By Janne Pohjoispää, photos by Juha Rintala

In 1961, the Soviet Red Army took a major step in small-arms deployment by replacing the belt-fed 7.62x39mm RPD (Ruchnoy Pulemet Degtyareva) light machine gun with a magazine-fed RPK (Ruchnoy Pulemet Kalashnikova) LMG, also firing the 7.62mm M43 intermediate round. While the Soviets viewed this as a step forward, many small-arms authorities viewed this decision as a step backwards since the new weapon was neither as robust nor as well suited to delivering sustained fire as its predecessor. As its external appearance suggests, the RPK is a spin-off of the AKM assault rifle that is fitted with a heavier barrel and a light bipod. The first RPK prototypes were built on machined AK-47 receivers in the mid-1950s, but when the RPK went into production in 1961, the receiver was switched to the stamped AKM-pattern. The AKM had been adopted two years earlier, in 1959.

Designed by Mikhail Kalashnikov, the RPK appeared in public for the first time in the 1966 May Day parade in Moscow’s Red Square, but Western intelligence agencies were aware of its existence before then. Like most other small arms manufactured by the Soviet Union and its allies, the RPKs were distributed to many countries under Soviet influence as well as to communist insurgents conducting their so-called wars of liberation. RPKs have, therefore, seen action in most conflicts throughout Southeast Asia, Central America, the Middle East and Africa since the 1960s.

Thanks to the prolific distribution of Soviet small arms to friendly countries and groups, there are probably more RPKs around the world than any other magazine-fed LMG. The RPK and RPK-style guns were manufactured at least in China, Finland (Valmet LMG 76 and LMG 78), Iraq (Al-Quds), North Vietnam (TUL-1), and Rumania and Yugoslavia (M65, M72, M77, M82). Some of these weapons can be called RPK-style guns because they are based on a milled AK-47 receiver rather than on a stamped AKM receiver. Certain RPK variants are semiautomatic-only guns aimed at the civilian marketplace. Not all RPK variants were designed for the role of squad automatic weapon, however. The RPK has also served as the basis for several sniping rifles. Perhaps the best known RPK-based sniping rifle is the Rumanian FPK, which is chambered for the full-powered 7.62x54R round. Valmet also made a 7.62x51mm sniping variant of the LMG 78 for a short time. The Iraqis fielded a semiautomatic sniping variant of the Al-Quds chambered for the unsuitable 7.62x39mm M43 cartridge. The RPK family’s complete caliber selection includes chamberings in 5.56x45mm and 7.62x51mm for the Western marketplace.

While a fixed-stock RPK is the most commonly encountered variant, a folding stock version chambered for the 7.62mm M43 cartridge, called the RPKS, can also be encountered. In 1974, introduction of the AK-74 assault rifle chambered for the 5.45x39mm M74 cartridge was followed by the introduction of a 5.45x39mm light machine gun, the RPK-74, and a folding stock variant, the RPKS-74.

At this point, one might wonder if the RPK or any other weapon of similar pattern is really a light machine gun or simply an assault rifle with a heavier barrel and bipod. After all, virtually all members of the RPK family lack a quick-change barrel and fire from a closed bolt. Therefore, such a weapon can only deliver limited sustained-fire capability. Guns of this type are called machine guns because they are put in a role of the machine gun, not because they incorporate all desirable MG or LMG features. Back in the era of semiautomatic and bolt-action battle rifles, such designs were simply called automatic rifles. Modern designations like the light support weapon (LSW) more accurately describe their role. There are other machine gun definitions, too. To the anti-gun media, every small arm is a machine gun or assault weapon. Remarkably, the average sportsman buys into this errant terminology, as long as his side-by-side shotgun or pre-64 Winchester is not criticized by the media.

From a technical viewpoint, the RPK is pretty much an AKM fitted with a longer and heavier barrel and bipod. Yet some of it’s details are in fact borrowed from the AK-47 and RPD. Most RPK parts and components are interchangeable with the AKM assault rifles. Interchangeability simplifies both production and usage. This is likely the main reason why the belt-fed RPD was not replaced by another belt-fed design, but rather by a magazine-fed pseudo-machine gun, the RPK. Fielding a light machine gun very similar to an assault rifle simplifies the training of infantrymen as well as armorers, which is a particular advantage if it is employed by an army based on large reserves. This is the real genius behind the design of the Ruchnoy Pulemet Kalashnikova.

