for others to process, else we risk launching into the next problem unsupported. This is especially important under night vision with degraded field-of-view, reduced contrast, and such.

Our instructor remarked that the hallmark of a good team is not the lack of mistakes, but the fact that gaps are recognized and plugged on-the-fly. We found we can only achieve that by processing cues. As the class progressed, repetitions improved processing speed. Consequently, movement speed increased, as well.

Every player of an effective sports team knows all plays and calls; every member of an effective CQB team knows all techniques and signals. A team that frequently trains together can establish default tactics techniques and procedures (TTPs) to increase efficiency and reduce confusion. For example, a teammate expecting a strong side entry while another expecting a crisscross can create a fatal foul-up. OTG took pains to present a plethora of techniques and encouraged students to explore, all without forcing their preferences upon us. While students agreed upon TTPs for the remainder of the course, instructors emphasized flexibility by requiring us to articulate our decisions. During a scenario, we found hostages but no hostage-taker during the initial threshold assessment. By processing our environment, we realized we dawdled too long and might be backlit by ambient lighting. Following TTP to pan over for crisscross entry would actually increase risk to both the hostages and the entry team as we lost surprise already. By making a strong side entry without delay, we increased speed to regain the initiative. We were successful because we processed environmental clues while our teammates processed our body language, obviating the need to verbally call for the play.

CONCLUSION

OTG provides open enrolment classes to tackle the difficult and dangerous problem of CQB. Instructors presented multiple techniques and emphasized flexibility while holding students accountable for their choices. We learned to move only as fast as our processing speed for spatial awareness, light management, and non-verbal communications with teammates would allow. Practicing micro drills at home improves individual elements, but we feel the needed to also practice with others for stimulus and communications. This, and the valuable critique from instructors, is why we find utility in repeating courses from time to time.