While the first RPK prototypes were built on AK-47 machined receivers, production models have stamped receivers. The receiver sub-components are stamped from sheet steel and assembled by spot welding. The barrel extension, which is machined from solid steel, is mated to the receiver by rivets. The most visible difference between the RPK and the AKM receiver is the RPK’s more massive barrel extension, which requires an enlarged frontal section of the receiver. The difference is clearly visible. The RPK’s receiver cover is similar to the AK-47 without the reinforcing ribs typical of the AKM.

The RPK’s breech block and gas system are identical to the AKM. The AK-type action is neither ammunition nor moisture sensitive and will provide reliable functioning under the most adverse conditions. Like its assault rifle counterpart, the RPK fires from a closed bolt, which is not the best method for weapons shooting continuous full-auto fire. Prolonged firing can heat the chamber to the point that cook-offs can occur, and the barrel rifling can be damaged by sustained firing.

The RPK does have a longer and heavier barrel than standard AK-47 or AKM assault rifles, which does improve heat dissipation to some degree. Barrel length is 23.3 inches (59.1 cm). The bore has four grooves with a right hand twist of 1 turn in 9.25 inches (21.0 cm). Like most military small arms of Warsaw Pact origin, the bore and chamber are chrome lined. Chrome lining provides better durability and corrosion resistance against powder and primer residues. Many people seem to have the wrong idea about wear resistance. It doesn’t mean that the bore will better resist wear from friction generated by steel-jacketed bullets. A different process is at work. Steel-jacketed bullets have a poor ability to conform to rifling and thus seal the combustion gases behind the projectile. Chrome is not as reactive as steel, so chrome plating is eroded less by the blow-by of hot combustion gases.

The RPK is poorly suited to the machine gun role, where long bursts or sustained firing are required. For that purpose, the barrel is too light and has no proper cooling system. Furthermore, the RPK barrel is not a quick-change design; instead, the barrel mounts permanently on the barrel extension by means of threads like the AKM barrel. However, at least one RPK variant—the Yugoslavian M65B—features a quick-change barrel.

Like the AK-47 and AKM assault rifles, the RPK muzzle has a left-handed metric M14x1 thread. It was originally intended for mounting a blank-firing adapter, but the threads have been subsequently used to accept various grenade launchers and sound suppressors. There is no compensator after the AKM fashion, but threads are protected with an AK-type nut. Fortunately, the RPK has no bayonet lug, unlike most other Soviet small arms including sniper rifles.

The RPK has a selective fire trigger mechanism similar to the AKM. It has a single trigger sear (instead of twin trigger sears used with the AK-47) and a rate reducer which delays backward movement of the hammer. However, the value of the rate reducer is doubtful. Both the AKM with rate reducer and the AK-47 without a rate reducer produce an equal rate of fire: 600 rpm. Because its longer barrel increases the amount and pressure of gas available to piston, the RPK has a slightly higher rate of fire: 660 rpm. Bear in mind, however, that these rates of fire are theoretical and depend greatly on ammunition.

The Soviet-made RPKs usually have furniture made from laminated wood. The fore-end has no longitudinal swells typical to the AKM, but otherwise the fore-end as well as the hand guard and pistol grip are patterned after Kalashnikov assault rifles. RPD stocks are made from various materials, and different shapes can be encountered. The sling swivels are mounted on the left side of the gun, and they accept an AK-type sling with a leather loop on one end and a metal hook on the other.

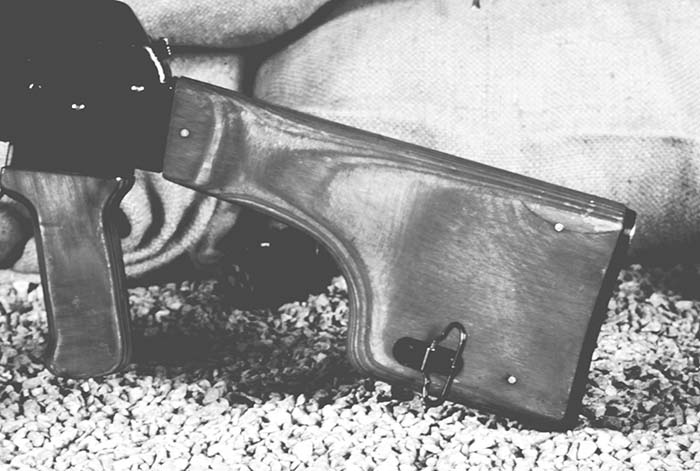

The shape of the butt stock reveals that the RPK should be fired from a bipod rest. The butt stock is patterned after the RPD, and it allows a support hand to grasp underneath the stock. This style of marksmanship could be referred to as “European,” while the practice of grasping the top of the stock with the nonfiring hand could be termed the “American” style of firing an LMG. Like most other small arms produced in the Eastern Bloc, the RPK has a remarkably short length of pull. The distance from the trigger to the butt plate is only 12 inches (30.0 cm). The short butt stocks are well suited for operators of somewhat smaller stature than the average American or operators wearing heavy winter clothing.

The Russian-made RPKS features a side-folding butt stock made from laminated wood and patterned after standard-issue RPK fixed stock. Yugoslavian variants have the same MP38/MP40-style stock folding underneath the receiver as used with AK-47 and AKM rifles.

Like most AKM rifles of Soviet and other Eastern European origin, the RPK usually features a painted black finish. However, blued and parkerized (manganese phosphate) guns can also be encountered.

The cleaning rod is located beneath the barrel. Other cleaning gear and a general purpose tool is carried in a stamped steel capsule placed in a compartment located in the butt stock.

The RPK bipod appears to be a simplified variation of the RPD bipod. It is mounted permanently near the muzzle. This arrangement provides maximum accuracy when engaging a stationary target but inhibits the gunner’s ability to traverse for engaging moving targets. The bipod’s hinge and mounting piece are machined from solid steel, and its legs are stamped from sheet steel. The bipod does not feature a provision for height adjustment. Despite its simple design, the bipod is rugged. Finally, there is no provision to fasten the weapon to other mounts.

All 7.62x39mm Kalashnikov magazines are interchangeable. The magazines especially designed for the RPK are a 40-round curved box magazine and a 75-round drum.

The 40-round magazine is similar to a standard issue 30-round staggered row box magazine, but it is longer and slightly more curved. While the longer magazine provides an additional 10 rounds, it seriously handicaps the maneuverability of the whole system. A 40-rounder works fine at the shooting range, but in rough terrain, the long magazine can interfere with firing the weapon from the bipod. In the field, it is much better to use a standard 30-round magazine or a 75-round drum.

The Soviet-made drum is completely different from the more frequently distributed Chinese design. The Soviet drum has no openable back cover, but it is loaded with loose rounds (or with a clip guide and stripper clips, if there is one available) from the top. The Soviet-made 75-round drum magazine is reliable, and it provides a lower profile than a 30-round magazine.

The Soviet RPK’s front sight is similar to the AK-47 or AKM rifles; it is a rectangular post with protective ears, not a hood as used with Chinese variations. A tangent-type rear sight has a U-shaped notch. In addition to its basic Kalashnikov design, the RPK rear sight is fully adjustable for both windage and elevation. The range scale is optimistically graduated to 1,000 meters. However, due to physical limitations and moderate external ballistics, the RPK’s effective range is no more than 400 meters.

Some RPKs have a rail-type scope mounting bracket on the left of the receiver. It is presumably intended for mounting an infrared or passive night sight, but not an ordinary rifle scope. There is no specific nightscope intended for the RPK. But according to the new Russian classification method, all current-issue small arms have an “N” suffix in their names if they have scope-mounting capability. For example, the scope-fitted (either 4 power 1P29 scope or passive night sight) 5.45x39mm RPK-74 is called as the RPK-74N.

Handling and disassembly procedures for the RPK follow the familiar Kalashnikov pattern. If you can handle and fire any AK-47 or AKM variant, you can fire the RPK. There are thousands and thousands of people who can’t read or write, but are nevertheless experts at handling and firing the Kalashnikov family of weapons.

The RPK in all its guises is the most widely distributed—but certainly not the best—LMG available in the world today. It is too light to provide good controllability for full-auto firing, and it’s closed bolt operation limits it’s ability to deliver sustained fire. On the other hand, the RPK is light and maneuverable, so it can be easily carried in difficult terrain. Fitted with a full 40-round magazine, the RPK weighs just 13.4 pounds (6.1 kg). The RPK’s similarity to the AK-47 and AKM facilitates the training of troops who must use and maintain these weapons. This similarity also lowers the cost of production, enabling the fielding of this LMG in greater numbers. While the RPK may not have the quality of the RPD it replaced, the deployment of the RPK brings to mind Stalin’s comment to Churchill that “quantity has its own quality.” Clearly, deployment of the RPK and its variants remains quite logical from a certain point of view. Nevertheless, perhaps the Ruchnoy Pulemet Kalashnikova should be viewed as an assault rifle on steroids rather than as a true light machine gun.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V1N3 (December 1997) |